Aside from the special counsel investigation into alleged Russian intrusions into the 2016 election, the really big deal in Washington now is the late-year push to enact a sweeping revision of federal taxes. The Republican initiative is the latest act in a public-policy drama stretching back over four decades.

North Carolina, of course, has had its own revise-and-cut dynamic. Instead of an omnibus tax bill as proposed in Congress, state Republican legislators have enacted major changes — cutting the corporate income tax, adopting a flat-rate income tax, and extending the sales tax to a few services — in stages since they gained a General Assembly majority in the 2010 elections.

Of course, the state’s education systems have a critical stake in how the tax debate plays out in 2018 and 2020. Schools, colleges, and universities contribute to the state’s economic advancement, and they draw sustenance from the state’s vitality and growth. In both Washington and Raleigh, tax-cut advocates insist that lowering rates and reducing what taxpayers owe in “dues’’ for governance will stimulate robust economic growth and thus provide sufficient revenues.

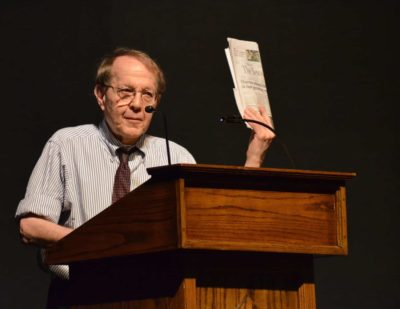

In a recent analysis in The Washington Post, Bruce Bartlett, a prolific writer of books on U.S. history, policy and taxes who served in the administrations of GOP Presidents Ronald Reagan and George H.W. Bush, directly challenges “the Republican tax myth.” He challenges it from his own experience in helping to write the 1981 Reagan tax-cut legislation.

That tax package, he writes, had a positive effect, but the prosperity of the 1980s was, in fact, less potent than the economic expansion of the following decade when Democratic President Bill Clinton proposed, and GOP lawmakers opposed, a tax increase in 1993. The 1990s, Bartlett reports, “was the most prosperous decade in recent memory.”

“I’m not sure how many Republicans even know anymore that Reagan raised taxes several times after 1981,” says Bartlett. And yet, since 1981, he writes, “tax cuts became the GOP’s go-to solution for nearly every economic problem. Extravagant claims are made for any proposed tax cut.”

Of course, Bartlett focused on federal taxes, not state taxes. Is it possible that cutting state taxes could give North Carolina a stronger economic kick than a reduction in federal taxes? There is an important difference: Congress can reduce taxes and still sustain or increase spending because it does not have to balance the budget. State government operates under a balanced-budget mandate, thus the legislature has to restrain spending on education, law enforcement, health care, and other services to meet available revenues.

Two recent analyses of North Carolina’s economic conditions offer evidence of the state’s recovery from the 2008-09 recession, but not much evidence that tax cuts themselves have created a widespread economic surge.

In his October “economic outlook’’ report, N.C. State University Professor Michael L. Walden reports that North Carolina has been on an “upward trend’’ in gross domestic product since 2010. Walden projects that North Carolina’s GDP will grow by 2 percent in 2017 and 2018, matching the national rate.

The state’s job-growth rate has exceeded the national rate for six of the past seven years, Walden reports, but job growth has been uneven, concentrated largely in the Charlotte and Raleigh metro areas. The two areas accounted for nearly two-thirds of state job growth since 2009. While the unemployment rate has plummeted, Walden says, the broader measure that includes people who have dropped out of the labor market shows more than 9 percent of potential workers are unemployed.

“Economic challenges continue,” Walden concludes, “with uneven growth across the state, the hollowing-out of the labor force, slow improvement in wages, and labor productivity gains that lag national gains.”

Meanwhile, in its just-released 2017 State New Economy Index, the Washington-based Information Technology and Innovation Foundation ranks North Carolina 22nd among the states. The rankings are based on 25 indicators in such categories as innovation capacity, knowledge jobs, and economic dynamism.

In addition, the foundation offers an analysis of states’ tax and investment patterns. It organized the states into four categories: high tax/high investment, high tax/low investment, low tax/high investment, low-tax/low investment. North Carolina placed in the low tax/low investment category.

That category includes, says the ITIF report, “traditional southern or southwestern states that have remained committed to the model of low costs, including Georgia, North Carolina, Oklahoma, Tennessee, Texas, and Virginia. All six of those states have made some attempts at more robust investments, including in higher education and technology-based economic development, but they still rank below average on investment, in part because some, such as Georgia and North Carolina, have cut back in recent years.”

In Washington, a huge debate has broken out over the tax-revision plan, informed by credible studies of the effects and consequences from both government and independent analysts. As North Carolina moves into the next round of contention over taxes and state priorities in 2018, its debate needs to be informed not by “myth’’ but by informed, independent assessment of the consequences.