On Aug. 21, leaders in education, nonprofit, government, and business sectors gathered at the NC Chamber’s annual education and workforce conference.

A month earlier, North Carolina was named the top state for business by CNBC for the third time in the last four years.

In response, the conference encouraged sector leaders to discuss North Carolina’s economic growth, technology’s hand in rapidly changing the state’s labor market needs, and their own opportunities to coordinate strategies that will prepare a confident future workforce.

![]() Sign up for the EdDaily to start each weekday with the top education news.

Sign up for the EdDaily to start each weekday with the top education news.

Changes in technology, including the rise of generative artificial intelligence (AI), were a focal point during the conference.

Stuart Andreason, executive director of programs at the Burning Glass Institute, explained in his keynote presentation how technology, especially AI, is altering the kinds of skills people need to have at their jobs and the types of jobs available.

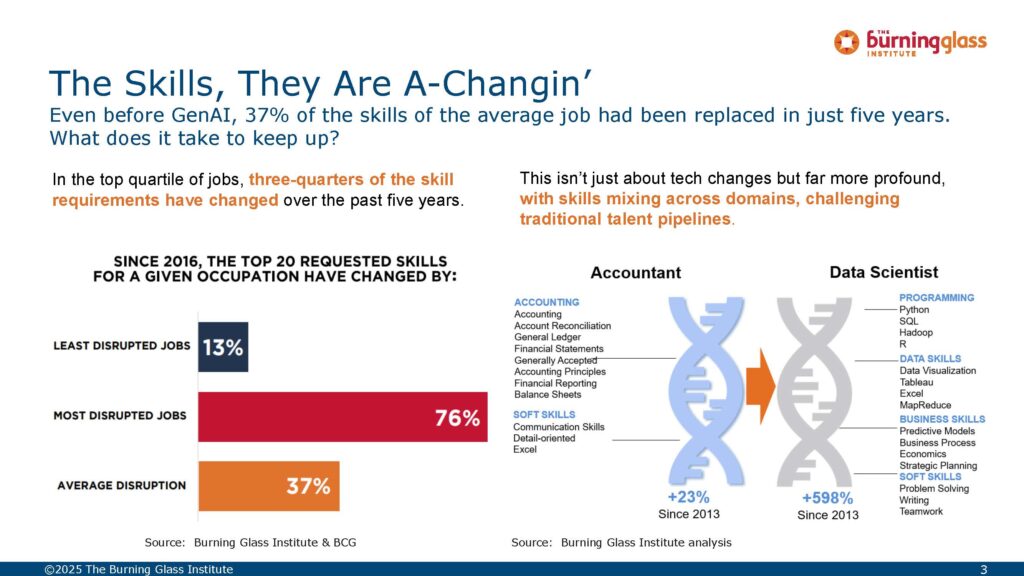

A 2022 analysis from the Burning Glass Institute looked at over 200 million job advertisements to see how they’ve changed over time. The report found that in the most disrupted jobs, technology has changed 76% of workers’ skills. For an average job, the same measure is 37%.

Andreason explained that this shift reflects an evolution of jobs’ DNA and, therefore, how leaders should prepare people for these jobs.

“For the educators, people in workforce training in the room, let’s all think about whether we’re being as flexible as we need to be. Have we adapted our curriculums by 37%, or 76%, as we think about what these jobs look like?” Andreason asked.

The conference continued last year’s discussion on AI, as Andreason highlighted a few ways AI is accelerating changes in education and the workforce.

For one, AI is creating challenges for people entering the labor force for the first time. As AI replaces many entry-level positions, the demand for people with on-the-job experience has increased, creating a tough job market for those newly entering.

Another AI growing pain is in its implementation. Businesses and industries have to figure out where it makes the most sense to use AI, and this calculation changes the kinds of AI-related skills future employees should focus on developing.

Andreason’s recommendation in light of these transformations is for communities to approach workforce development with the end in mind. Close relationships between educators and employers, who Andreason described as the “end-users” of students’ education, is one approach.

“As we think about what it means to enroll a student in education, let’s also think about enrolling them in a job,” he said.

Enrolling students in jobs is the driving force of what Executive Director Crystal Folger-Hawks does at Surry-Yadkin Works. The work-based learning program is a cross-sector partnership between four school districts, Surry Community College, and employers across two counties to train local K-12 school students in the skills they need to succeed in their local labor market.

An example of educator-employer relationships, Folger-Hawks meets with the presidents, CEOs, and HR directors of local businesses to identify the types of industry skills needed from today’s students.

In addition to technical skills, she hears that businesses would like to see students develop interpersonal soft skills, or “essential skills,” as they are called at Surry-Yadkin Works. The program helps students polish these abilities through activities like public speaking practice and networking with potential employers.

“If you’re not uncomfortable in our sessions, then we’re probably not doing a very good job with you. Because we make them go to lunch with strangers, we make them talk to everyone — everyone,” said Folger-Hawks.

The goal of the programming is for students to enter the next phase of their life with confidence.

This theme underscored the K-12 panelists’ discussion more broadly, as panelists spoke to the fact that workforce development, at its core, is about preparing people to secure jobs that then provide them the stability to be the best versions of themselves.

“What we’re also training them to do is to be confident, to be fair-minded community leaders. That’s what I want folks to take away from this,” said Ian Brown, vice president and chief employee experience officer at Duke University Health System. “These are humans that we’re actually training to become amazing citizens of our communities. We want them to take great jobs, but we also want them to be great humans out there as well.”

Programs like Surry-Yadkin Works exemplify how businesses and schools can work together to focus on their geography’s unique and changing workforce needs while also mentoring people toward economic independence.

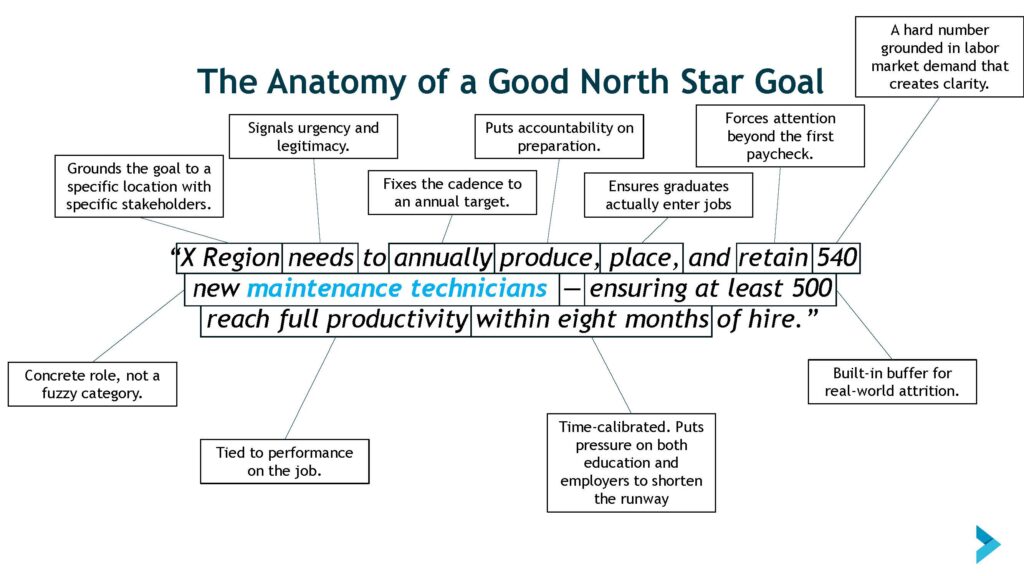

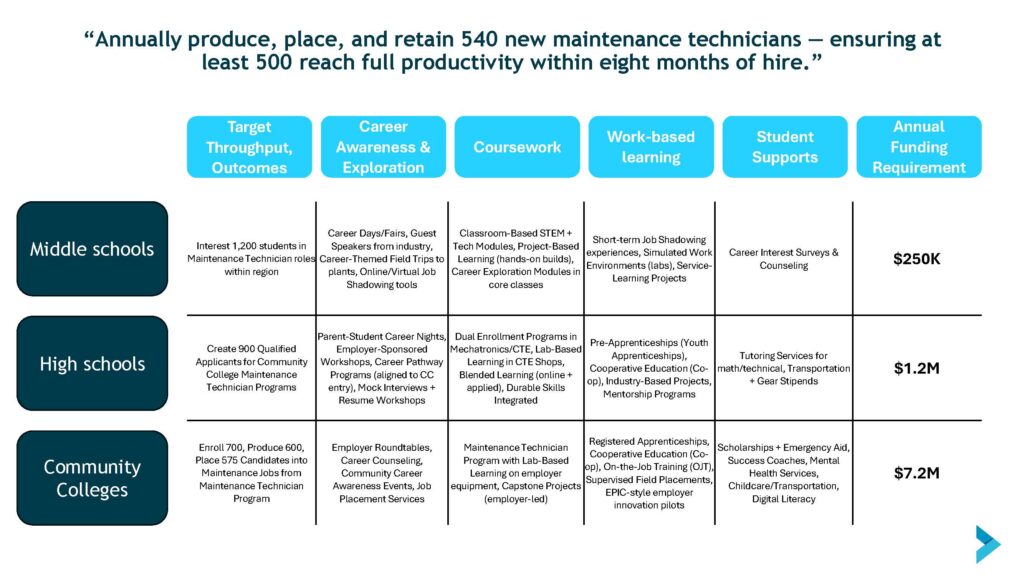

These partnerships are the kind Vincent Ginski, director of workforce competitiveness at the NC Chamber Foundation, sees as part of a potential solution to what he diagnosed as “an absence of an underlying framework that allows us to turn fragmented programs into coordinated pipelines capable of hitting a clear north star target.”

Instead, he said, leaders should develop a “North Star Goal” that is concrete, time-bound, risk-calibrated, shared between partners, and legitimatized. This kind of coordinated goal enables schools and community colleges to map out their unique contributions, and business leaders can clearly see where their contributions, like donations and mentorship hours, fit into the talent pipeline.

“That’s what infrastructure does. It doesn’t just coordinate effort, but allows us to transform the employer’s experience,” said Ginski.

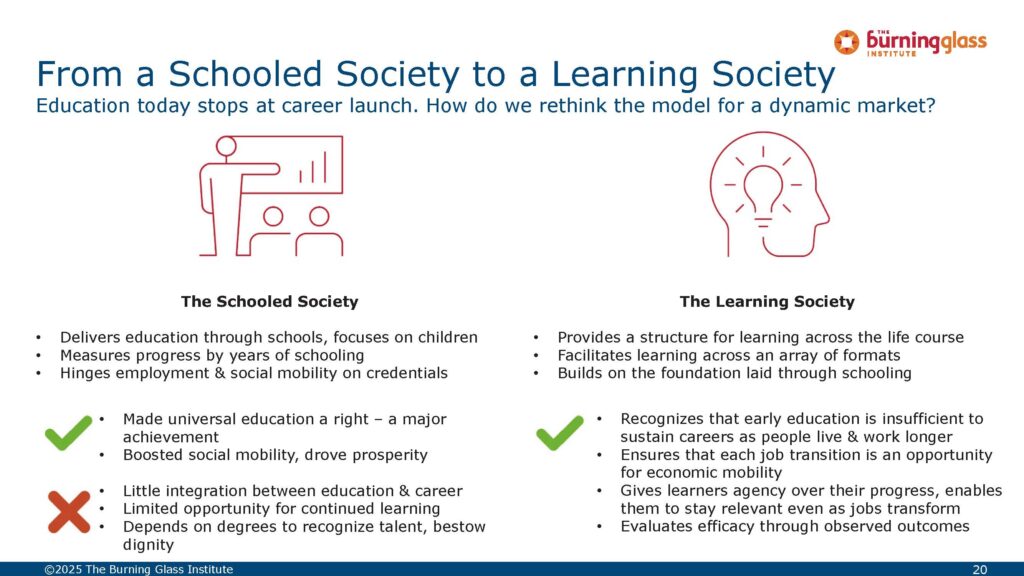

Surry-Yadkin Works is also the kind of program that models Andreason’s argument for a transition from a “schooled society” to a “learning society,” or one that views workforce development as a life-long endeavor rather than one that ends with a student’s formal education.

Higher education panelists also spoke to the importance of work-based learning experiences while emphasizing the need for higher education institutions to focus on programs with high return on investment for students and communities.

Kelly McManus, vice president of higher education at Arnold Ventures, stressed the need to focus on quality of programs rather than quantity. She highlighted apprenticeships within bachelor degree programs as a promising model she’s seen most commonly used in teaching that has been spreading to other degrees and fields.

“You need to look at the long-term data. You need to look at outcomes. How are people doing?” McManus said. “…Because what you don’t want to do is encourage people down a path that isn’t actually going to pay off for them, that is not good ROI for the student or for the state.”

Mary Varghese, UNC System senior associate vice president of strategy and policy, also emphasized the value of a degree from one of the UNC system’s 16 universities, referencing a recent analysis commissioned by the General Assembly that found a positive return on investment for 93% of the system’s undergraduate and graduate degree programs.

The opportunity, she said, is increasing lifetime earnings premiums by aligning programs with employers and making sure students develop technical skills within their degree field. Varghese pointed to UNC Charlotte’s experiential learning dashboard as an example for how data can spark conversations and strategies for specific programs and industries.

As Jim Hansen, regional president of PNC Bank, reminded the audience, NC’s booming population and economy is a moment of opportunity.

“There’s more people, that’s more workforce that we’re going to have, that we need to make sure is employed, successful, investing in our communities, in our economy, and making a difference so they can feed their families and live the life we want them to live as great North Carolinians,” Hansen said. “So the ask of this room is don’t sit back, make connection.”

Editor’s note: Dr. Monique Perry-Graves is on EdNC’s board of directors, and Arnold Ventures supports the work of EdNC.

Recommended reading