Editor’s note: This article is part of EdNC’s playbook on Hurricane Helene. Other articles in the playbook are available here.

On Feb. 24, 2025, five months after Hurricane Helene hit, EdNC published an article on the ongoing role of philanthropy in western North Carolina (WNC).

“There is a spell after an economic or natural disaster hits,” reads the article, “where especially in small rural communities, the leaders are already overworked and under-resourced, all of which makes the initial crisis period until state and federal resources start flowing really critical but also unreasonably stressful.”

Supporting leaders after a crisis is critical to both the short- and long-term recovery of communities and the institutions that serve them.

After Helene struck in late September 2024, leaders of schools, nonprofits, and small businesses were actively working to confirm the safety of their employees and community members, visiting school and office buildings to assess damage and developing strategies to meet the needs of the people they serve — all with limited access to roads, cell reception, and internet.

In the days and weeks following a disaster, education leaders balance active damage assessment and service provision with an eye towards reopening, and they need money to make that happen.

Funding and reimbursement opportunities begin to arise from federal sources, like the U.S. Department of Education and FEMA, to state sources, like the NC Disaster Relief Fund, to local sources, like the United Way and community foundations. Evaluating the array of opportunities, much less finding the time (or internet access) to apply for them, becomes an opportunity cost for local leaders — should they spend time now in active recovery or try to secure funding for one month down the road?

At the same time, philanthropy stepped up and leaned in after Hurricane Helene. Dogwood Health Trust (DHT), which serves 18 counties in the western part of our state, announced $30 million in initial relief funding on Oct. 4, 2024, including a lead grant of $10 million to an Emergency and Disaster Response Fund at the Community Foundation of Western North Carolina (CFWNC).

By Oct. 7, just over a week since Helene hit, CFWNC was making its first grants, going on to deploy $39.6 million through more than 525 grants.

Joined by other foundations from around the state, philanthropy effectively served as a first responder for financial support.

Philanthropic, state, and, eventually, federal investments provided critical funding to support recovery, but the number and complexity of these opportunities also created challenges for those navigating them.

Here are four lessons learned on the role of philanthropy in disaster relief and recovery.

1. A large, place-based foundation can quickly deploy funds in its region, allowing other funders to focus on other geographic areas in need

Natural disasters don’t follow human-created boundaries like county lines or a philanthropy’s area of service. However, having a philanthropy that quickly deploys funding to even some in the impacted area is important in both relief and recovery.

Western North Carolina is home to Dogwood Health Trust, which has an 18-county service area that includes the majority — but not all — of the counties impacted by Helene. The size and scope of DHT’s giving far exceeded that of typical philanthropic giving post-disaster.

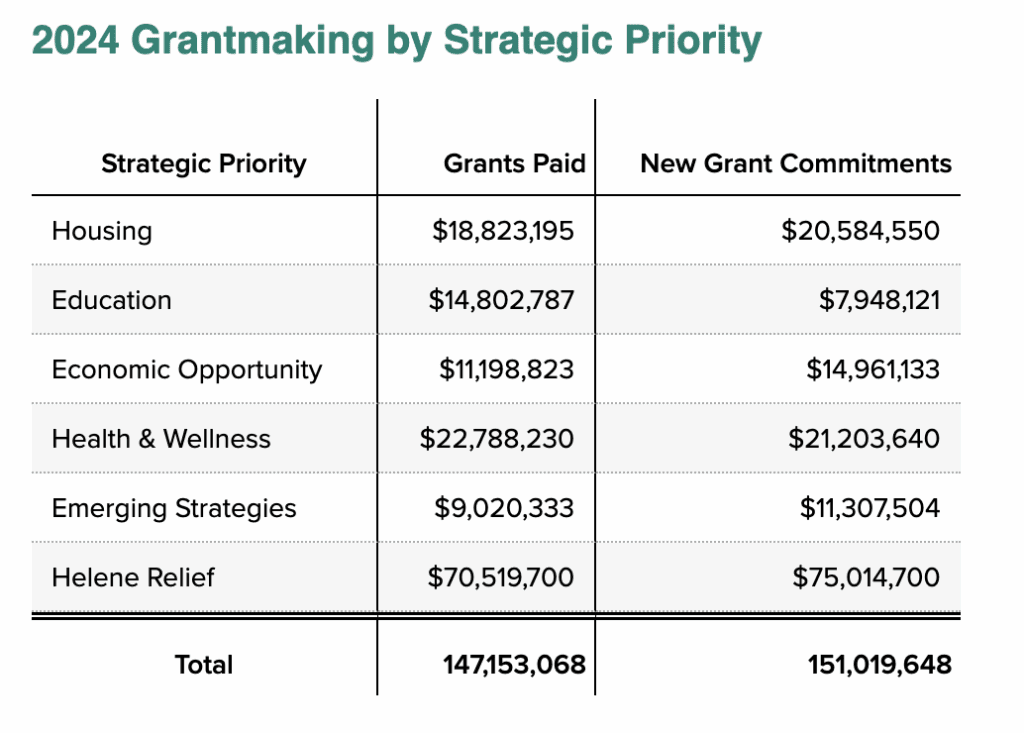

Of the trust’s $151 million in grants awarded in 2024, $75 million (or 49.67%) went to Helene relief. For context, according to the Center for Disaster Philanthropy’s 2024 report on philanthropic giving to disaster relief and recovery, “of the $126.7 billion given by private and community foundations, corporations, and public charities, $1.7 billion in total (or 1.4%) went to disasters in 2022.”

While these grants only went to organizations within the foundation’s geographic focus — meaning impacted organizations in counties like Ashe or Wilkes or Watauga were not eligible for these funds — the fact that the region is home to a foundation with $2 billion in assets (the third largest foundation in the state) is important.

While some counties couldn’t benefit from DHT funding, having more than $75 million in philanthropic dollars available to the majority of impacted counties freed up other resources that could go to organizations outside the regional foundation’s geographic focus.

According to this 2023 dashboard from nonprofit information hub Candid, the only other area of North Carolina that has a regional foundation with assets above the billion dollar threshold is Charlotte. This means the majority of the state is not served by a regional foundation that can deploy the kind of funding that made a big difference for those impacted by Helene.

Read more of EdNC’s Hurricane Helene Playbook

2. More funding is a good thing, but evaluating opportunities is time consuming

As noted above, when Helene hit, philanthropy stepped up — both in their giving and in opportunities for people to donate to trusted sources in support of those impacted by the storm.

The mix of philanthropic support, as well as anticipated federal and state funds, led to a list of potential funding sources that leaders had to analyze and consider.

As mentioned, with funding from DHT, the CFWNC launched the Emergency and Disaster Response Fund, which began deploying funds to nonprofits and public agencies on Oct. 7, 2024.

In the days following the disaster, then Gov. Roy Cooper encouraged people to donate to the NC Disaster Relief Fund through which “eligible non-profits could seek grants and reimbursement of up to $10,000 from the NC Disaster Relief Fund for efforts to meet immediate storm recovery needs via the United Way of North Carolina.” According to their website, applicants needed a “valid solicitation license with the Secretary of State’s office, a letter waiving the need for a license, or to be in the process of applying.”

The United Way of North Carolina also launched its own, separate fund. The UW Helps NC Fund “allow(s) United Ways in the affected areas to respond to our local agencies’ immediate requests and to meet needs.”

The North Carolina Community Foundation has its own disaster fund, too. The foundation’s NC Disaster Recovery Fund was established in 1999 to support “long-term disaster relief and recovery.” Once the disaster response moved to recovery, the balance of funds raised through the NC Disaster Relief Fund moved to the North Carolina Community Foundation’s NC Disaster Recovery Fund. Unlike the NC Disaster Relief Fund, which was only available to eligible nonprofits, the recovery fund is available to “eligible charitable organizations and government entities in North Carolina communities impacted by disaster.”

According to the foundation’s website, “(a)s of Sept. 30, 2025, nearly $12 million has been allocated to support long-term recovery in western North Carolina. Over $32.5 million has been contributed and grantmaking is ongoing.”

Small businesses could receive funding through the Western North Carolina Small Business Initiative (funded by DHT) or the WNC Strong: Helene Business Recovery Fund.

The Golden LEAF Foundation, the John M. Belk Endowment, The Leon Levine Foundation, the Z. Smith Reynolds Foundation, Blue Cross Blue Shield of North Carolina and the Blue Cross and Blue Shield of North Carolina Foundation, and the SECU Foundation also provided quick support.

Early on, there was an attempt to catalog these funding opportunities. Innovative Funding Partners released this grant resource guide on Oct. 8, 2024. The Governor’s Recovery Office for Western North Carolina (GROW NC) was established in early 2025. GROW NC’s website houses a list of current funding opportunities and deadlines.

EdNC is working to create a comprehensive list of Helene recovery funding opportunities. If we missed something, please email us at mrash at ednc.org.

Read more about Helene recovery

The magnitude of the storm also drew the attention of funders outside of North Carolina. The Hearst Foundations awarded $1 million in disaster relief in the aftermath of Hurricanes Helene and Milton in fall 2024. Sarah Mishurov, the director of strategy and operations with Hearst who lives in London, sent her kids to camp in summer 2025 and drove around WNC to meet in person with those that needed grant support.

Soon after the disaster, FEMA authorized a representative from the U.S. Department of Education’s Project SERV to be on the ground in WNC as a primary point of contact for schools in the disaster area. Project SERV (School Emergency Response to Violence) “funds short-term education-related services for local educational agencies (LEAs) and institutions of higher education (IHEs) to help them recover from a violent or traumatic event in which the learning environment has been disrupted.”

The Concert for Carolina, headlined by Eric Church and Luke Combs, raised $24.5 million that Church and Combs split among organizations they supported. Church funded his nonprofit Chief Cares, and Combs funded Manna Food Bank, Second Harvest Food Bank of Northwest North Carolina, Samaritan’s Purse, and Eblen Charities.

While earlier relief bills were passed, in March 2025, the legislature passed and the governor signed into law the Disaster Recovery Act of 2025. Part 1, which provided $524 million in aid, included funding for farmers, home reconstruction, infrastructure and roads, debris clean up, and learning recovery. Part 2 became law in June 2025 and provided $575 million, including $50 million “for repair and renovation of facilities in counties with a federal disaster declaration due to Hurricane Helene for local school administrative units and lab schools. These funds are for unmet needs not covered by insurance or available federal aid.”

Evaluating these funding opportunities takes time, and time is a limited resource in times of disaster. Leaders had to assess:

- If their organization was eligible for the funding as not all opportunities were open to public agencies or small businesses;

- Whether their anticipated expenses were allowable as some funders didn’t cover costs that would be covered by FEMA, and some funders could not cover costs that philanthropy might cover;

- When and how the funds would come in as some funders allowed grantees to use grants to reimburse expenses already incurred while others did not; and

- What the reporting requirements might be as some funders waived complex reporting, while others expected detailed financial and programmatic updates.

Accomplishing these “to-do” items is a challenge during the regular workday; it can be paralyzing during times of disaster, particularly for those entities with no experience with restricted or reimbursable grants.

![]() Sign up for the EdWeekly, a Friday roundup of the most important education news of the week.

Sign up for the EdWeekly, a Friday roundup of the most important education news of the week.

3. Public agencies with charitable entities can access (and deploy) more funding

Having a foundation can also help public agencies raise funds, as foundations can solicit tax deductible donations and grants from entities that restrict giving to charitable foundations.

For instance, neither the N.C. State Board of Education nor the N.C. Department of Public Instruction have a foundation, which limited the state’s ability to quickly raise additional funds for K-12 public schools while they were waiting for state funding to come in.

The state’s community college system does have a foundation, and they were able to raise funds from philanthropy, corporations, and individuals that allowed them to distribute $560,000 “across four rounds of funding to affected community colleges, helping them rebuild and provide critical resources to students and staff.”

4. Organizations need quick access to flexible funds in times of disaster, and streamlined applications can help

Once leaders evaluated funding opportunities, they had to find time — and, for some, literal internet bandwidth — to apply. Many organizations needed access to quick, flexible funding.

For example, schools could not reopen without access to portable toilets and handwashing stations, which cost money. One district received an estimate for $214,245 for seven days of rental — an amount that could wipe out most organizations’ fund balances. FEMA ended up arranging for and covering the costs of the rental.

Both the Community Foundation of Western North Carolina’s Emergency and Disaster Response Fund and the U.S. Department of Education’s Project SERV provided accessible and streamlined applications that demonstrated an understanding of the pressures leaders face when navigating a disaster.

In addition to deploying Emergency and Disaster Response grants quickly, CFWNC did four things that made a big difference:

- Including public agencies as eligible recipients (unlike the NC Disaster Relief Fund)

- Providing grant writing assistance

- Giving flexibility to use funds to meet immediate disaster response needs

- Distributing funds quickly, often within one week of award notification

As mentioned, to date, the foundation has distributed $39.6 million through more than 525 Emergency and Disaster Response Fund grants.

The inclusion of public agencies meant school districts could apply for funding, and an Oct. 12, 2024 checklist from the N.C. Department of Public Instruction provided a ready-made framework for the description of immediate response needs. This checklist allowed EdNC to draft this framing for districts to use when requesting funds:

In response to the guidance distributed by NC DPI on Friday, Oct. 12 to get students back to school each school in our system will be focused on the following:

- Ensuring the school properties are safe to return to,

- Supporting educators getting back to the classrooms,

- Paying for professional cleaning of the schools,

- Purchasing relief supplies for students and educators,

- Supplying security for added pick-up/drop-off locations for buses,

- Providing mental health services for students and educators,

- Arranging for food delivery/preparation,

- Procuring water and hand washing stations as needed, and

- Providing before and after school care.

The framing was the starting point for the template below, created by EdNC, that school districts could complete either electronically or over the phone. In just 48 hours, three districts submitted requests totaling $550,000 to the CFWNC.

Project SERV began in 2000 to provide immediate aid in the aftermath of a school shooting. In September 2001, SERV provided funding to the schools most affected by the September 11 terrorist attacks. Since that time, SERV has awarded funds to schools and institutions of higher education that have experienced:

- School shootings

- Suicide clusters

- Terrorism (response to 9/11, Washington, DC sniper incident, Virginia Tech)

- Major natural disasters (e.g. response to Hurricanes Harvey, Irma, and Maria)

- School bus accidents

- Student homicides (off campus)

- Hate crimes committed against students, faculty members, and/or staff

Two things set SERV apart from traditional federal funding: covering both past and prospective expenses to restore the learning environment, with the expectation of what FEMA would cover, and streamlining the application process and award management. The applications are designed for people and institutions navigating a disaster. There’s no portal, no SF-424A, no cover pages — just an initially “unburdensome” application process with a 4-5 page submission that addresses specific provided questions.

Similar to the CFWNC, this straightforward and audience-centered application approach allowed EdNC to develop a template (see below) that districts could quickly complete — some on their computers, and some working in-person with a member of the EdNC team — to submit to SERV for feedback.

In a matter of just a few weeks, EdNC supported four districts and one community college in submitting $1.93 million in requests to Project SERV. You can see all 2025 Project SERV recipients here.

These straightforward, flexible application and award processes got school districts the funding they needed to move forward with relief and recovery.

This approach is not unlike the Yield Giving/MacKenzie Scott giving model of providing large, unrestricted gifts to a vetted organization. According to the Center for Effective Philanthropy, “Scott’s very large, unrestricted gifts — with few to no restrictions on the time in which they must be spent — have transformed recipient organizations and influenced many of the communities these organizations serve.” The Center’s evaluation of recipient organizations found that “two years after grant receipt, organizations that received a grant from Scott have a median of twice as many months of operating expenses in cash reserves as comparable nonprofits.”

If one of the goals in supporting nonprofits and public agencies in times of disaster is the long-term recovery of institutions, then philanthropies should consider moving to both streamlined applications designed for those operating in disaster conditions and flexible funding designed for organizations that know best how to meet the needs of the people they serve.

Considerations for the future

- Is the expectation of philanthropy as a first responder for funding after a disaster reasonable and sustainable?

- Philanthropy doesn’t fund what will be covered by state and federal funding and vice versa. But in the early days of recovery, who will pay for what and the timing of the funding is often unknown. Those seeking funds are caught in the middle.

- What happens when there is a disaster in counties where there is no large foundation, such as DHT, or community foundation, such as CFWNC?

- Is there a way to better coordinate philanthropic support to address equity issues across the disaster region stemming from eligibility for particular grants due to funder restrictions, such as geographic restrictions?

- The more streamlined the applications, the more likely grantees will be able to submit for funding.

- Much like the health insurance industry has navigators to help those needing insurance, is there a way for there to be navigators to help grantees in crisis assess, triage, and submit grants?

- Should philanthropies consider always including public agencies as eligible for funding? If not, then do more public agencies need foundations or nonprofit affiliates?

Editor’s note: Dogwood Health Trust, Blue Cross and Blue Shield of North Carolina Foundation, John M. Belk Endowment, and Z. Smith Reynolds Foundation support the work of EdNC. EdNC’s CEO, Mebane Rash, serves on the Z. Smith Reynolds Foundation Board of Trustees.

Recommended reading