Share this story

- What does it take to create an organization from the ground up that successfully serves a population with generations of trauma, poverty, and mistrust? Patience, persistence, and "a willing heart."

- One challenge in rural North Carolina, and in our seven most western counties, is having institutions with resources understand what communities really need. How has HIGHTS stepped into those spaces successfully, and can it be replicated in other regions?

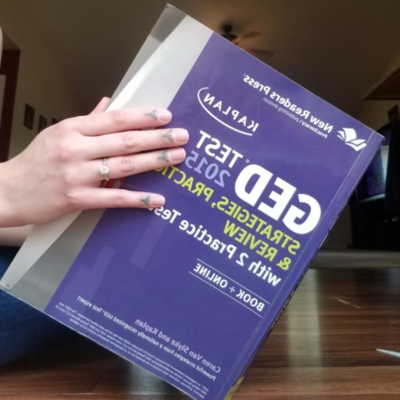

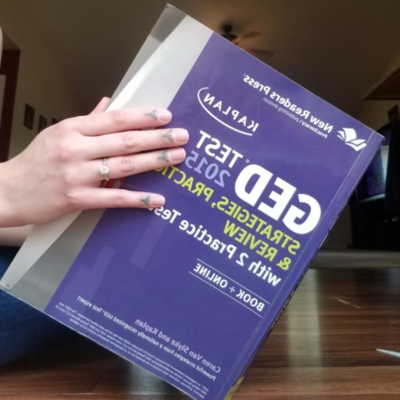

Friends of Heather Angel would lean over to show her a text message and wait for a response. She was learned in the way of body language, and could usually understand how she should react. Angel depended on others for car rides, because she had never gone to get a driver’s license. If there was a doctor’s appointment, she would have to rely on a family member to do her paperwork.

The smallest of daily interactions many take for granted would constantly remind Angel that she couldn’t read. At age 23, she found her way to Southwestern Community College to learn about the GED program. Angel was determined to change her future.

She went to night classes for two years before learning she could attend a day class, and that’s where things began to accelerate. She credits the educators at the school who put their time and energy in encouraging her at every hurdle. Halfway during her first year of day classes, she was introduced to the HIGHTS program.

HIGHTS stands for “Helping Inspire Gifts of Hope, Trust, and Service,” and the caseworker of the nonprofit said they could give her money for gas and child care, helping support her education journey.

Once she became a participant of the program, she also received a stipend as she increased her scores on reading and math assessments. The program’s funding rewards participants when they succeed.

The particular arm of HIGHTS that helped Angel falls within their workforce development program. The program is for students who have dropped out of high school and is funded totally by the federal Workforce Innovation and Opportunity Act (WIOA).

One element of the program is that while a participant is attending school, HIGHTS places them with a job for 6 to 12 weeks and pays the participant’s salary for the employer. HIGHTS also can pay for the five GED tests and offers a stipend when the participant receives their diploma.

Angel now has a job in health care as a certified nursing assistant, at the same employer HIGHTS secured placement from the start. She has worked there for two years, is on the way to being a certified medical technician, and received raises that exceeded her expectations.

Angel’s story is unique, but the need for support in North Carolina’s westernmost counties is not. HIGHTS has grown in service over the last 15 years, always in reflection of need.

What other wrap-around resources does HIGHTS provide, and is there a secret sauce that has allowed the program to keep expanding when others like it have struggled?

Origins of HIGHTS

“It’s all about relationships,” said Caroline Williamson, youth workforce and education development program director at HIGHTS. “It just comes back to that with our partners, with our participants. Marcus is brilliant with relationship, and so is Greta.”

Marcus and Greta Metcalf went to Western Carolina University. In 2004, they created HIGHTS as a volunteer organization working alongside Jackson County Psychological Services to provide youth adventure programming. In 2008, they established it as a nonprofit.

Now, Marcus serves as the executive director, and Greta, a licensed clinical mental health counselor and supervisor, is the organization’s clinical operations director.

In starting HIGHTS, they believed the population they were serving had never utilized the many natural resources in the area. With this in mind, the main focus was connecting youth to the outdoors. Activities included hiking, rafting, caving and more — utilizing the gifts of the region while participants build resiliency.

From the beginning, the organization focused on mental health.

“The further west you go,” Marcus said, “the harder it is to access resources.”

The counties HIGHTS serves are geographically isolated, and therefore often forgotten when it comes to state funding. Marcus continues: “The seven western counties have been generationally impoverished, and dealing with poverty and trauma, and neglected from all of the state funding that has been going out, forever and ever.”

After starting HIGHTS, the organization witnessed resource gaps in the community for kids and kept trying to step into the spaces of need.

“Eventually we became ‘experts’, (that’s) the word right? It’s like, we’ve stayed here long enough, to where we understood the need better than most anybody else around us.”

Marcus Metcalf, executive director of HIGHTS

From 2011 to 2022, HIGHTS added nearly 10 new programs, grouped under four branches, all in response to working with students and identifying new opportunties to help. Last year, HIGHTS was selected as a myFutureNC Local Educational Attainment Collaborative by ncIMPACT.

Relationships, relationships, relationships

With additional programs, came additional partnerships and larger reach.

At the beginning, HIGHTS only serviced kids from Jackson County. It now works within Jackson, Haywood, Macon, Swain, Graham, Clay, and Cherokee. These counties are also grouped together in the 30th Judicial Alliance, Region A in the Partnership for Children, and The United Methodist Church’s Smoky Mountain District.

Identifying other organizations that work with these particular counties allows HIGHTS to leverage resources and partnerships.

HIGHTS’s relationship with the juvenile justice system, for example, is paramount to their work with youth in the area. The partnership gives the organization a seven-county reach and access to special funding. Marcus said if a kid picks up any type of charge, they can connect to HIGHTS’s restorative justice programs.

Once a youth is referred to HIGHTS, they help identify services and connect with the student’s school to work together.

The school connection has created new resources for at-risk youth. Schools can refer students to HIGHTS if they get suspended. The program picks up students from home and transports them to skill-building or community service activities during the school day.

After-school programming is offered by way of HIGHTS’ Compass program and takes place in United Methodist Church buildings across the region. So far, three churches have opened their doors for this program. Compass gives students a place to go, and provides transportation, healthy meals, and social activity that benefits communities with dedicated service projects.

HIGHTS has 22 staff members and accepts volunteer help from the community. WCU is a huge partner, as the organization gets recreational therapy ambassadors and masters of social work interns to support programming.

Where are HIGHTS offices? In schools, community colleges, and United Methodist Church buildings. Those places have generational impact, and that isn’t lost on HIGHTS.

“We know that things like anchor institutions, like I talked about churches and other nonprofits and school systems, are going to outlast any of the people,” Rev. Julia Trantham Heckert, community engagement coordinator at HIGHTS, said, “so we want to make sure we have strong partnerships, so these services continue well into the future.”

HIGHTS lists over 30 partners on their website, but the amount of help continues to grow. Marcus said there have been a lot of “complicated dances” during the last 15 years: navigating what HIGHTS finds the community needs versus what institutions can provide, and matching it with funding opportunties.

“A lot of the work that I do is not super complicated, and it just take somebody with a willing heart and dedication and passion.”

Marcus Metcalf, executive director of HIGHTS

Trust is one of the key ingredients in HIGHTS’s stew of success. The challenge in rural North Carolina, and in these isolated areas, is integrating institutions with resources into the culture of the community.

Marcus and his team seem keen on learning from the people they serve. They understand there is an environment of distrust, and they keep showing up and offering the necessary support for vulnerable populations.

“I have had the opportunity to be at the circle for a long time”

Marcus Metcalf, executive director of HIGHTS

This allows a bigger picture perspective. The first, second, or third time he and HIGHTS have offered help to schools or students, they may not of heard him. But the fourth time they do. The organization’s persistence, patience, and wrap-around services have earned them a place at the table in Western North Carolina.