Share this story

- About 250 people from 70 N.C. counties gathered in Myrtle Beach, South Carolina, on Aug. 7-9 for the first convocation since 2019. The theme, “Gathering with Hope,” reminded attendees of what it looks like to be Christian leaders during challenging times.

- "The antidote to sin, or to separation, is connection, and there are many forms of connection. And so gatherers are in the business of connection, without oppression," Speaker Priya Parker said at the event.

|

|

Clergy across North Carolina met last week for the Duke Endowment’s Convocation on the Rural Church for the first time in four years – carrying the grief and weight of the pandemic, societal upheaval, and disaffiliation within the United Methodist Church (UMC).

Importantly, they also carried hope.

“By God’s mercy, we do not lose hope,” said Dr. Michael Brown during the convocation’s closing sermon. “Why? Because where you go today, you don’t go by yourself.”

About 250 people representing 70 North Carolina counties gathered in Myrtle Beach, South Carolina on Aug. 7-9 for the first convocation since 2019. The theme, “Gathering with Hope,” was meant to remind attendees of what it looks like to be Christian leaders during challenging times.

As United Methodist clergy have navigated disaffiliation, many have also tried to help their communities navigate and respond to the “twin pandemics” of COVID-19 and systemic racism.

Needless to say, clergy were more than ready for the opportunity afforded by the convocation to rest and rejuvenate.

“These are people who love and serve their communities every week, on purpose,” Dr. Kate Bowler, associate professor of American religious history at Duke University, said during the convocation’s opening plenary. “These are people who are changed by the last few years, and maybe they need a minute to think about this backdrop of loss and reinvention.”

Bowler, who is also a New York Times bestselling author and award-winning podcast host, was diagnosed with Stage IV cancer at age 35. Since then, she has wrestled with what it means to offer hope that is both beautiful and honest – frequently publishing blessings on her social media for people experiencing all kinds of hardship.

On Tuesday morning, she closed the plenary with one such blessing.

In your leading and in you serving, bless you.

In your pastoring and your gathering, bless you.

In every, ‘How’s this going to go?’ and ‘What if we?’ – bless you.

In all the ways that you pour out for others and facilitate communities of belonging and hope, bless you.

May this be a season marked by putting to rest what is no longer for you, and the coming alive of every good and beautiful thing.

Dr. Kate Bowler, associate professor of American religious history at Duke University

On gathering well

Ahead of the convocation, attendees received a copy of Priya Parker’s “The Art of Gathering: How We Meet and Why it Matters,” which offers strategies to transform how people gather together.

The first plenary featured a conversation between Bowler and Parker on the importance of gathering and belonging, particularly in the church.

“Gatherings are a temporary alternative world that we enter, we experience something, and we exit,” said Parker, who is also a a facilitator, strategic advisor, and executive producer and host of The New York Times podcast, Together Apart.

“Part of the beauty of that and part of the power of that is that we all get to create those worlds every day,” she said. “There are so many different ways to create belonging, and it doesn’t have to be to one identity, but in a diverse, multiracial, multi-ethnic, multi-religious society that that we are fighting for, part of the deep pleasure and ultimate responsibility is creating gatherings – creating worlds, creating contexts – in which people arrive and feel like, ‘Wow, my people are here.'”

It is both a deeply important and democratic skill to create such spaces, Parker said – where people can arrive how they are, and choose to stay.

This skill is especially relevant for N.C. Methodist clergy, Bowler said, who are typically appointed to churches by the UMC. The art of gathering, then, Bowler and Parker said, is important to combat loneliness in contexts where a pastor might be very different from their congregation.

“When we are lonely, when we feel disconnected from another, we behave in very different ways,” Parker said. “When we are lonely, when we feel that we don’t matter, when we feel that we are unconnected, when we feel different from one another – particularly in a multiracial society – this has incredibly devastating effects.”

So how does a leader attempt to gather well?

According to Parker, gathering well and creating belonging starts with seeing clearly what a community’s need is. This then helps you discover the specific purpose of every gathering.

Parker gave the example of a birthday party, which many people assume has an obvious purpose.

“If we pause and don’t think about the pointy hats or the birthday candles, and we pause and we ask, what is the need in my life right now as I turn 43, or 63, or 83,” Parker said. “Am I seeking a sense of adventure? Do I feel really bored but feel stuck in a rut? And then being able to identify that need.”

Under such a thought process, a birthday celebration could look like jumping into a lake with a small group of friends, or getting up early to watch fisherman at sunrise. The point, Parker said, is that thinking about the need behind an event transforms it into something more meaningful.

At the same time, a clear purpose also helps you make decisions about the event – where to host it, who to invite, and who to not.

“So often, so much of actually gathering well is need identification,” Parker said. “And then gathering and rallying others around that need and finding a form that fits.”

Parker gave other advice on gathering well, listed below.

- Accept that your needs will change, and adapt events in response.

- Be intentional about who you invite. “When you have a specific purpose, exclusion is not personal, it is purposeful,” Parker said.

- The size of a gathering really matters.

- Gathering involves both connection and boundary-setting.

- Don’t be afraid to “sunset” events that no longer serve your community.

“Sin is very simply separation – separation from God or the divine, and separation from one another,” Parker said. “And the antidote to sin, or to separation, is connection, and there are many forms of connection. And so gatherers are in the business of connection, without oppression.”

On the impact of the rural church

Rural churches are economic powerhouses for their communities, according to a recent report by Partners for Sacred Places, in partnership with the Duke Endowment and the UNC Charlotte Urban Institute.

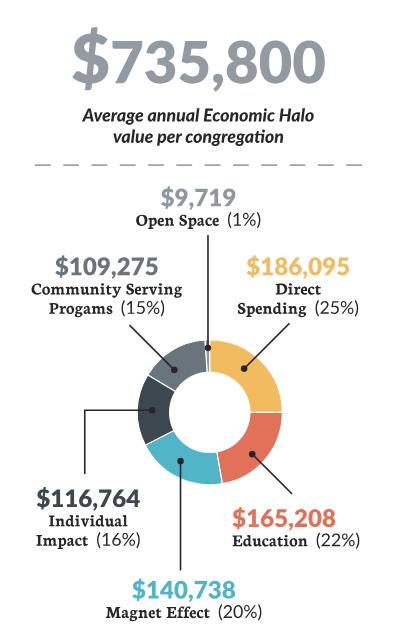

The report, “The Economic Halo Effect of Rural United Methodist Churches in North Carolina,” studied 87 rural UMC congregations over two years – ultimately finding that the churches generated $735,800 per year on average in local economic impact.

For the 1,283 total rural UMC churches in North Carolina at the time of the study, the economic impact was more than $944 million annually.

At last week’s convocation, Partners for Sacred Spaces hosted a workshop to explore the findings. The national nonprofit is “dedicated to sound stewardship and active community use of older sacred places across America” and all faith traditions.

“What’s exciting about the research we’re going to talk about today is it really helps tell a very different story about the value of our churches that most people have not yet heard,” said Partners for Sacred Places Director Bob Jaeger.

Notably, the report found that 72% of those benefiting from programs housed in UMC churches are not members of those congregations.

The report focused on six research areas:

- Direct spending – At 25% of the total, this category includes purchasing local goods and services, and employing local residents.

- Education and child care – At 22%, this category only represents child care centers in the N.C. sample. Thirteen of the 87 churches had child care centers (51%), serving an average of 51 children.

- Magnet effect – At 20% of the total, this category reflects visitors and volunteers churches attract to their region, who then spend money locally on hotels, food, and transportation.

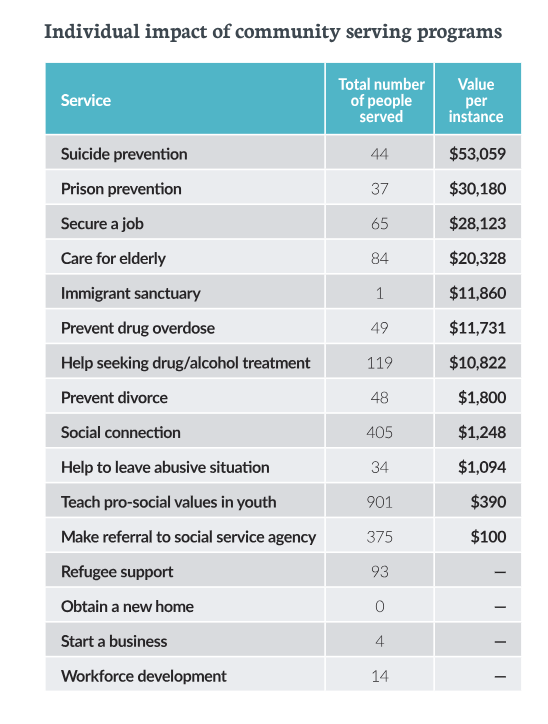

- Individual impact – At 16% of the total, this includes clergy or volunteer ministers who provide services like counseling or referrals to social agencies in one-on-one settings.

- Community serving programs – This category, 15% of the total, captures the many ways churches serve their communities – through sharing space, volunteering or hosting volunteers, providing financial aid to operate or support resource programs.

- Outdoor recreation space – This category, 1% of the total, includes the contribution of amenities like community playgrounds.

About 93% of the surveyed churches are predominately white. The sample included four predominantly Black congregations, one Latinx congregation, and one Native American (Lumbee) congregation.

The median size of the sampled churches was 110 members – with churches ranging from just five to 350 members.

Rachel Hildebrandt, the director of the National Fund for Sacred Places, said she was surprised by how high the numbers that came out of the study were.

“I thought the numbers would be lower, to be very honest,” she said. “I think this study really dispelled some myths for me personally and professionally, about how how valuable and important these kinds of congregations can be.”

Other workshops at the convocation included:

- Lament, Listen, and Reimagine: An Introduction to the Healing Circle Process, led by Dr. Nina Balmaceda and Rev. Dr. Yvette Pressley.

- Re-Discovering a Prayer Practice for Life as Clergy: The Daily Examen, led by Mark Shaw.

- Spiritual Resources That Help Us Endure, led by Rev. Dr. Michael Long.

- Preaching with Hope, led by Rev. Dr. Michael Brown.

- Church Gathering and Giving, led by Jim Holladay and Sean Mitchell.

The convocation also featured a 24/7 prayer room, designed by Laura Hamrick and Kristen Richardson-Frick, which was open to all hotel guests.

On ‘unimaginable, careful hope’

On the final morning of the convocation, Dr. Katherine Smith and Jessica Richie offered a plenary on hope, identifying need, and the theology of blessings.

“One of the things that is so marvelous about this gathering that I don’t often see in gatherings of pastors or especially academic gatherings, is that you’re not just trying to figure out how to be more holy,” said Smith, the associate dean for strategic initiatives at Duke Divinity School. “You’re figuring out how to be more human.”

Richie serves as the executive director of the Everything Happens Initiative at Duke University and the executive producer of the Everything Happens podcast, “which hosts wise, funny, and tender conversations between Dr. Bowler and guests about lives that don’t always work out.”

Smith asked Richie about the place of suffering in the team’s work.

“We have this wonderful team of people who receive notices all the time… (of) stories of unimaginable, careful hope in the midst of really impossible, oppressive, difficult situations,” Richie said. “…This what we’re charged with, is saying beautiful and true things in the midst of impossible situations.”

Such impossible situations are too big for us to handle alone, Dr. Alma Tinoco Ruiz said during the convocation’s opening message, “What Nurtures Our Hope.”

Tinoco Ruiz – assistant professor of the practice of homiletics and evangelism, and director of the Hispanic House of Studies at Duke Divinity – preached a message on the biblical story of Mark 4:35-41, when Jesus calms a storm while out at sea.

In the story, Jesus’ disciples wake him from his sleep on the boat asking, “Teacher, don’t you care if we drown?” According to the passage, Jesus then rebukes the wind and waves into calmness – next rebuking the disciples for their weak faith.

We too, are like the disciples, Tinoco Ruiz said. We also lament and cry out when we are drowning in our hardships and grief, and Jesus seems to be asleep.

And yet, Tinoco Ruiz said, we can lament to God because we believe God listens to us. As we lament, she said, we also find moments of hope.

“It gives me hope that Jesus, our resurrected God, does not tire anymore – he is not asleep anymore,” she said. “The good news is that today we can participate in God’s liberating, healing, and transforming mission in the world – to help each other get through the many storms we experience.”

Editor’s note: The Duke Endowment supports the work of EducationNC.

Behind the Story

This story is a part of EdNC’s faith work. If you’d like to share your faith story with us, reach out to hmcclellan@ednc.org.

Recommended reading