The Center for Racial Equity in Education (CREED) has recently released “E(race)ing Inequities” — an analysis of the state of racial equity in North Carolina public schools — along with a companion report, “Deep Rooted: A Brief History of Race and Education in North Carolina.” This work is led by James Ford, executive director of CREED, in partnership with the North Carolina Center for Public Policy Research. As part of this series, we are profiling figures across North Carolina who have experienced the crossroads of race and education first-hand.

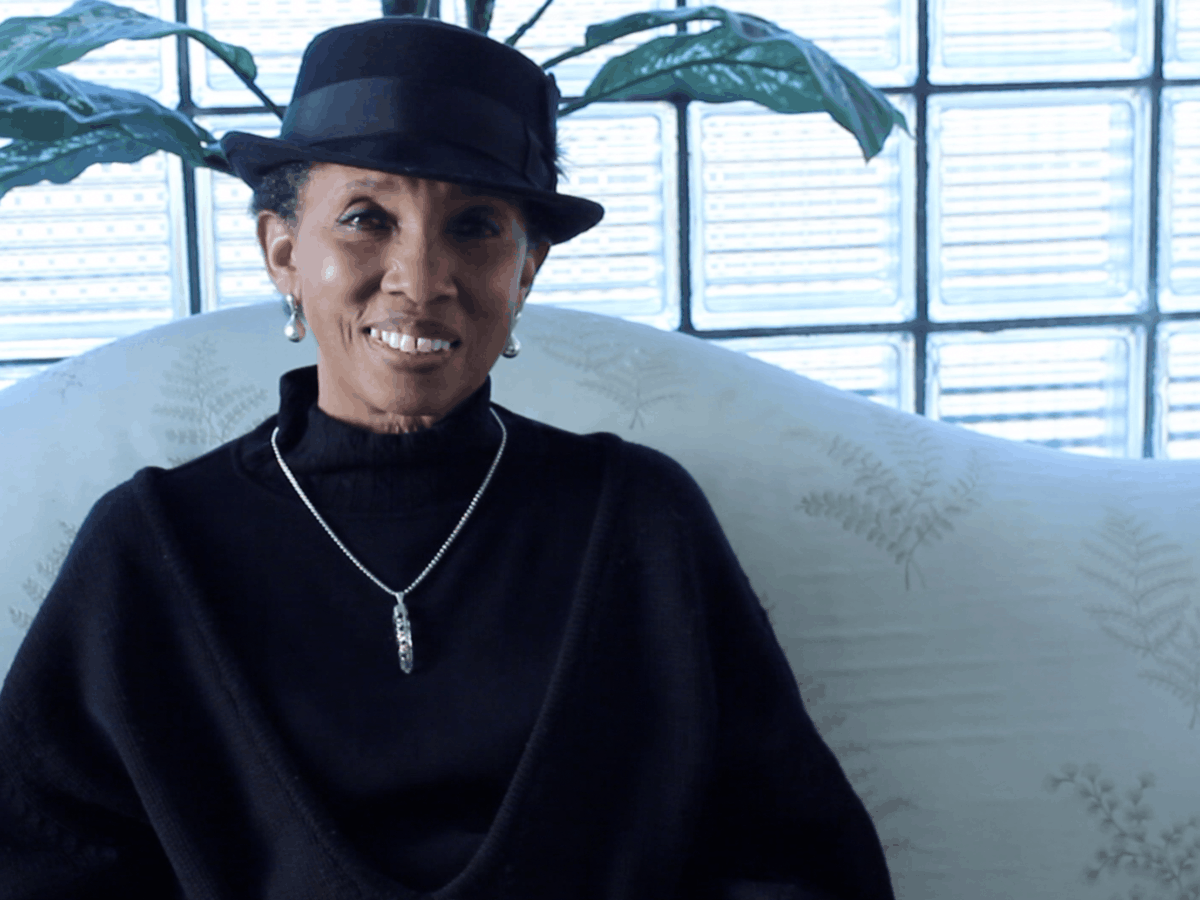

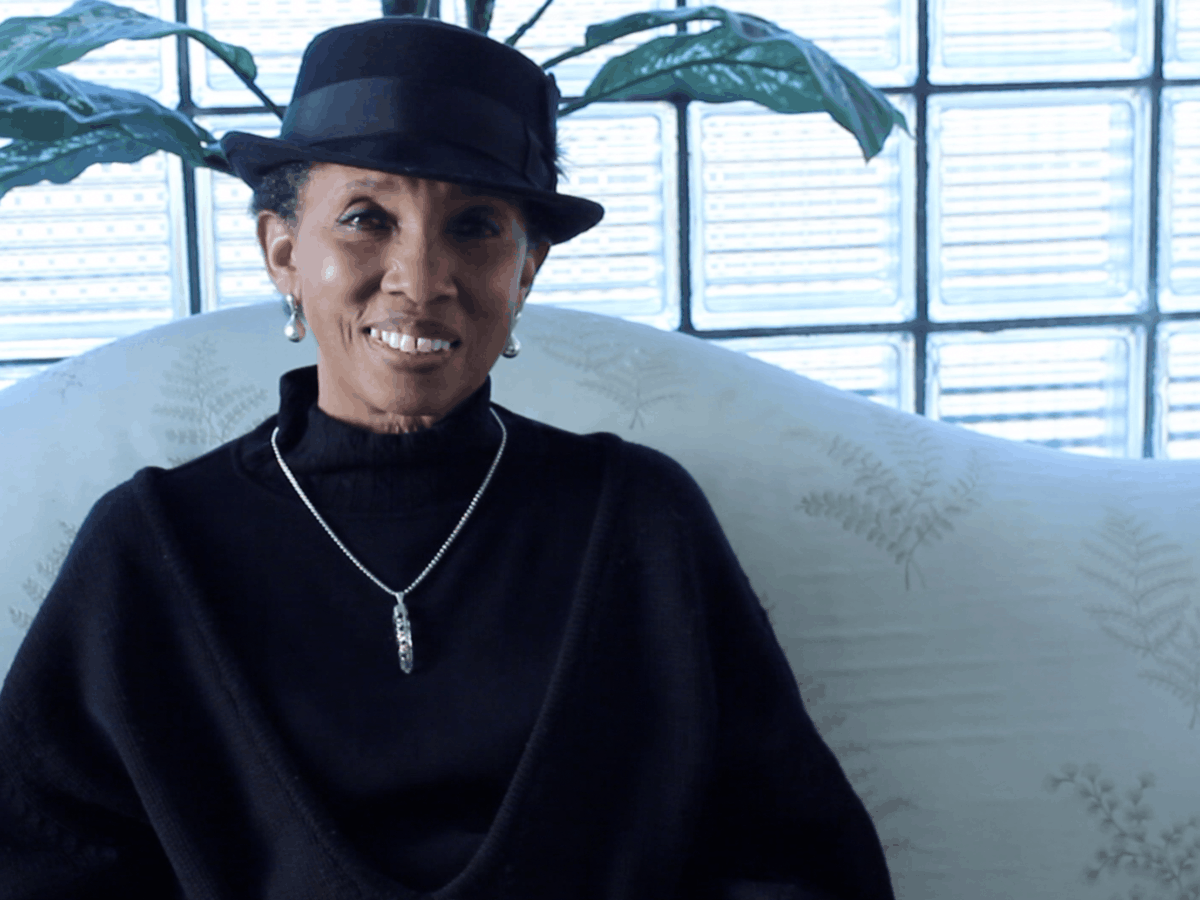

Doris Stith went through all of her school years in a segregated school district in Tarboro, graduating from high school in 1970. In the video below, Stith shares some of her experiences growing up as well as her hopes for the community she still calls home.

I first met Stith at a dinner in Tarboro celebrating Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr. It was MLK weekend, and when I learned I was going to do a short profile on Stith, I decided to join in on this event where she was the emcee and see her in action.

I soon learned that to see Stith in action is simply to watch grace unfold. Though she was the dinner’s emcee, she spent the bare minimum time behind the podium. Instead, when her eye caught a familiar face in the audience (and in Tarboro, Stith knows many faces), she quickly moved to their table to catch up and have a hello. In no time, she would have an update on their family members and turn to me with a quick word on how far back the two go.

As she introduced the 29th Annual Commemorative MLK Banquet, she spoke to the evening’s theme: “All Life is Inter-related.”

“Let’s break bread together. Let’s love one another,” she said.

The next time I saw Stith was the following Monday morning, at an MLK breakfast in downtown Tarboro. Whenever the church choir sang, Stith rose out of her seat. She’s the sing along, clap along type. She chooses joy.

After the breakfast, we made our way over to the MLK march, along with hundreds of other community members of all ages, bearing the chilly early morning. Before the march, Stith walked from group to group, almost like a bee goes between sets of flowers, happily embracing a community of friends. During the march, she commented at how happy she was to see so many young people and often engaged in conversation with people she didn’t know.

Through one action, in particular, Stith demonstrated the kind of person she is. She has an uncanny ability to pay attention to everyone, and to notice those others might not. She saw a woman making the walk, determined and with a cane. Over time Stith stayed with this woman and dropped back with her as she continued the walk despite her knee. The two of them were at the end of the line, followed by a police car closing out the march and holding the road.

Stith’s dedication to community work in Tarboro comes after a 17-year stint of community work in Charlotte. Tarboro, however, is her home. Stith was the fifth child of seven, born to a farming family who proudly grew cucumber, corn, and tobacco. Her father had dropped out of high school to help with the farm, and he instilled a work ethic in all of his children. All of the boys went to the army, and all of the girls ended up in college.

Stith said growing up in the segregated south wasn’t a harsh experience. She said she loved her education, graduating in the last all-black class at W.A. Pattillo High School in 1970 (the class will be celebrating their 50th-year reunion next year). And when I asked her about segregation outside of schools, like public places and use of water fountains, she said that her mother had smartly found a tactic of making her children less aware of the racism surrounding them.

Her mother had told them the water in town was dirty, and that’s why they shouldn’t drink it.

Her first experiences with blatant racism took place instead in Greensboro where she attended a pre-college summer experience hosted by NC A&T. A white woman, she recalled, came over to the table where Stith and her friends were eating at a pizza restaurant (pizza was also a new experience for Stith).

The woman stood over Stith and exhaled cigarette smoke over her face. She and her friends sat still and did nothing to escalate the situation, patiently waiting for the woman to leave.

Stith went on to attend UNC-Chapel Hill, actively taking part in groups like Black Student Movement (BSM). Stith was named Miss Black Student Movement her sophomore year and served as managing editor of Black Ink, BSM’s newspaper. While she found this black community of students, she said she was often the only black student in many of her classes.

“We just wanted to be successful students,” Stith said. “We were young people trying to find our way.”

After college, Stith found her passion in community work — previously at the C.W. Williams Community Health Center in Charlotte and more recently as the Executive Director of the Community Enrichment Organization in Tarboro, where she has served for the past 26 years.

Editor’s note: James Ford is on contract with the N.C. Center for Public Policy Research from 2017-2020 while he leads this statewide study of equity in our schools. Center staff is supporting Ford’s leadership of the study, has conducted an independent verification of the data, and has edited the reports.