Share this story

- Smokey Mountain Elementary School is teaching the history and traditions of its oldest residents — the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians — to students. @jcpsnc

- "It's good to know that there's a respect and a level of recognition of the culture in the area and what it means,” a Smokey Mountain Elementary School school social worker said. @jcpsnc

|

|

“Osiyo.”

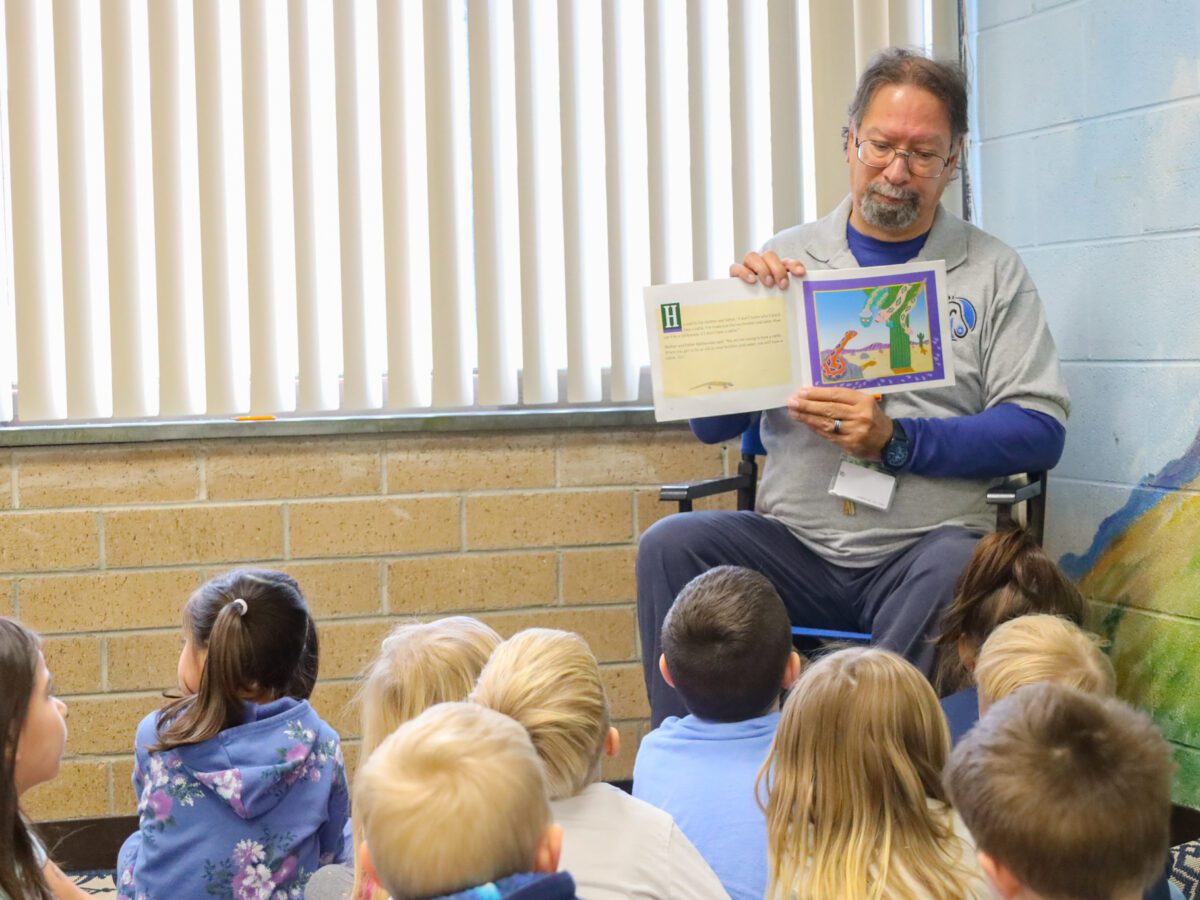

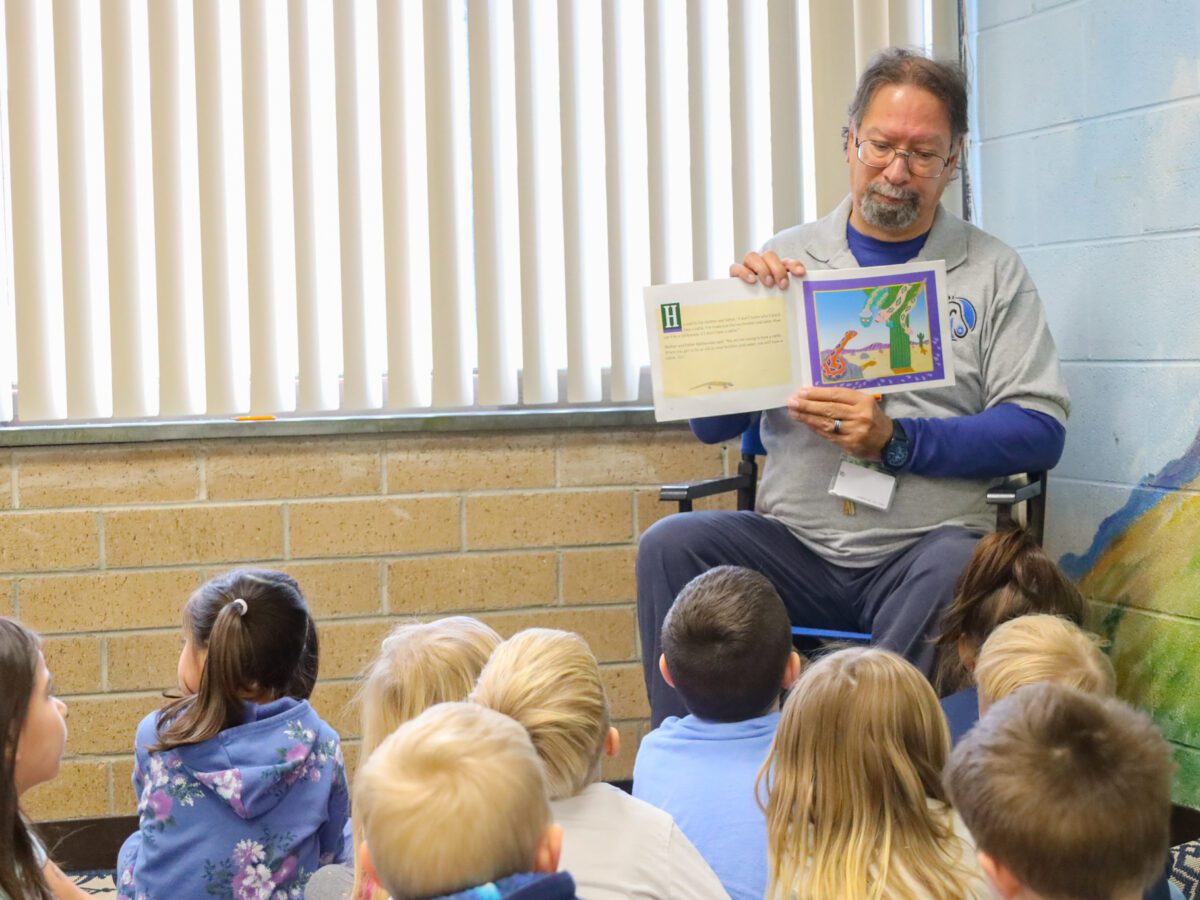

This is how Robert Eldridge greets his classes at Smokey Mountain Elementary School in Whittier, NC.

In Cherokee, “Osiyo” means “Hello.”

Using Title VI Indian Education Formula Grants, Jackson County Public Schools employs Eldridge as a Cherokee culture specialist, who teaches Cherokee and non-Cherokee students at Smokey Mountain Elementary School about the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians.

Smokey Mountain Elementary School is nestled right near the Qualla Boundary – the home territory of the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians. According to Mike Treadway, the school’s principal, about 40 percent of the students at Smokey Mountain Elementary School are enrolled members of the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians (EBCI).

The Cherokee culture specialist position stayed vacant for nearly four years until last fall, when Robert Eldridge’s grandchildren, who attend the school, told him about the opening. He’s been in the role since the fall of 2021.

From the time he took over as principal, Treadway said using this position to uplift Cherokee culture and history was a priority – for all students at the school.

“I wanted that leadership connection back to the tribe,” Treadway said. “One of the misconceptions about our class is that it’s only for our Native American students. We want every kid that we have to be a part of that, to experience that.”

Teaching Cherokee language

Treadway says teaching Cherokee language was never a priority when filling the position. But learning the Cherokee language has quickly become a favorite part of the class for Eldridge’s students.

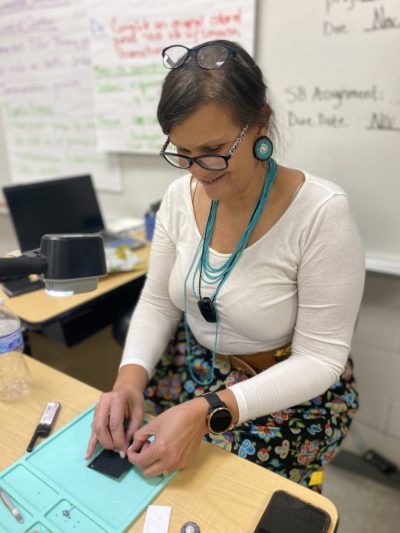

Eldridge starts by teaching students the basics: numbers, colors, animals, and greetings. When they enter his classroom, Eldridge exchanges Cherokee greetings with students. Sometimes they model the words he says, other times they respond to the questions he asks, or repeat words after him.

Eldrige may ask, “Who can tell me the meaning of the Cherokee word yona?” with students responding, “Bear!”

The Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians estimates that it has about 200 fluent Cherokee speakers. For many students in his classes — Cherokee and non-Cherokee alike — this is their first introduction to the language. While Eldridge is not fluent, he says that teaching has helped increase his Cherokee vocabulary.

“Believe it or not, teaching – that has helped me more than anything,” Eldridge said. “As my kids get older, I want to expand their vocabulary.”

Blending Cherokee history and current events

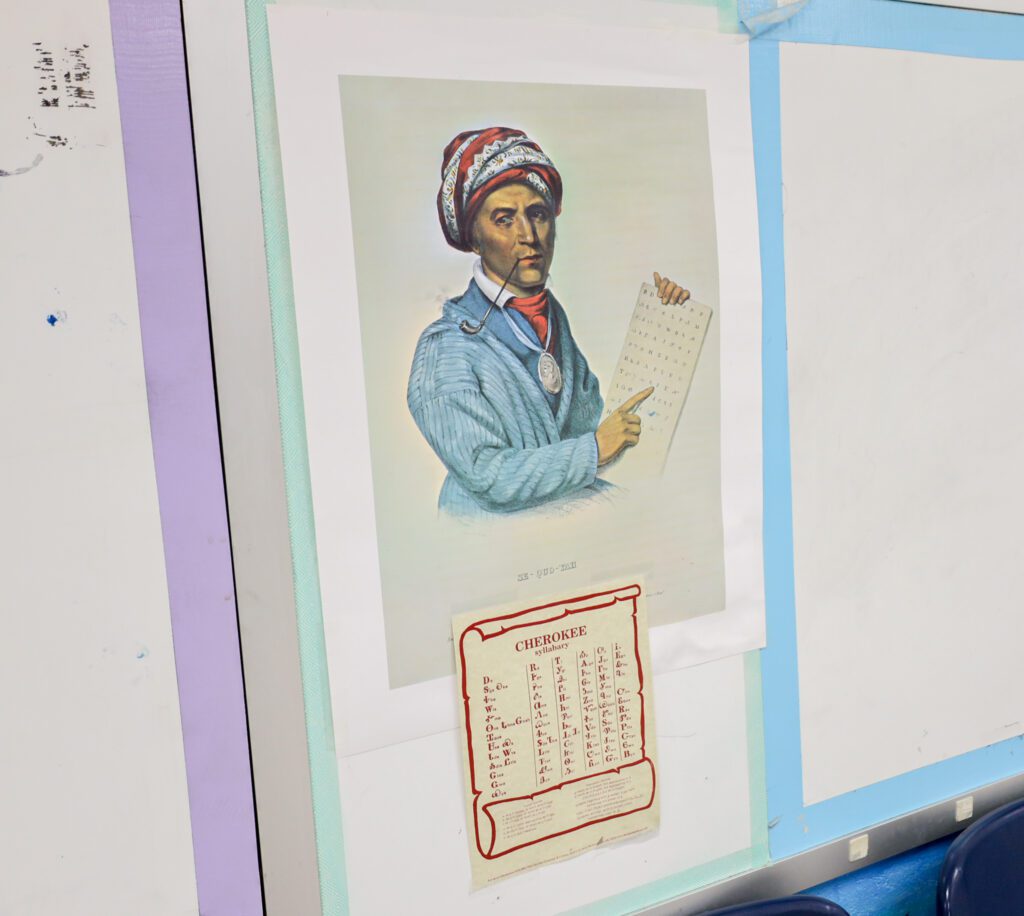

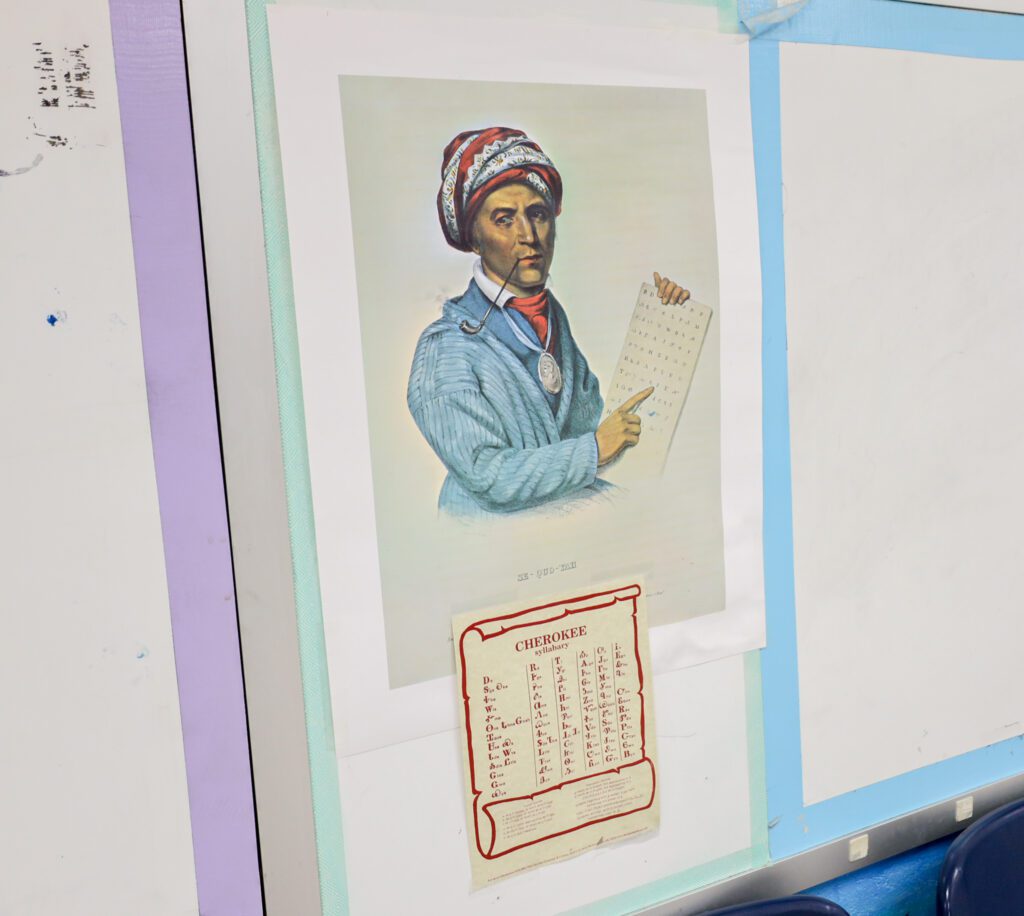

For older students, Eldridge includes more Cherokee tribal history and blends in current events related to Indigenous peoples. This might include teaching students how to respond to and understand stereotypes of Indigenous peoples. Sometimes it includes lessons about significant events and people in Cherokee history – including Sequoyah.

“Now, has anybody heard of a man called Sequoyah?” he asks.

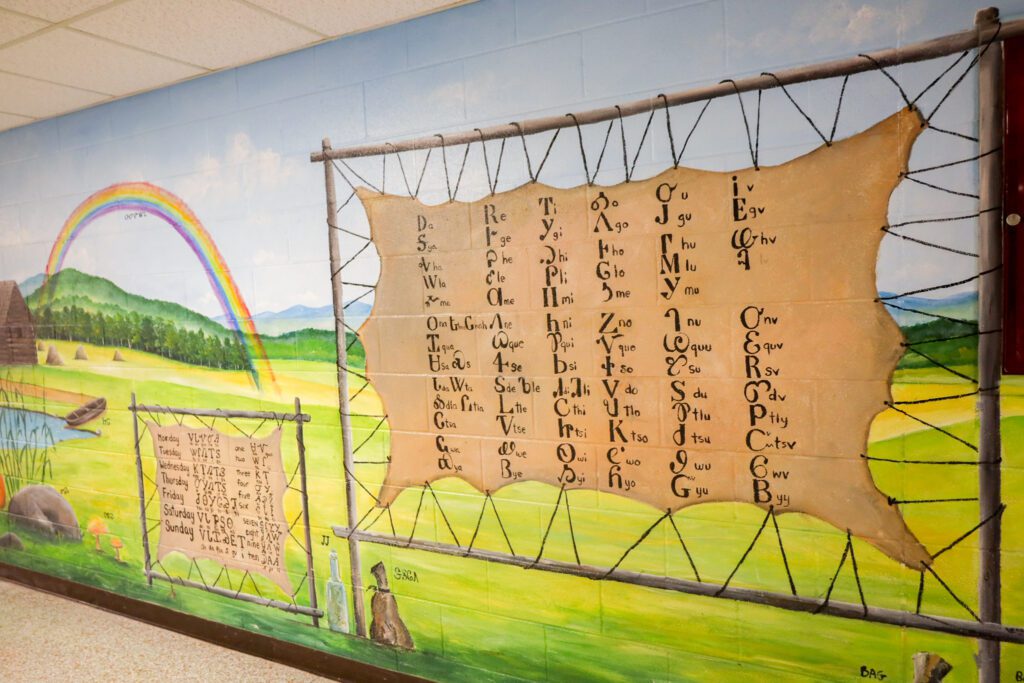

Sequoyah is credited with creating the Cherokee Syllabary. And since he began in this role, Eldridge has taken eighth graders in his class on a trip to the Sequoyah Birthplace Museum in Vonore, Tennessee, where they take time to learn more about Sequoyah’s life and his journey to creating the Cherokee syllabary.

Jolene Sneed, the school social worker, said what students learn in Eldridge’s class and on these trips creates a sense of pride for Cherokee students.

“It also builds pride in the students that didn’t even know, ‘that’s my culture,’’ Sneed said. “Just learning their own culture too. It was a really big deal and we get to do that all the time.”

Building this pride sometimes includes discussing difficult topics — like Indian boarding schools. These boarding schools forcibly assimilated Indigenous children by renaming them with English names, cutting their hair, and restricting cultural practices.

After the U.S. Department of the Interior released a report documenting Indian boarding schools across the country — including four in North Carolina — Eldridge shared this dark history with students. He was able to share stories of boarding school survivors.

“Being able to write my own curriculum allows me to go out into areas that most teachers can’t,” Eldridge said. “So, for one whole week, we looked at the boarding schools.”

But, discussing heavy topics like boarding schools and removal isn’t easy, so Eldridge takes time monitoring his students by asking, “How do you feel?” throughout these kinds of lessons.

Looking at the bigger picture

The Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians is just one of 574 federally recognized tribes in the United States, so Eldridge spends time sharing details about other tribes and teaching students some of the ways that tribes are distinguished by region, language group, and more.

“You live in a little bubble here in Cherokee, and everything’s about Cherokee,” Eldridge said.

Taking time to discuss the languages and traditions of other tribes was important to Eldridge, being that he is a member of another tribe, the Sappony, who are a state-recognized tribe located in Person County and Halifax County, Virginia.

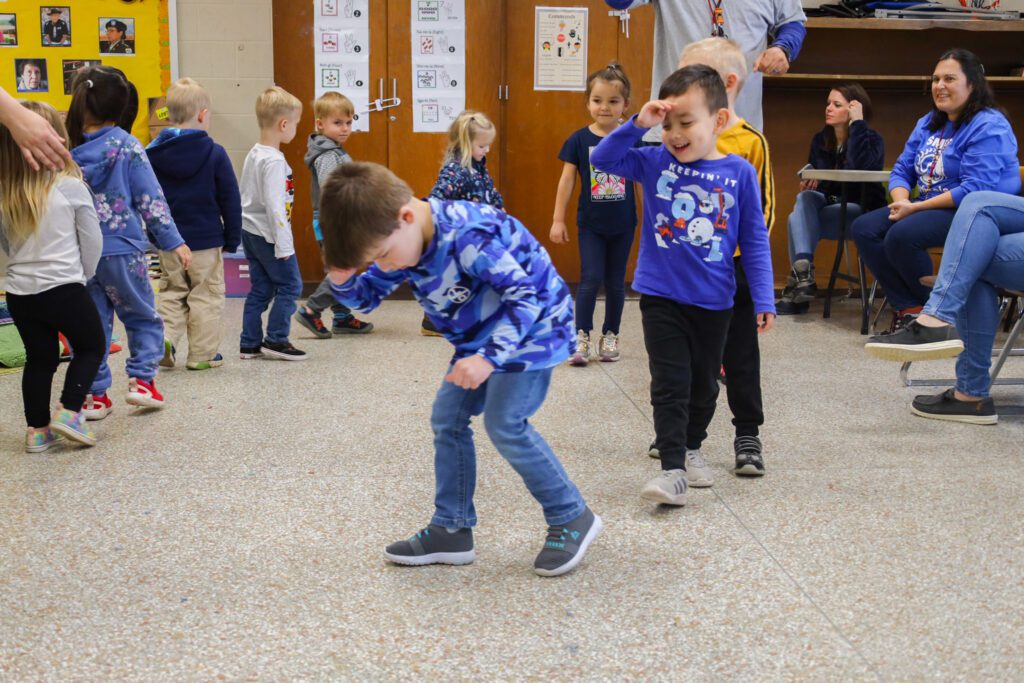

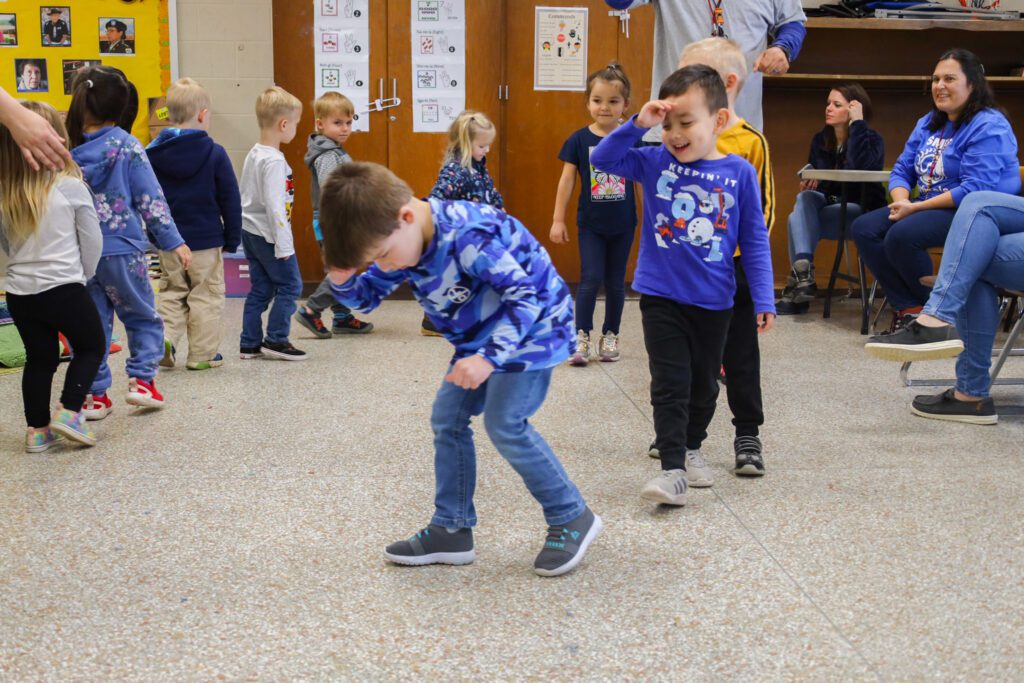

For his younger students, Eldridge incorporates dances, songs, and even tells Cherokee stories.

“These little ones are just so much fun,” Eldridge said. “They’re little sponges.”

These students grasp the language and routine of Eldridge’s class quickly through the repetition of songs, dances, and games.

Creating pride in community and culture

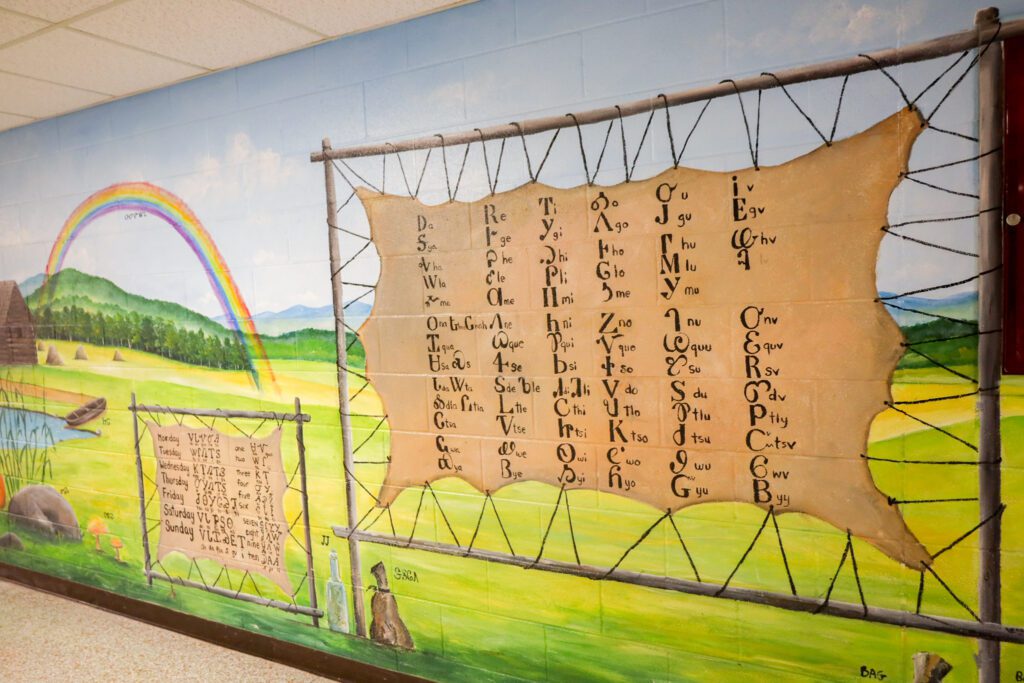

Throughout the school, there is art on display from local Cherokee artists and murals depicting the Cherokee syllabary to emphasize the tribe’s proximity to the school and community.

“I think it’s very welcoming, in the sense of building community because there’s such a large population of Cherokee students. It’s good to know that there’s a respect and a level of recognition of the culture in the area and what it means,” Sneed said.

Sneed emphasized that teaching Cherokee culture enriches the school and is an experience that resonates with students and community members alike.

Superintendent Dana Ayers said by having this class on campus, Cherokee students feel seen and accepted, while non-Cherokee students learn how to respect the tribe’s culture and history. She said that Cherokee students don’t have to feel singled out because their classmates have been introduced to their culture, too.

“What comes with that acceptance is a level of inclusivity,” Ayers said. “They’ve grown up with this familiarity and the interaction.”