Health and education representatives struggled to find a common starting point Thursday as they dove into a large task: creating a coordinated system of care and education for children from birth through third grade.

The state’s early childhood and K-12 education systems are largely disconnected, as are the bodies that oversee them. During last year’s legislative session, the legislature created the B-3 Interagency Council to bridge the two, comprised of individuals from both the Department of Public Instruction and the Department of Health and Human Services.

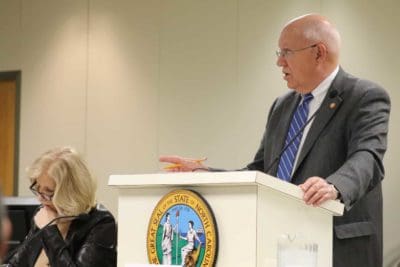

“I think we’re looking at the pieces before we can envision what we want,” said Sen. Michael Lee, R-New Hanover. Lee expressed concern that members were stuck on details with a report from the council due in the next month. “Let’s take a step back and say, ‘What’s the vision?'” he said.

The council’s mission reflects a recent focus on services for children in their first years of life, which are critical to their brain development and functionality, as well as continued attention to third grade as a mark for reading proficiency. That mark, research shows, indicates a child’s likelihood of graduating high school on time.

Rep. Craig Horn, R-Union, said he plans to take the council’s work and attach political momentum and financial support from the larger General Assembly. Thursday was council’s second meeting, and members began to prioritize what aspects of a new system deserve the most attention.

Out of seven categories taken from the council’s charge, members ranked these three the highest:

- data-driven improvement and outcomes,

- teacher and administrator preparation and effectiveness,

- transitions and continuity

Other categories included:

- standards and assessment

- instruction and environment

- family engagement

- governance and funding

“Our data collection is a little bit fragmented,” said Nancy Brown, board member of the North Carolina Partnership for Children and an expert on early childhood education. “(There is) a lot of data collection going on, a lot of it not being used, but no consistency and collaboration or even knowledge of all those different data collection systems and how the collective data could be used.”

Brown said finding and tracking where children live and if they are in a formal early childhood care setting is a good place to start. Tracy Zimmerman, executive director of the North Carolina Early Childhood Foundation, said measuring the right things and then making sure that data is used in practice matters.

The foundation has led a cross-sector effort called the North Carolina Pathways to Grade-Level Reading Initiative to find what indicators and actions are important in preparing all kids to read on grade-level by third grade. Birth weight, for example, makes a difference for a child’s likelihood to reach third grade reading proficiency. Zimmerman said that kind of high-level data can then be broken down to show where resources should go.

“If you really want to tell that story, then you look and you actually disaggregate the data, and you say, ‘Wow, African-American babies are so disproportionately affected by that,'” Zimmerman said. “‘Well, our strategies might need to really hone in on that population.'”

Several members expressed concern that teachers and administrators in early childhood care and education are held to standards lower than those in the state’s K-12 system.

“We spend a lot of time talking about how ill-prepared our early childhood educators are compared to the K-12 (educators) — the level of support and education that they get …” said Elisha Freeman, the executive director of the Children & Family Resource Center.

Brown said all caregivers, including those at home, play vital roles in children’s health and development.

“Parents and adults who work with children are very significant in the lives of children,” she said. “Truth be known, in a way, public education is suffering from an attitude that’s over half a century old, when they said to parents: ‘You let us teach. You go home and just care.'”

In a breakout group, half of the council decided that, in an ideal world, teachers and administrators interacting with children before fourth grade would function in an “early learning system.”

Licenses, members said, should be attached to individuals instead of programs throughout the birth to third grade timeframe. Currently, the state gives licenses to early childhood programs and K-12 individual teachers.

“It would be based on you,” Zimmerman said. “As part of this, the setting wouldn’t determine your level of knowledge, so whether you were in a childcare program or a school or what have you.”

The other half of the council came up with ideas for a seamless transition from the perspective of children and their families. One of those ideas was a toolkit specific to the community where the child lives that gives information to parents on what early childhood education options are locally available and how to determine if an option is high-quality.

Members also brought up the idea of “parent navigators:” individuals who can help parents or caregivers in the process of raising their child with helpful resources and information.

“So if I don’t have transportation to xyz resource, How do I get that?” Freeman said as an example of a situation where the parent navigator could be helpful.

Freeman also said early childhood teachers need to communicate their teaching methods with elementary school teachers.

“We’re experts here and we need to push that up because our K-3 teachers need to know that as well,” she said. “And so it’s two different styles of teaching a child and so … how (do) we unite the best of both systems for that sort of seamless transition?”