This article is the second in a series this week on schools in Western North Carolina.

Clay County Schools

In Clay County, 1,485 elementary (pre-K to grade 4), middle (grades 5-8), and high school students attend three schools on one 52-acre campus against the backdrop of some breathtaking mountains. All of the schools run on the same bell schedule: 7:55am to 3:00pm. The school buses bring all of the students into campus – with kids of all ages riding the same bus.

In addition to the central campus, a couple of things are worth noting. A day care center is located on site for the children of teachers.

Students are only allowed seven absences before they are required to attend Saturday classes. Universal school breakfast is offered.

Superintendent Mark Leek wrote his doctoral dissertation at Western Carolina in 2003 about the schools of Clay County since 1850.

And community involvement is evident everywhere, but perhaps nowhere more than the most spectacular outdoor classroom I have ever seen.

Hunter safety classes

“The conservation of natural resources is the fundamental problem. Unless we solve that problem it will avail us little to solve all others.”

– Theodore Roosevelt, U.S. President

Memphis, Tennessee, October 12, 1907

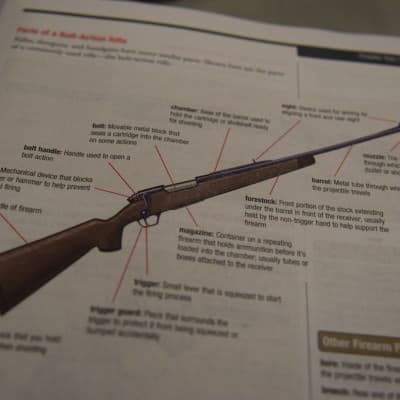

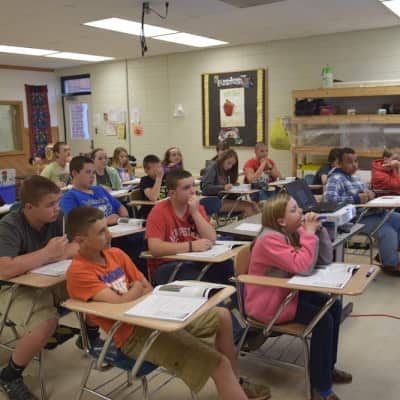

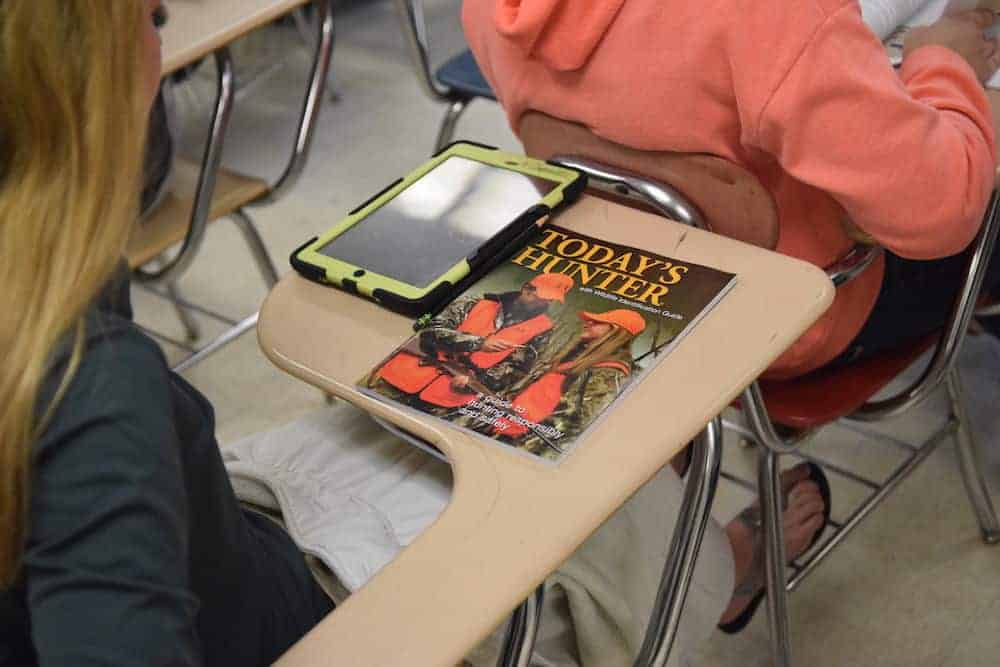

As Becky Stewart, the CTE director, walks me down to a hunter safety class, she notes, “We are a community of hunters, fishers.” Seventeen eighth graders, including six girls, file in to the class and take a seat. The class is being taught by Chris Roberts, a teacher who has been hunting since his father took him when he was in elementary school, and Officer Posey, a school resource officer.

Roberts asks the class why they thought he was teaching hunter safety. Responses included, “so we don’t die while hunting,” “so we don’t make dumb decisions,” and “so we are safe when we are hunting.” Roberts says that by teaching responsibility, safety, hunting basics, etiquette, and conservation, classes like these ensure the continuation of hunting across the United States. He aspires to “keep the sport going by training the next generation of hunters.”

If the students pass this class, they will get a hunting permit, which will allow them to apply for a hunting license. The school would like to start a shooting team.

One student tells a story of turkey hunting with his father. The student accidentally put a 10-gauge shell in his 12-gauge shotgun. Before he fired his shotgun, his daddy realized something was wrong. Roberts says this could have been really dangerous – and stresses the organization of ammunition so that it is easy for students to match up ammunition with the firearm they are using. He mentions more than once that gun barrels do explode.

Roberts talks to the students about tension points between those who hunt and those who don’t. Trespassing is a big one, and he notes that written permission and detailed agreements about hunting arrangements with landowners are imperative, spelling out the use of all-terrain vehicles (ATVs), what times of day, and what the landowner considers too close to houses.

In the next class of 18 seventh graders, 12 of them had already been hunting before. Officer Posey worries about the girls. Many have not grown up hunting, but they will date hunters, and she wants them to know how to be safe.

Ag in the classroom

Married to Chris Roberts, the teacher of hunter safety, is Rachel Roberts. I attend her Ag Science high school class along with two seniors, Chad and Eric.

This is not your normal classroom.

Eggs are incubating on one shelf. The students are encouraged with a grant from NC REAL to start small businesses. These chicks will be sold to those in the school community for $2 – that’s $1 below fair market price in these parts.

Soil samples with different fertilizers line a table.

Students bring and leave work boots because on most days they are outdoors gardening.

Roberts asks the students to bring me up to speed. It is clear that participation is required in this classroom – even from visitors. The students are checking out what looks like saplings in boxes.

Chad starts by saying, “We’re playing God.” He proceeds to tell me how they have been grafting apple trees. First you make an incision in root stock. Then you take a branch from the type of tree you want to grow. You put the branch in the incision on the root. Chad says this is like a key fitting into a door lock. This causes the root to grow the type of tree that has been grafted onto it. Chad grafted a Stayman-Winesap on N112 root stock. The root stock, he says, restricts how big a tree can grow. Since labor is the largest expense for apple growers, smaller trees are better. I learn later that Chris, Rachel’s husband, is a fourth generation apple grower.

Roberts, as it turns out, was just getting started. She hands me a worksheet so I can take notes during a lesson on designing your own soil. “You can be a doctor of soil,” she proclaims to the students with a smile.

We draw a pie chart and learn that the components of soil include 45 percent minerals, 25 percent air, 25 percent water, and 5 percent organic matter. Roberts walks us through soil particles from big (like sand) to medium (like silt) to small (like clay). Loam soil, she says, is 40 percent sand, 40 percent silt, and 20 percent clay. It is the best soil to grow in.

Next, we get to practice by concocting our own recipe for soil. We will be planting Christmas limas. While Roberts moves over to a table to get all of her supplies ready, she asks us to develop a hypothesis about the ideal soil mixture for this plant. Turns out she is a plant biologist with a degree from Cornell University. There is going to be a prize for the student with the most growth over 10 days.

Roberts then tells us a story. In the 1800s, the local Cherokee were rounded up, and all they knew was they were going for a long walk. The women were the agriculturists, and they knew that the only way they would survive was to take seeds to plant. They sewed the seeds into the hems of their skirts and walked them to Oklahoma. The seed saver exchange now works to save and share such heirloom seeds.

“These seeds have incredible stories,” says Roberts.

Next, we (and that is the collective we including me) planted our Christmas lima beans. But first she asks us to smell donkey poop, which is used as fertilizer. The students balk. I am game. Remember in my article yesterday I noted that something unexpected always happens when I visit a school? This was it. There is no odor other than that of dirt. She tells us about the benefits of organic fertilizer, and then moving on she notes casually that Christmas limas like clay. It’s a hint for us as we concoct our soil.

There is a tub of silt. When the students realize it is cow manure, they roll their sleeves up. Turns out these boys don’t really like to get their hands dirty. There is a tub of sand and a tub of clay. We mix our soil, noting our percentage of each soil component. We plant two limas just under the surface. Eric waters them for us, and puts them under lights on shelves.

And we are not done.

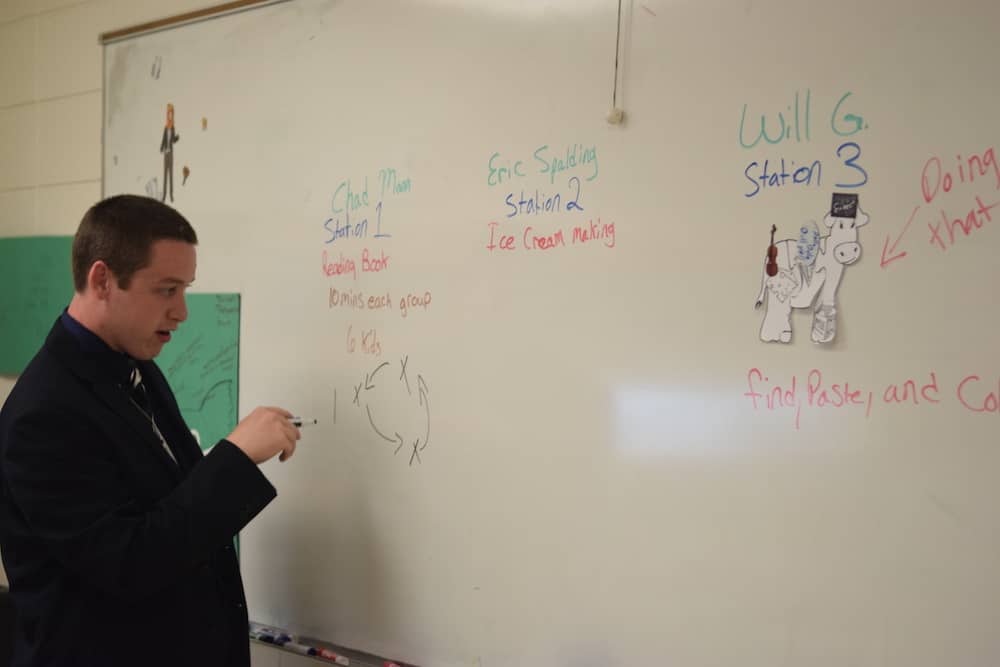

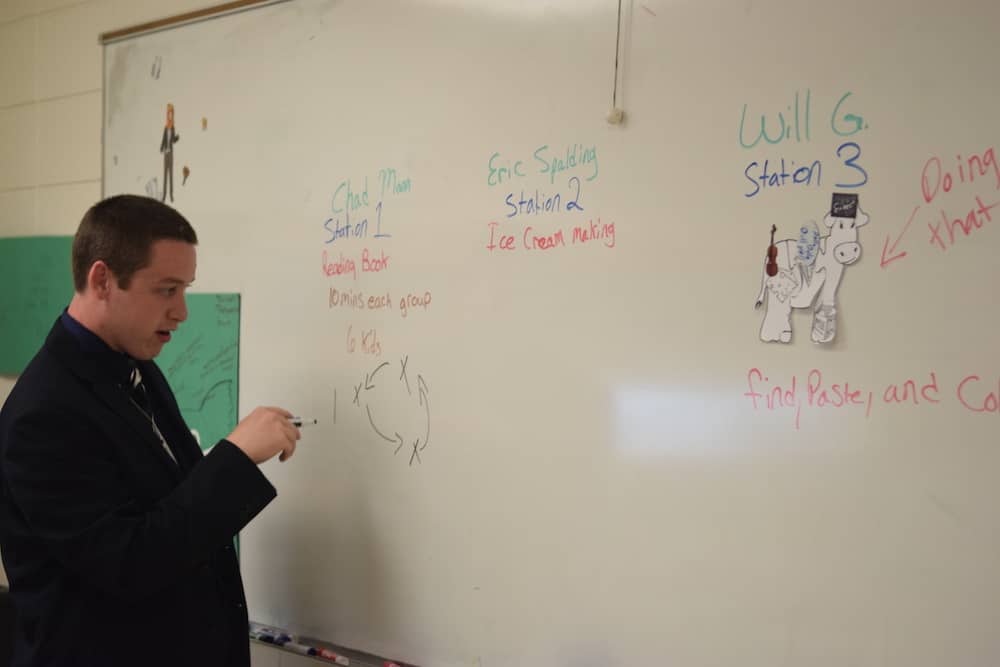

The next day, this class will be teaching a pre-K class. The students have been working on the lesson plan, and now they are going over it to make sure it will run smoothly. They are setting up three stations – each station will last 10 minutes and include six students. The stations will rotate in clockwise fashion. Chad is going to be reading a book. Eric is going to teach the students how to make ice cream in a Ziploc bag. Using a puzzle, Will will teach the students what products are made from cow’s milk.

Ziploc Ice Cream

Yields 1 cup

Ingredients

1 tablespoon sugar

1/2 cup milk or half-and-half

1/4 teaspoon vanilla

6 tablespoons rock salt

ice

Preparation

- Put milk, vanilla, and sugar into a quart size Ziploc bag, and seal it.

- Fill a gallon size Ziploc bag half full of ice, and add the rock salt.

- Place the small bag inside the large one and seal well.

- Shake until mixture is ice cream, about 5 minutes.

- Cut off a corner of small bag, squeeze into bowl or cone and enjoy!

Roberts is not just growing produce, she is growing community relationships. Chad says, “they [the pre-K students] see me at Ingles, and they just run up to me.” Roberts looks up at me. “They love him,” she says.

And we are not done.

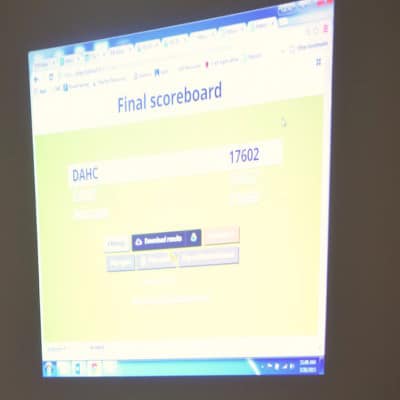

Roberts hands me an iPad. She has developed a game using a program called Kahoot! that incorporates the standards for this Ag Science class. It’s a formative assessment to test what we have learned so she can provide remediation in real time. Needless to say, I did not win.

At the end of the class, which I noted was at 11:10, I asked what time we started. 9:40. I am amazed how much I have learned, how much we have done in an hour and a half.

Best class ever.

Growing a vibrant ag program

Rachel Roberts does not plan to be a teacher forever. Maybe that is why her energy now seems boundless. We use her planning period to go and do and see and talk.

This is Robert’s first year teaching in the Clay County Schools. She previously taught at a charter school in Cherokee. There she received a grant from the local Farm Bureau. One thing led to another.

She is teaching 7th and 8th grade agriculture, which she notes can’t be taught well without including biology, chemistry, physical science, and her list went on and on. She is teaching the Ag Science class that I attended and also Ag Production.

The school is in the process of building a $40K greenhouse. Just past the greenhouse are raised beds of lettuce and green onions and then a field of 1500 strawberry plants.

Most of the strawberries will be harvested through a u pick program. But with the help of $300 grants, three students have set up business plans: one will be selling freezer jam, another will pick and sell berries, and another will sell chocolate covered strawberries. These products will be available at the local farmer’s market on Thursday evenings and Saturdays.

The school may try to get GAP certified to grow lettuce to use in the school cafeteria.

Roberts has big plans to raise livestock on 17 acres of land that was donated to the school off campus. It seems like a natural extension of the work she is doing.

It is impossible to believe that this school has not had an ag program since 1989.

Communities In Schools: Clay County

Remember that community involvement I mentioned earlier? Everywhere I went in Clay County, people talked about the work of Theresa Waldroup and Communities In Schools of Clay County. With about $40,000 a year, this affiliate of CIS makes a big difference for the students and the schools. In 2013-14, CIS: Clay County served 143 children and 116 adults in temporary crisis by providing, shoes, coats, clothes, school supplies, scholarships, caps and gowns for graduation, food, electric bills, and fuel. Tutors provided assistance to 117 students in reading and 90 students in math. Band instruments were purchased or repaired for 50 students. 25 student mentors and 38 adult mentors provided more than 2700 volunteer hours.

“Maybe there’s a way out of the cage where you live

Maybe one of these days you can let the light in

Show me how big your brave is”

– Brave, Sara Bareilles

CIS: Clay County believes that every child needs and deserves five basic things: a one-on-one relationship with a caring adult, a safe place to learn and grow, a healthy start and a healthy future, a marketable skill to use upon graduation, and a chance to give back to peers and community.

The mantra of CIS: Clay County? Be brave for our students.