High child poverty is increasing nationwide, and the country’s rural places have a disproportionate share of children living in persistently high poverty. That’s according a new report from The University of New Hampshire’s Carsey School of Public Policy.

The report defines high child poverty as counties where 20 percent or more of the children are living in poverty and persistent child poverty as those places where high poverty was found at each measure over a thirty year period, from 1980 to 2010.

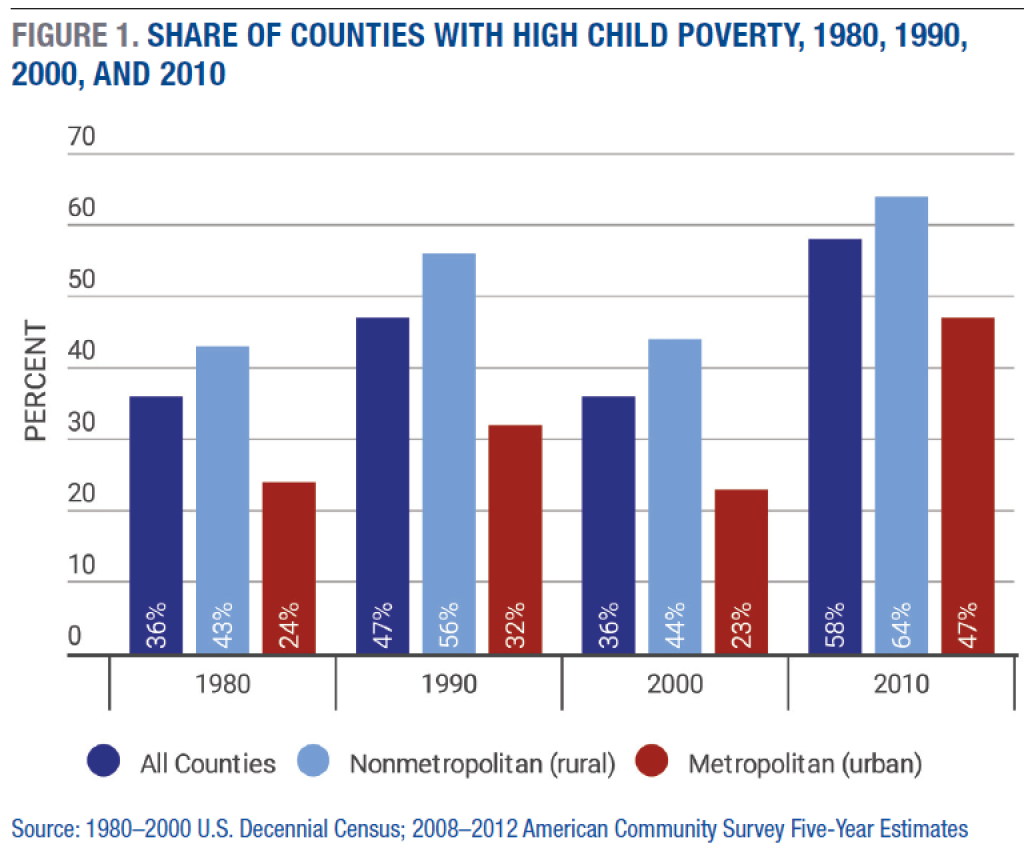

Given what we learned earlier this year, it comes as no surprise that rural counties in this country have a disproportionately higher share of high child poverty compared to urban counties, but even in the context of the Great Recession, the dramatic increase in rates for both in 2010 were surprising. Between 2000 and 2010, there was a 20 percentage point increase in the number of rural counties with high child poverty, an increase of 44 to 64 percent, and a 24 percentage point increase in the number of urban counties, from 23 to 47 percent.

As the Carsey report notes, “The recent economic recession fueled increases in the incidence of child poverty, though in many instances the recession just made a bad situation worse: high child poverty has persisted in many areas for decades, underscoring that it is not just a short term result of the recession.”

It’s a theme that has been noted elsewhere, most notably in the 2010 State of the South report, authored by EdNC columnist Ferrel Guillory. The Great Recession exposed persistent racial and economic inequality that most considered a remnant of a bygone era, in this state, in the South as a region, and across the nation. A period when robust economic growth masked an increase in jobs that did not provide living-wage salaries or benefits.

Progress made on social issues appeared stalled as the nation began its post-Recession recovery. As the Carsey report highlights, poverty still disproportionately breaks along racial and regional lines, noting that “77 percent of persistent-high-child-poverty counties have a substantial minority child population, compared to just 54 percent of all counties.”

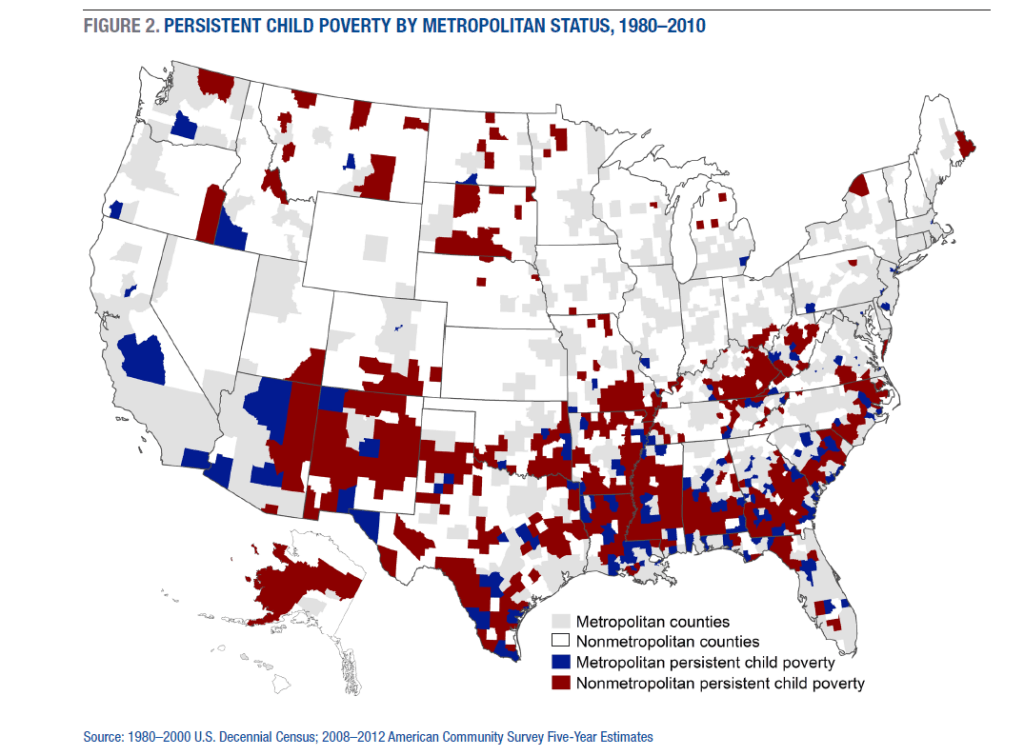

The Carsey report is brief and does not provide a state-by-state analysis of their findings, but the national maps provided do offer a glimpse as to where in this state persistently high child poverty is most prevalent. The map below shows counties, both urban and rural, where high child poverty — with greater than 20 percent of the child population in poverty– persisted over a three-decade period.

For North Carolina, those counties are predominantly located in the Sandhills and track east of I-95 up to the Virginia/NC border. And while it includes a few splashes of blue for some of the eastern North Carolina metro counties, it’s mostly a lot of red, indicating rural places with persistent high child poverty. It is a band of red that connects eastern North Carolina to the Deep South and into the Mississippi Delta. A visual reminder that as the rest of the state has progressed economically over the last thirty years, there are places in this state that are closer in kinship to the Delta than the Triangle.

But why does the discussion of poverty–and particularly the ongoing intergenerational poverty identified in the Carsey report– matter for our education policy in this state?

The Carsey report opens by noting that children living in poverty are “… less likely to have timely immunizations, have lower academic achievement, are generally less engaged in school activities…” Into adulthood, that disadvantage can affect health, earnings, and family status. In the three-decade time frame from which data was pulled, the report reminds us that “… at least two generations of children and the families, organizations, and institutions that support them have been challenged to grow and develop under difficult financial circumstances.”

The report also points to the differences in poverty by place, of how poverty in a more affluent community, where good schools might be more accessible, compares to life in places where chronic poverty is the norm, where infrastructure is lacking, where schools may be underfunded, and where opportunities for economic advancement scarce.

Just last week, NPR did a feature on homelessness in rural communities, noting that while homelessness is a difficult count to measure in the best of circumstances, it is even more difficult in rural places where the homeless population may not be as concentrated and out in the open as in urban places. The under estimate affects rural communities ability to secure federal funding to serve homeless individuals and families.

Earlier this week, the latest installment in WUNC’s Perils & Promise: Educating North Carolina’s Rural Students series looked at the challenges facing young African-American males in rural communities, were education options are limited.

And Carsey itself released a report in October of last year noting an increase in the abuse of prescription painkillers by rural youth. And another in July noting that fewer eligible rural households participated in the National School Lunch and School Breakfast programs than their urban counterparts (though it should be noted that lowest participation rates were for suburban households).

A child in poverty is a child in poverty, regardless of the address. But to ignore the cultural, social, and physical geography of a place is to ignore the fact that the barriers to success and the pathways to opportunity might look different depending upon where a family lives.

It also means that our collective policy prescriptions might look different for a child in the Triangle than one in the Sandhills.

The Carsey report concludes with the following observation:

The problems with which all poor people struggle are exacerbated in rural areas by remoteness and lack of support services. For instance, limited access to comprehensive food stores with fresh fruits and vegetables creates food deserts in rural areas, especially for the rural poor with limited access to reliable transportation. That these persistently poor rural areas exist far from the media and governmental centers of a metrocentric nation may make it difficult for policy makers, the media, and the public to appreciate the extent and depths of rural poverty.