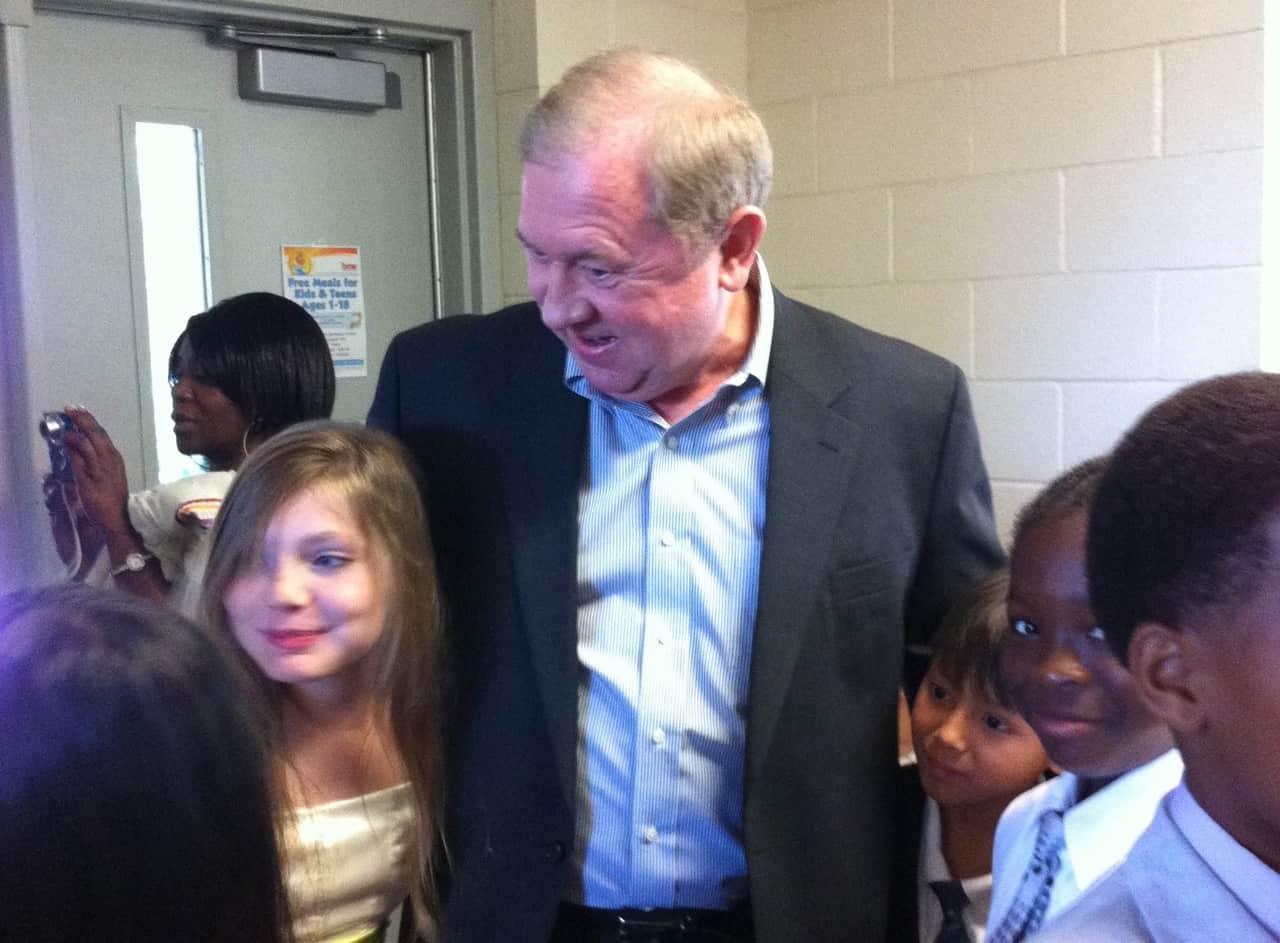

It was a pleasure to welcome the trustees of BEST NC to Shamrock Gardens Elementary, and to show off our school’s many accomplishments. We’re delighted they were impressed with our school and its wonderful staff.

In her recent account of Shamrock’s “blueprint” for innovation, however, BEST NC president Brenda Berg left out a critical piece of the foundation. She focused on the school’s “core business principles,” which she described as “supporting developing employees, creating clear career paths for leaders, and adapting their delivery of services based on data to meet ever-changing needs.” Indeed, Shamrock has done these things and done them well.

But Shamrock’s long-term accomplishments, and the difference the school makes in its students’ lives, is inextricably linked to the success of a 12-year-old effort to reintegrate the school racially and economically. This endeavor has fostered increased parent involvement, student activities that reach beyond the narrow range of material measured by standardized tests, and the kind of supportive, joyful atmosphere that makes students want to learn and teachers want to stay.

This is a crucial concept for those who wish to improve struggling schools. A school is not a business — it is a community that reaches well beyond its walls. Building schools that reflect the society we want our children to live in is a more daunting task than simply reorganizing internal operations and monitoring test scores. But it is a necessary one.

So here is the story of how we built that community at Shamrock.

In 1997, when North Carolina began rating schools based on standardized test scores, Shamrock Gardens was one of the highest-poverty elementary schools in CMS. When that first set of ratings was released, it placed Shamrock as one of the fifteen lowest-performing schools in the entire state. A flurry of interventions followed — removing the principal, sending a state assistance team, offering bonuses for test score improvement, adding an extra week to the school’s schedule. They had limited effects.

Plaza-Midwood, the middle-class, largely white neighborhood where my husband and I lived, was assigned to Shamrock. But almost no one sent their children there. When the toddlers who filled our neighborhood streets reached school age, parents sought out magnet and private opportunities, or put their houses on the market and moved to neighborhoods assigned to higher-performing schools. In 2005, the year before our son Parker started kindergarten, more than 90 percent of Shamrock’s students qualified for free or reduced lunch. About 6 percent were white. Most of those were poor as well.

We did not want to join the exodus. But we also knew the school needed to change. It was a pleasant place to visit, with a friendly staff and kids who lit up when they saw visitors. Still, as at so many high-poverty schools, teachers constantly came and went. There were few extracurricular activities, and little intellectual spark. No one could remember the last time the fourth grade had made the standard pilgrimage to Raleigh to learn about state government. It was the embodiment of separate and unequal.

So we rolled up our sleeves. Working with our school board representative, with neighbors, and with CMS staff, we chose a strategy that deliberately diverged from prevailing efforts at school “reform,” which focused almost exclusively on raising standardized test scores. Rather, we followed the example of nearby Idlewild Elementary, which had successfully used a ramped-up “gifted” program to diversify its student body and invigorate instruction.

Convincing our neighbors to join us in this endeavor proved a tough sell. When Parker entered kindergarten in the fall of 2006, we were the only family in our circle of neighbors who made that choice. But the program got off to a fine start anyway. Our principal, Duane Wilson, had hired one of the best gifted coordinators in the system. There had always been plenty of smart kids at Shamrock — the teachers had just been too overwhelmed to give them many opportunities to shine. In six marvelous years, the number of white children in Parker’s advanced class ranged from zero to two, and there were years when he was the only child who paid for lunch.

Mr. Wilson, who had more than three decades of experience working in public schools, also knew that a key part of his job was looking after his teachers. If Shamrock did not become a place where teachers felt supported and appreciated in monetary and non-monetary ways, if the pressure to produce test score miracles was so great that the revolving door kept spinning, no improvement would last. Progress made one year would vanish the next, as teachers burned out or looked for jobs elsewhere.

Mr. Wilson knew what he was doing. When Parker entered kindergarten, Shamrock’s staff was dominated by newly hired first and second-year teachers. By the time he graduated, many were still at the school, and had matured into six and seven-year teachers at the top of their game. Careful attention to data and the craft of teaching, especially on the part of assistant principals Tangela Williams and Paula Rao, helped test score performance grow across the board, eventually freeing us from the federal sanctions that had dogged us for years.

As the school improved, more families from Plaza-Midwood and neighboring Country Club Heights began to join us. They pitched right in, supporting teachers and creating the kinds of extracurricular activities that families at better-off schools take for granted. One parent organized an extensive vegetable garden program. Another worked with our butterfly gardens to develop butterfly-raising activities for every grade. We formed a Science Olympiad team. We bought art supplies. We started clubs. We raised money to send the fourth grade to Raleigh for the first time in decades.

All of these activities were designed not just for the “advanced” students, but for the entire school. As events and programs created more volunteer opportunities, parents and grandparents from less-well-off families upped their volunteer time as well.

Like all schools, Shamrock still faces plenty of challenges. Tight budgets and growing numbers of struggling families make it a tough time to be in education. At a school like Shamrock, where families come from distinctly different economic strata, it’s a constant — though highly rewarding — endeavor to balance different perspectives and different levels of social and economic clout.

Our staff also has to contend with state-mandated, test-focused policies that include the misleading A-F grading system, the destructively stressful Read to Achieve legislation, and a persisting threat to use test scores to measure teacher quality, despite abundant evidence that such policies are neither accurate or effective. Such tactics continue to drive families and fine teachers out of public schools — particularly the ones that serve our state’s most vulnerable children.

But so far, Shamrock’s dedicated staff and parents have weathered these storms, and our students continue to thrive and grow.

Almost half a century ago, when Julius Chambers argued the Swann desegregation case before the Supreme Court, he contended that schools would only be equal if they all enrolled children from politically and economically powerful families, who would thus have a personal stake in making sure all schools succeeded. My years at Shamrock have made it clear to me that he was right.

Not every struggling, high-poverty school is fortunate enough to sit near a well-off neighborhood. But along with promoting investment in teaching and learning, organizations such as BEST NC need to look beyond their business-oriented strategies and seize every opportunity to champion racial and economic integration — leading by personal example when possible. Separate wasn’t equal during the era of Jim Crow. It isn’t equal today either, and no effort focused solely on the classroom will make it so.