The North Carolina Court of Appeals held on Tuesday that the General Assembly cannot take career status away from teachers who already have earned it. That’s the main takeaway from a 57-page decision. But there’s much more to the NCAE v. State opinion and much more in implications for North Carolina.

But first, I should note that I am not an uninterested bystander on this issue. I was general counsel for the North Carolina Association of Educators when the General Assembly passed the career status repeal law as a part of budget bill in 2013 and when the NCAE filed a lawsuit in response. I also am not an uninterested bystander because I’ve worked on employment issues for all parties over my career — teachers, principals, superintendents, and school boards — and fair, effective employment processes matter to all.

This leads to the first remarkable aspect of this opinion. One might imagine that a case involving whether or not teachers have a constitutional right to retain certain due process protections would pit teachers against school districts. It didn’t happen here. Instead, the court noted that school districts also benefited from career status. Judge Linda Stephens, writing for the 2-1 majority, stated:

Furthermore, Plaintiffs submitted affidavits from eight North Carolina public school administrators, who each confirmed that the Career Status Law is an asset for attracting and retaining quality teachers to serve in our State’s public schools; that the four-year probationary period provides more than adequate time for school districts to evaluate teachers, identify performance issues early, provide constructive feedback for improvement, and make informed decisions that ensure career status is only granted to teachers who have proven their effectiveness; and, most importantly, that the Career Status Law effectively provided school administrators with sufficient tools to discipline and/or dismiss teachers who have already earned career status and thus did not impede their ability to remove such teachers for inadequate performance.

By contrast, the Court of Appeals found the State’s argument that career status got in the way of getting rid of ineffective teachers unpersuasive:

Yet the only support that the State’s affidavits offer for this premise consists of vague and sweeping generalizations about tenure as an abstract concept, rather than specific facts regarding the operation of North Carolina’s Career Status Law or its allegedly adverse impact on our public schools.

For moving forward as a State, this provides an important framing of the issue. Providing reasonable due process protections isn’t the problem. School districts and teachers can continue to work together to make sure the right tools are in place for professional growth as well as for making difficult employment decisions. And as the court noted, career status can continue to be refined in the law as needed:

[T]he record is replete with evidence of less drastic available alternatives. The legislative history of the Career Status Law demonstrates that its provisions have been amended numerous times over the last four decades … If it had been truly necessary to further augment the ability of local school boards to dismiss teachers for performance-related reasons, our General Assembly could have done so through further reforms; indeed, Plaintiffs’ affidavit from Rep. Glazier clearly demonstrates that there was a less drastic alternative available here in the form of H.B. 719, which would have “added definitions of teacher performance evaluation standards, teacher performance ratings, and teacher status, thus creating greater consistency in the determination of career status and revocation of career status based on evaluation ratings,” an alternative which enjoyed nearly unanimous bipartisan support.

For early career teachers, this ruling does not apply. The Court of Appeals held that teachers in the pipeline for career status do not have constitutional rights to continue on that path. In making this holding, the court noted:

we empathize with the thousands of other similarly situated probationary teachers across this State who no doubt share his [plaintiff Brian Link’s] skepticism regarding the wisdom of legislation that purports to enhance the educational experience of our State’s public school children by essentially yanking the rug out from beneath the feet of those most directly responsible for educating those children in a manner that experienced educators have warned will make it more difficult for North Carolina school districts to attract and retain quality teachers in the future. Nevertheless, this Court may not substitute its views for those of our General Assembly, and we are bound by the aforementioned precedents from our Supreme Court.

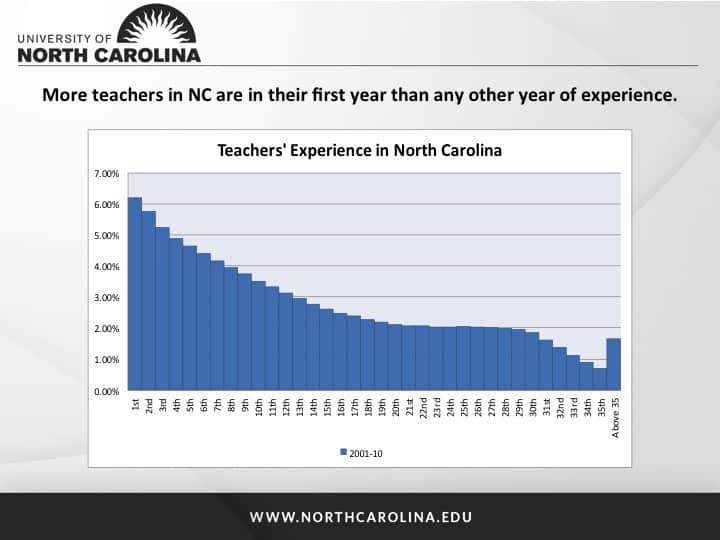

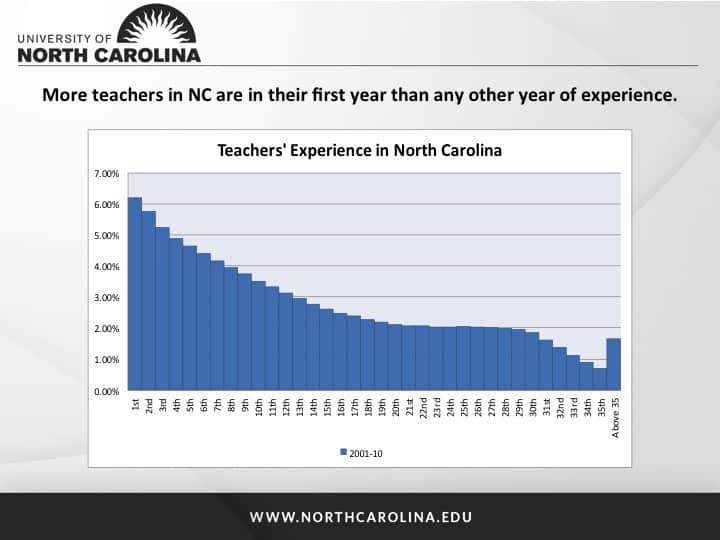

As a result, teachers who do not have career status will be employed on one-year contracts until 2018 and then will be offered one-, two- or four-year contracts. As North Carolina faces a “greening” of the teacher workforce, we will have substantial numbers of teachers employed by contract. Consider this: nationally in 1988, the most common number of years of experience of teachers was 15 years of experience. Nationally this has shifted to a younger workforce. By our most recently available data, in North Carolina more teachers are in their first year of teaching than any other number of years of experience.

Bastian, Kevin C., & Patterson, K.M. (2014) Teacher Preparation and Performance in North Carolina Public Schools.

We know that it is extremely important to have in place plans for addressing teacher quality and retention with early career teachers. It also will be important to consider reasonable due process protections for these teachers.

And here is where Judge Dillon’s dissent is important. Judge Dillon parts company from the majority on the holding that career status was constitutionally protected for teachers who already had earned it. He instead focuses on the lack of a right to a hearing for teachers under the new contract system. Judge Dillon states:

Therefore, I conclude that N.C. Gen. Stat. § 115C-325.3(e) (2013) – which is part of the Career Status Repeal – is unconstitutional in that it does not provide a career teacher the right to a hearing before a local school board may act on a decision not to retain the teacher, but rather grants a local school board the discretion whether to conduct a hearing.

This lack of protection for a hearing applies for all teachers on contract. By contrast, school administrators, if there is a recommendation for not renewing the employment contract, have a right to hearing. This concern for basic fairness is consistent with another opinion Judge Dillon authored on the standard applied for nonrenewal decisions. In writing the 3-0 opinion for Joyner v. Perquimans County Board of Education (2013), he states:

However, given that the record fails to disclose a rational basis for the Board’s decision in the present case, the scant nature of the Board’s two findings – that the Board had “concerns” about Petitioner’s performance and that the Board could find a teacher “to do a better job” than Petitioner – serve only to bolster the superior court’s conclusion that the Board’s decision was arbitrary and capricious. To accept the Board’s “findings” as explaining a valid basis for its decision – or, put another way, as indicative of the standard for attaining tenure status, without being accompanied by an articulation of a specific concern supported by substantial evidence in the record – would be to grant the Board unfettered discretion to act arbitrarily toward a particular candidate, as there will always be some candidate, somewhere, who could “do a better job.”

Perhaps the State will pay attention to this dissent and fix the hearing rights for all teachers on contracts. Or again, teachers, school administrators, and boards can work together to find reasonable approaches.

I have focused so far on the impact of the decision. But let’s return to the heart of the issue – that career status raises constitutional concerns and it is the role of courts to review constitutional challenges. The court observes that “the State characterizes the present lawsuit as the sort of partisan policy dispute that is for the people’s elected representatives, rather than the courts, to resolve.” But it is not. The specific constitutional challenges in this case were whether the career status repeal law violates the Contract Clause of the United States Constitution and the Law of the Land Clause of the North Carolina Constitution. The court relied on prior court opinions – precedence – to make its findings in very clear terms.

In finding that the career status repeal violated the Contract Clause, the court states:

We consequently conclude that our Supreme Court’s consistent pattern of refusing to allow the State to renege on its statutory promises, after decades of representing the valuable employment benefits conferred by those statutes as inducements to public employment, supports, and even compels, the result we reach here.

In finding that the career status repeal violated the Law of the Land Clause, the court refers back to the 1998 North Carolina Supreme Court decision, Bailey v. State, on employee retirement benefits. The court states:

Here, as in Bailey, Plaintiffs contracted, as consideration for their employment, that after fulfilling the Career Status Law’s requirements, they would be entitled to career status protections. Here, as in Bailey, the Career Status Repeal purports to abrogate those protections and thus constitutes a taking of Plaintiffs’ private property. Here, as in Bailey, the Career Status Repeal offers no compensation for this taking. Thus, here, as in Bailey, the Career Status Repeal violates the Law of the Land Clause.

This opinion is rigorous in its application of precedent which is a reminder that, indeed, these are constitutional issues, not partisan issues. It also is a reminder that this opinion may be appealed to the North Carolina Supreme Court. If the State appeals, then there will be a final resolution of the constitutional dispute. While we watch for this possible last step in the court process, we can turn our primary attention at the state and local level to making sure we have all pieces in place for providing a quality teacher in every classroom in North Carolina.