Editor’s note: This post originally appeared on Bit & Grain.

Leslie Locklear: I was born and raised under the tall pines of Hoke County. With a mother from the Waccamaw Siouan and Coharie tribes and a father from the Lumbee tribe, my blood itself is a beautiful blend of inter-tribal history. Though my identity as an Indigenous student was always present within the study body population, navigating the story of who I was within the classroom was often extremely difficult. In the curriculum, in the text, in the stories, in the classroom, I didn’t exist. I first heard my tribal nation mentioned in the classroom during Mr. Cooper’s American Indian Studies class in 12th grade. As he delved into our history, our ancestors, our story as a tribal nation, I finally began to find my place both, physically and figuratively, in school.

Meredith McCoy: My father is a citizen of the Turtle Mountain Band of Chippewa Indians (Anishinaabe) and my mother’s family is of Scottish, English, and German descent. I was born in Durham and grew up in Chapel Hill. Chapel Hill-Carrboro City Schools were highly diverse in the 1990s and early 2000s, and my teachers often tried to incorporate the many backgrounds and experiences of their students into the curriculum. Like Leslie, I brought my identity with me into the classroom, but knowing how to explain it to teachers and classmates who had little exposure to Native communities was often difficult. Much of the curriculum seemed set to teach me that Native people were somehow lesser than white people, and nothing mentioned the ongoing presence, power, and diversity of Native nations. Ms. Gilchrist, my fourth grade teacher, and Mr. Hennessee, my eighth grade Social Studies Teacher, were two educators who actively bucked that trend. In their classrooms, Native American history – my history – wasn’t a footnote relegated to the first chapter of the textbook.

As storytellers, educators and Indigenous women, we find critical importance in sharing our story and our history. Many years after graduating from high school, we find this Maya Angelou quote rings truer than ever: “I’ve learned that people will forget what you said, people will forget what you did, but people will never forget how you made them feel.” We remember the educators who made us feel that our Native identities were assets that could help us achieve in life and school, not deficits we had to overcome. These educators helped us find our place in the classroom and influenced our decisions to become educators ourselves. These teachers helped to foster our identity and launch us into self-exploration. They are educators who built critical relationships that we maintain many years later. They are educators who, in all definitive terms, changed our lives.

Carla Gilchrist, Meredith’s 4th Grade Teacher

Ms. Gilchrist grew up in Durham where she attended all-black schools. Thinking back on her experiences in Durham, she recalls, “I was able to learn, I think, a lot about history and about how fascinating it was, and I saw myself. I think because I was afforded that kind of education, that was the kind of education I wanted for my students. I was blessed to sort of be able to see myself in history and for it to be revealed to me in a way that didn’t make me feel ashamed or like being black was something to be ashamed of. So I never wanted to present history to children in a way that would make them feel ashamed of being who they were.”

Ms. Gilchrist’s focus on making sure students see themselves in their curriculum extends to Native students, and she believes that teaching Native history is central to helping students understand America. She often incorporates references to tribal communities from across North Carolina when teaching about language, geography, and political history. Most of my previous teachers had limited their discussion of Native people to rosy depictions of Thanksgiving or Columbus, but she was the first teacher I heard openly discuss settler colonialism. Ms. Gilchrist discussed the complicated history of colonization, allowing us to consider the negative impacts of colonialism and the resilience of Native communities. Her class projects gave me space to learn about my own community’s history and culture.

Ms. Gilchrist believes that it’s important to engage in open discussions of identity and race with young students, and finds that talking about her own identity and life experiences helps her students learn ways to talk and think about their own racial identities and cultural backgrounds. She explained, “As a teacher when you discuss race, you give permission to children to talk about race. And so, once you do that, you’ve opened a discussion that becomes richer. … [Once they’ve learned] that it’s actually ok to talk about race, they can ask questions.”

Each year at Glenwood Elementary, the school held a multicultural fair. Each class focused on a different country, and students learned about that country’s languages, foods, geography, and music. When I was in her class, Ms. Gilchrist adapted this annual fair to let our class focus on Native American history. By giving me space to publicly discuss and acknowledge my identity, she sent a message that my Indigeneity had value in academic and public spaces. In so doing, she helped me build the confidence to bring identity-related topics into my coursework during middle school, high school, college (where I minored in Native American Studies), and into my own classroom when I became an educator.

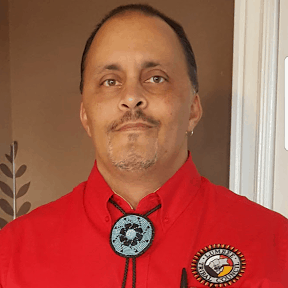

Frank Cooper, Leslie’s 12th Grade American Indian Studies Teacher

Mr. Cooper never intended to be an educator, but as he says, this “is where the Creator put me.” He stumbled into teaching because he needed to “always have an answer for people who had questions.”

As a member of the Lumbee tribe, he is no stranger to questions. He spent his adolescence in High Point, North Carolina, where he was one of 27 American Indian students at High Point Central High School in a student body of over 1,200. He, remembers that “identity was a constant battle.” Internal and external questions about his multicultural background and the complicated history of East-Coast Indigenous population inspired his lifelong quest to learn about his culture and people.

Mr. Cooper’s classroom was a design laboratory for my identity. He strove to connect the curriculum to our life experiences and I remember when first he asked me, “Leslie, where did your last name come from?” I had no idea. Locklear is a name that identifies many members of the Lumbee tribe, and its history contains the timeline of my people and connects me to the tribes who form the backbone of my identity as an Indigenous woman. I started plugging in all the missing pieces of my family and tribal history that had been left out of the history books through a genealogy project in his class.

Mr. Cooper’s classroom was a design laboratory for my identity. He strove to connect the curriculum to our life experiences and I remember when first he asked me, “Leslie, where did your last name come from?” I had no idea. Locklear is a name that identifies many members of the Lumbee tribe, and its history contains the timeline of my people and connects me to the tribes who form the backbone of my identity as an Indigenous woman. I started plugging in all the missing pieces of my family and tribal history that had been left out of the history books through a genealogy project in his class.

His passion for history made me feel like every morsel of knowledge was essential to know. When questions like “How many tribes are there in North Carolina?” were met with blank stares and confusion, his response was often, “Tell me tomorrow.” I never felt discouraged or scolded for not knowing, and I learned how to research and find answers on my own. Mr. Cooper taught me to seek out answers, a skill that’s inspired many years of research about my people and my identity.

Chuck Hennessee, Meredith’s 8th grade Social Studies Teacher

For me and the leagues of former volleyball team players that he coached, Chuck Hennessee will forever be “Coach.” Coach knew that his middle schoolers needed space and support to explore the world around us and how we fit into it. We also needed affirmation that our identities were welcome in the classroom and added value to our school experiences. Coach Hennessee talked about Native communities from an asset-based perspective. Rather than relegating Native peoples to past-tense discussions of hunter-gatherers, Coach talked about the strength, resilience, and creativity of Native people. He believed that “We really cheat the students if we don’t get them to understand that there are clear and very strong histories that are within our Indigenous population.” Like Ms. Gilchrist, Coach incorporated the ongoing achievements and contributions of Native people into the curriculum.

Coach also believed that culturally responsive teaching is teaching that meets every student where they are and engages each student’s background and identity. In his Social Studies classroom, he used humor and individualized projects to help students connect to North Carolina history. One of these projects, a family history research project, forever changed my understanding of myself as a biracial Native and white person. The project equipped me and other students with the tools to investigate our families more fully, to ask questions and record the information we found, and to develop a keen understanding of where our stories fit into both the history of North Carolina and of America. Coach described this project as “an attempt to draw every student in so that they had a better understanding of who they were, because if you don’t know where you’ve been then you will not know where you’re going,” noting that “It’s one thing to teach kids history, but then to get them to see ethnically where they fall into that is what their history is.”

Warm, Safe Spaces to Learn

Ms. Gilchrist, Mr. Cooper, and Mr. Hennessee made us feel represented and welcome in the classroom. By affirming our identities at school, they assured us that we belonged in academic spaces and that our cultures were assets to celebrate, not deficits to overcome. As Ms. Gilchrist notes, when teaching happens in a culturally relevant, inclusive way, “You’ve created a space where a child’s like, ‘This is where I’m supposed to be.’ You have to create those spaces, which means you have to know who your kids are.” Mr. Cooper describes treating all students as though they were his own kids. In thinking of his classroom, he says, “I just try to make everybody relevant and I try to make them feel like, you know, I care. I do care, but I try to make them understand I care and feel it. Cause once a child is convinced of that, 9 out of 10 times, they’re gonna do what they need to do. And that’s the way you have to treat them. I treat my students like they’re mine.”

Our teachers put us in the driver’s seat of learning about our families, our histories, and our communities. They fostered a safe exploratory environment for their students, one that was forged on the strength of relationships between the educator and the student. In the classroom, they made it clear that we didn’t have to have all the answers yet, but that we could develop the tools to begin a lifelong process of thinking and learning about our country’s complex history and our place in it. We learned that each of us had a place in the classroom, and that our families were important to the history, present, and future of North Carolina.

As Mr. Cooper says, “The key is care.”