Cameras followed 22-year-old Bertie resident Davonte Harrell, also known as Dada, through the intimate moments of his teenage years — on prom night, during fights with his parents, while spending time with his friends or his girlfriend.

“I don’t know why I did it because I was never the type to just jump out there and do stuff,” Harrell said. “But I was like, ‘Sure,’ and it clicked, just like that.”

Harrell said his comfort came from a close relationship with the Raising Bertie filmmakers — director Margaret Byrne, director of photography Jon Stuyvesant, and producer Ian Kibbe. They followed Harrell and two other young men from Bertie — Reginald Askew (Junior) and David Perry (Bud) — for several years, capturing their stories. At school, at home, in their social lives, and in between, Raising Bertie gives a candid glimpse into their personalities, dreams, and struggles.

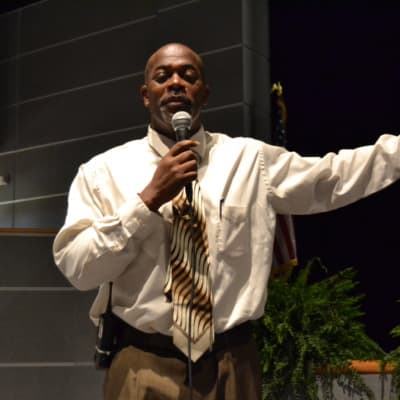

School board members, teachers, administrators, and community members watched the documentary in the auditorium of Bertie High School on August 24 alongside Byrne, Stuyvesant, Kibbe, and Harrell. Askew and Perry could not attend because of work.

The quality of education in Bertie schools, economic opportunity for graduates, and the socioeconomic forces that play into young people’s ability to succeed were intertwined with the boys’ individual narratives. The hope of the viewing was to create a dialogue among community leaders around these issues — ones that are both specific to Bertie and present across the state and country.

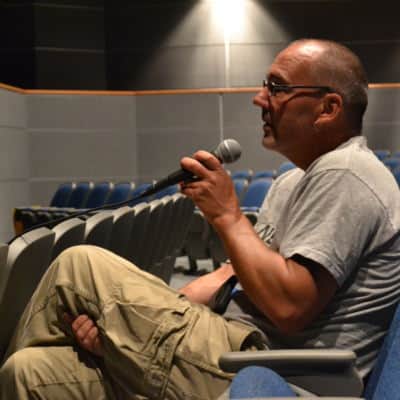

“The question becomes, how do we broaden this discussion?,” Yolana Burwell, senior fellow at the NC Rural Center, asked the audience. Burwell facilitated the panel and invited anyone to come forward, react to the film, and share suggestions to address the underlying problems.

Bertie is one of the poorest counties in North Carolina. According to 2010 census data, the county’s median household income was $29,388, compared to the statewide median income of $46,693. Only 11 percent of residents 25 years or older had at least a bachelor’s degree, compared to 27.8 percent statewide.

There was an overwhelmingly positive response from those who spoke up. All encouraged the audience to confront the issues at hand to make sure Bertie’s youth feel supported. A sheriff applauded the raw quality of the film. An 85-year-old resident warned against division. A teacher of over 20 years suggested showing the film to state leaders to reveal the realities of this section of the state.

Forms were passed around asking attendants how they felt they could help in supporting Bertie’s youth. Many people expressed interest in having a public viewing in the community, where anyone interested could watch the documentary for free.

Kibbe, the producer, said getting the film out to the community at large and to a statewide and national audience — and sparking conversation and change — is integral. He spoke on the importance of telling the stories of young black males, and how he hoped the film could help viewers in similar and different atmospheres connect and relate. Already, Kibbe said, they’ve shown the film in urban and rural places. He said there have been connections drawn no matter the setting.

“Closing the empathy gap was a big goal of ours for rural communities, and for young people, particularly people of color,” Kibbe said. “These aren’t stories that you see often.”

The filmmakers originally showed up to Bertie for a six-minute video project, said Stuyvesant. That’s when they were introduced to The Hive — Bertie County’s only anti-poverty organization that serves as a food bank, after-school center, community kitchen, and job center. In 2009, The Hive became an alternative school for at-risk youth.

Stuyvesant and Bryne met with Vivian Saunders, founder and director of The Hive, and the boys, who were attending the school at the time.

“Within like three or four days, we were like, ‘Whoa, this story is much bigger than what we’re seeing,'” Stuyvesant said. “We, basically, at that point, promised them we’d come back and start making a feature-length documentary.”

At that point, no one knew that would mean six years of relationship-building, collaboration, and storytelling. But it did.

The Hive is a focal point of Raising Bertie. Askew, Perry, and Harrell felt at home in a way that they didn’t in traditional public schools. Harrell said the main difference for him was that, “They cared.” He said he felt pushed aside in public school just because he didn’t catch on to material as quickly as others. The film documents the boys’ experiences after the school was shut down.

Tundra Woolard, who is the NC Pre-K director at Bertie County Public Schools, has worked in the county for 17 years, and, as a former teacher, said she has seen the struggles of black males specifically. Woolard said the film opens up a conversation about looking past test scores and focusing on what individualized learning can do for students.

“With all children, I know the importance of understanding where they come from, their family life, their routines,” Woolard said. “I think that is very important for us to understand so that we can serve individuals instead of just thinking everybody is this cookie-cutter, so to speak.”

The movie ended without tidy wrap-ups. Askew was preparing for a new baby with his girlfriend. Perry was working. Harrell was graduating high school with dreams to be a barber. During the panel, one audience member asked Harrell what the community could do to help him in his own life.

After at first saying he didn’t want to talk about it, Harrell responded that he just didn’t see any job opportunities in his field.

“I want you to also understand that folks are listening and want to back you up,” Burwell told him. Harrell thanked everyone for showing up, and for their support.

“We got your back,” a man shouted from the audience.

Recommended reading