Dear Miles,

My experiences as an education administrator in North Carolina have been primarily with students who are poor, minority, and struggle academically. I wonder day in and day out about the relationship between education outcomes and socio-economic status (SES). Education research has found home background to be an important determinant of educational outcomes, and economic research has shown that education strongly affects earning potential.

According to the US Census Bureau, North Carolina had an estimated population of 9,943,964 in 2014 with 17.5 percent of persons below poverty level.

Of the students in poverty who live in Wake County, I have the opportunity to work with two types.

The first type of student has the raw intelligence that allows them to achieve satisfactory outcomes in school despite home and life circumstances. The second type of student needs assistance to produce satisfactory outcomes in school along with assistance in dealing with home and life circumstances.

Poverty

Poverty impacts the home life and school experience of my students. The home background of my students is the most important factor influencing educational outcomes. Student poverty is strongly related with a range of concepts including parental educational attainment, household income levels, and access to basic needs.

The history of America is filled with examples of people who grew up in poverty and yet managed to defeat its strong grip.

Many poor students defeat the odds and do well in formal learning environments. But many don’t.

As educators, we need to learn to teach with poverty in mind. Chronic exposure to poverty changes our students and their brains. In Eric Jensen’s Teaching with Poverty in Mind, he identifies for educators the factors affecting academic success so that poor students can experience “emotional, social, and academic success.”

The Odds

Many racial and ethnic groups in post-industrialized America strived to exceed the educational levels of previous generations. For African Americans, structural limitations often prevented formal education.

However, there is always a story of a grandmother, father, or mother who campaigned for their children to take learning seriously. Conversations and family priorities were centered around learning and attaining formal and informal educational opportunities.

Education was seen as a critical vehicle for African Americans to exit generational poverty.

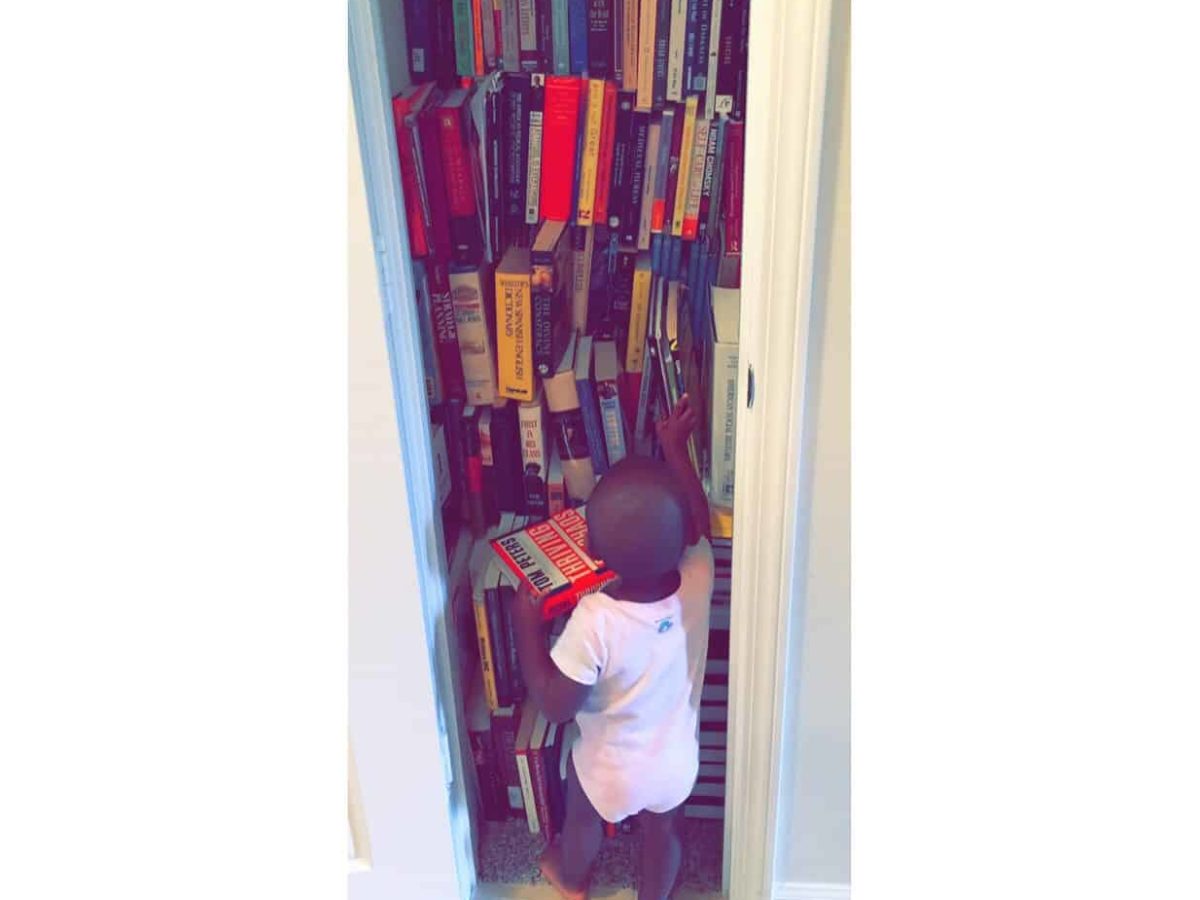

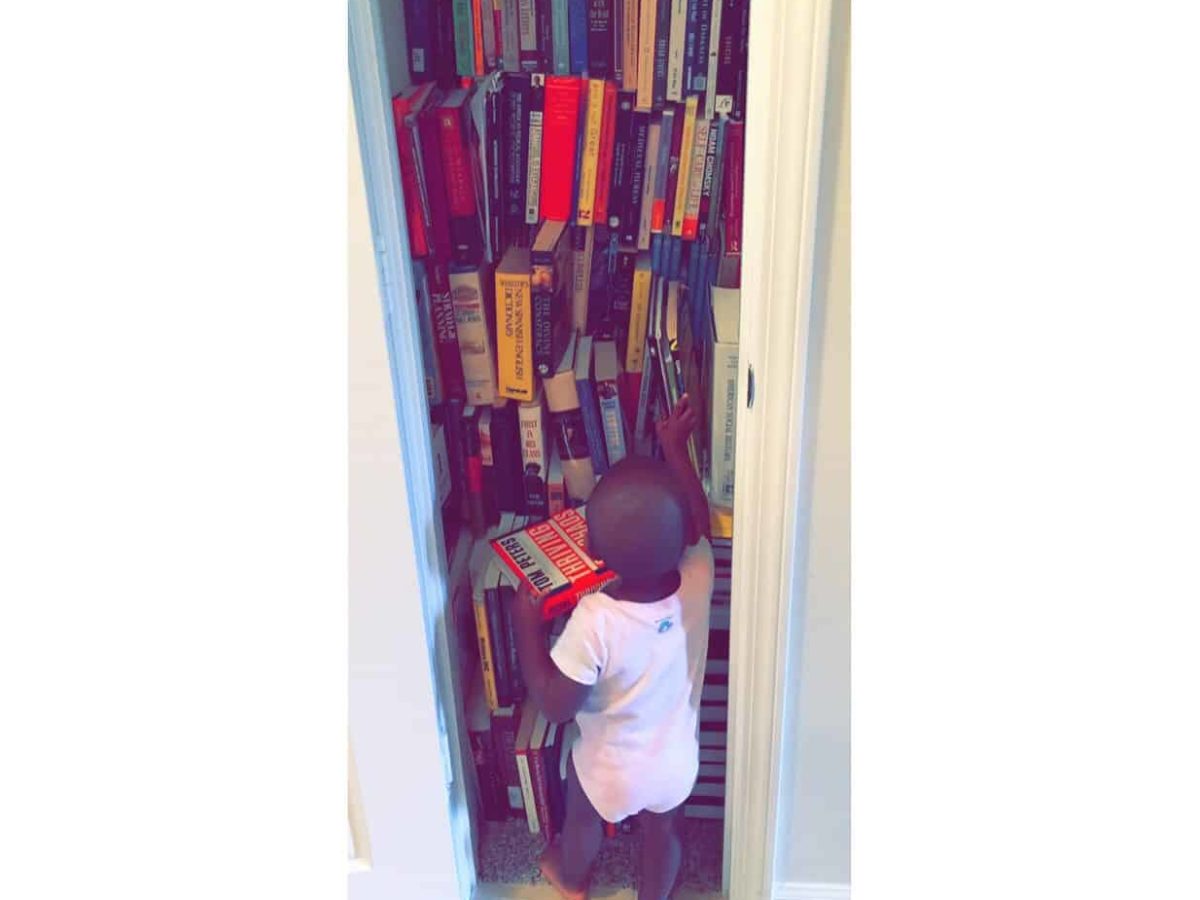

Black parents applied pressure at home through homework, reading, etc. to reinforce the value of learning.

In my experience, the parents themselves often were not educated enough to actually understand the materials that their children were learning at school. So, the parent support came from instilling the value of formal and informal education and encouraging their children even though the parent could not complete the school work themselves.

We, as educators, need to challenge any assumption that poverty guarantees academic failure for our students. We, as parents and the community, must encourage our students to beat the odds!

Fighting Fate

When a new student enters my office, it is always difficult to hear the circumstances of his or her home life, knowing that the research suggests that the student has a very little chance of succeeding in school.

Often I feel like I am fighting fate. I know the odds are stacked against them.

The worse part? So do they.

A home life for my students may include a single/uneducated mother or father, criminal records for the parents and/or student, living in a poor neighborhood, and living below poverty level without access to enough or healthy food. You know the statistics for these students.

Nevertheless, every year my team is surprised by amazing students. There is always at least one who still possesses a fierce determination to succeed.

“Christian, You Can Do Anything”

I ran into a friend of mine, Ventura, recently. He is a middle-aged Hispanic who works as a janitor with his wife at a local school. He logs in 80 hours a week working two janitorial jobs. We often talk about our sons and our experiences of fatherhood.

Because of his journey as a foreign-born, poor father in America, Ventura dreams for his sons to be successful.

He did not go to college and actually no one in his family ever went to college. When his son, Christian, was born, Ventura would tell him,

“You can do anything.”

He taught Christian not to view life through its limitations but through its opportunities.

In the 9th grade, Christian told his dad that he wanted to go to Duke University, but that he knew it was too expensive for his parents. Ventura told his son that nothing is out of reach. Ventura said, “Christian, you can do anything, including going to Duke University.”

Knowing that Duke was very expensive, Ventura and his wife decided that if it was necessary they would sell their car and their home for Christian to go to college.

Christian is just in the 11th grade, but his SAT scores were high enough that he has been offered an opportunity to one of Duke’s undergraduate programs once he graduates high school. This is potentially a family-altering opportunity that will ripple back through generations of their struggle with poverty and will redefine their future. Christian is beating the odds.

Miles, you can do anything…

Your Dad

Here are the other letters in this series exploring how to change the trajectory of black men in North Carolina.