I was in the 10th grade at Olathe Northwest High School when one day, my English teacher Mr. Anderson was going around the classroom asking all of us what we wanted to do when we grew up. I told him I had an inkling to be an English teacher but was quick to note that it wasn’t because of him. (It was because of him, but I wasn’t going to boost his ego.) Not long after, I realized that I would never survive as an English teacher. To this day, I still cannot tell you what an adverb is.

Growing up, I was in high-level math classes; it was pure bliss solving problems that had concrete answers. I was either right or wrong and nothing was left up for interpretation. Time went on and by my senior year, I had officially decided that I was going to dedicate my life to being a math teacher.

Fast forward four years. I landed my first job as an eighth grade math teacher, and I could not have been more excited. I loved my first year of teaching, but it definitely took a toll on me. At one point I was drinking a two-liter bottle of soda every day just to stay awake. The student teaching experience just does not do the real thing any justice.

I loved my first job; I had great kids, phenomenal coworkers, and a strong community. But in true millennial fashion, I decided that there were bigger and better things outside of Kansas. So on a whim, I moved to the Southeast to satisfy my wanderlust.

At the end of my 3rd year of teaching, things took a turn for the worse: I was at my wit’s end, ready to throw in the towel. I started looking into other options like graduate school. I even made a Linkedin profile, hoping someone was desperate enough to hire me. With no luck and in a panic to pay the bills, I began searching for a different teaching job.

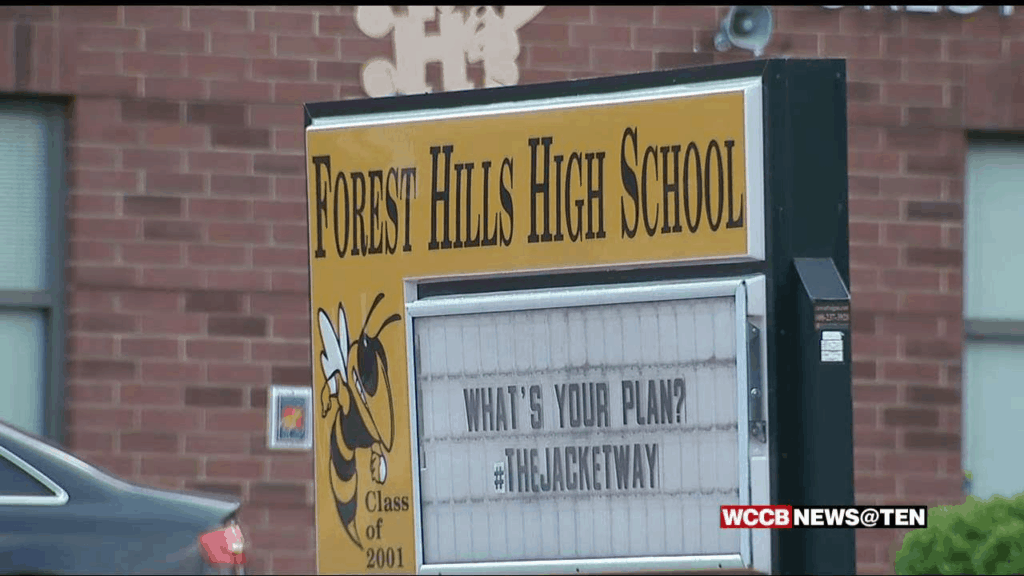

When I arrived at Forest Hills High School, I had no idea what I was getting myself into. For the first three years of my career, my best practice was teaching straight out of a textbook. But who could blame me? That is how I grew up, and that’s how I was taught to teach in college. So I had this, “If I learned out of a textbook, then you will too!” attitude.

I was in for a surprise when I arrived at Forest Hills; they did not have any math textbooks. I could feel my stomach drop to my toes. What was I going to do? I was comfortable in my own style of teaching and now I was practically being forced into the alternative. I honestly was not sure if I could survive this, but luckily I was surrounded by a group of people who knew what they were doing and were on a mission to provide an equitable education for all students.

Forest Hills High School is a Title I school located in Marshville, North Carolina with 68.1 percent economically disadvantaged students. Our department chair, Lauren Baucom (@LBmathemagician), inspired us to redefine math education so that we could provide an equitable education to all of our students.

In one year’s time, we were able to achieve 16.5 percent growth on our Math 1 EOC scores. Most schools grow on average two or three percent every year, so this was a huge victory for us! But this growth didn’t just come to us; we worked hard every day and we made some major changes within our department so that equity was at the top of the priority list.

As a department, we made the bold decision to offer high-leveled content to all of our students, despite the label of the class. For example, our standards classes and our honors classes were both exposed to the same high-level content; the standards content was not restricted just because it was a standards class and in the honors classes we didn’t just blow by the fundamentals under the assumption that honors students knew basic math. We chose to set the bar high and expose all students to rich and engaging mathematical content. This approach called for an abundance of differentiated instruction and personalized learning, but we believed this was the most equitable practice for our students success.

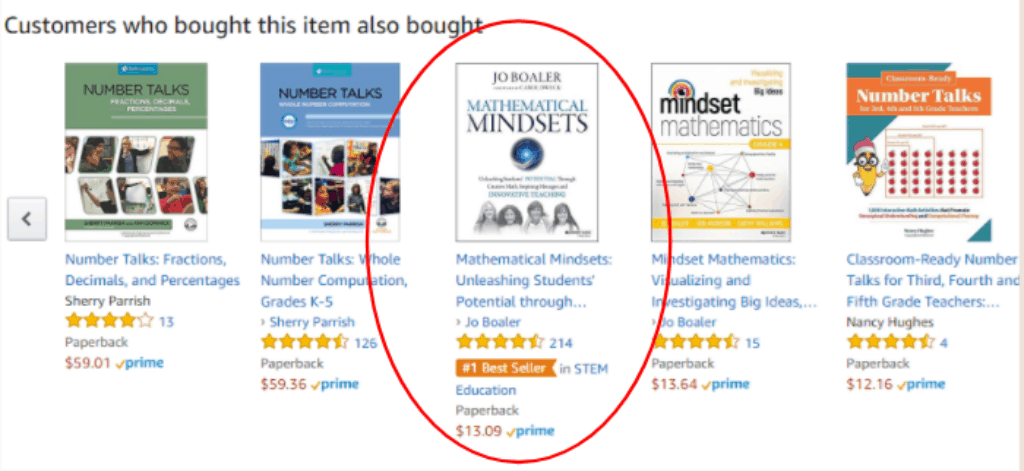

Last summer, I was browsing Amazon for who knows what and something caught my eye. Down at the bottom where Amazon sucks you into their “suggested items” traps was a book called “Mathematical Mindsets”. On a whim, I ordered the book and it arrived two days later. I started reading and could not put the book down. It spoke to everything I had just experienced at Forest Hills. The book dives into best mathematical practices, assessments, and the obvious; growth mindset. The author had me hanging on to every last word. But none hit home more than the chapter on tracking.

A quick refresher: tracking is the practice of grouping kids into leveled classes based on their current ability level. Think honors, standard, and intro. This is pretty common practice across the United States; in fact, most of us probably grew up in a “performance system” like such.

In the book, there was a particular story about the San Francisco Unified School District (SFUSD) and their unconventional approach to tracking that I kept going back to, wanting to know more. I wasn’t getting all the answers I wanted so I picked up the phone and called the math supervisor, Lizzy Hull-Barnes, and talked with her more in depth about what really was going on at SFUSD.

Here is what I learned:

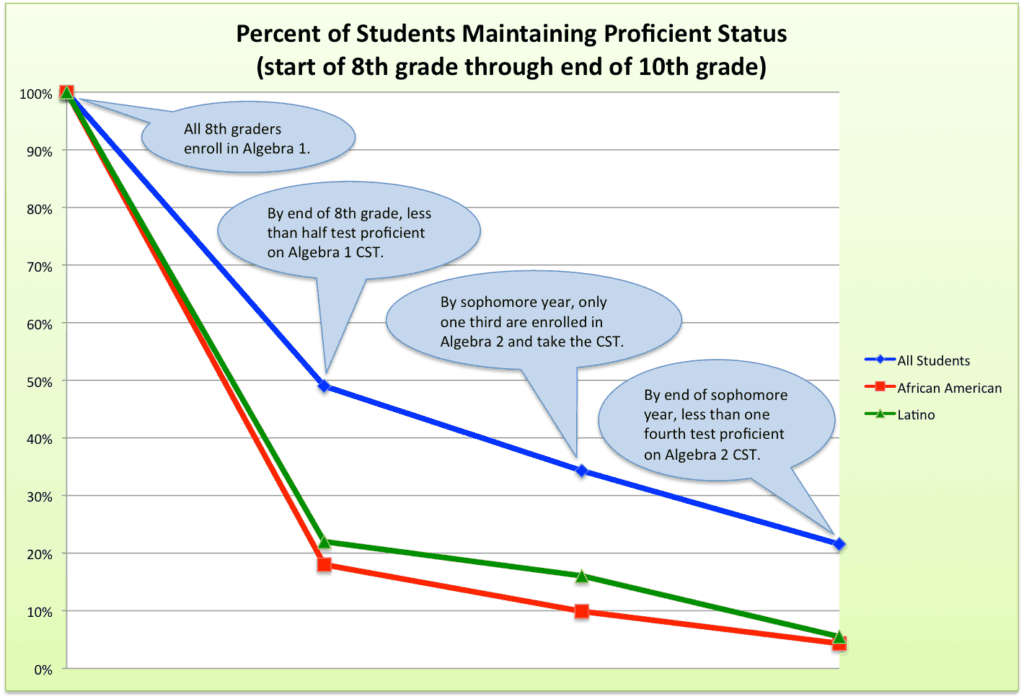

Since 2014, the district has “detracked” their mathematics courses up until 11th grade. They did so in response to severe declines in proficiency scores on state tests across all grade levels which were leading to high retention rates. For example, of the eighth graders taking Algebra I in the tracked system, a whopping 40 percent of them were being retained the next year.

So SFUSD put their foot down. Enough was enough. They deconstructed their math course sequence so that students would be heterogeneously grouped up until the 11th grade. This change allowed students the opportunity to learn grade-level mathematics deeply and have it be developmentally appropriate.

Just one year after detracking, the retention rate dropped from 40 percent to eight percent in one year, and their proficiency scores have steadily increased every year since.

That’s not even the best part.

When SFUSD detracked their mathematics courses, they began to see an increase in the number of students taking higher level classes — particularly the number of minority students. Their approach addressed what I like to call an “opportunity gap” — the divide which is created when we place students according to perceived ability levels.

Traditionally, in a tracking system, we use scores and a teacher recommendation to place students in what we deem “appropriate classes.” This process can start as early as sixth grade, which means teachers are making life-changing decisions on behalf of 11-year-olds.

The indicator that gets the most consideration is the teacher recommendation. Does this shock you? We spend 180 solid days with these kids; of course we know what is best for our students. But if that’s the case, then why are students who score fours and fives on their state exams being recommended and tracked into lower level classes? This happens more often than you probably realize.

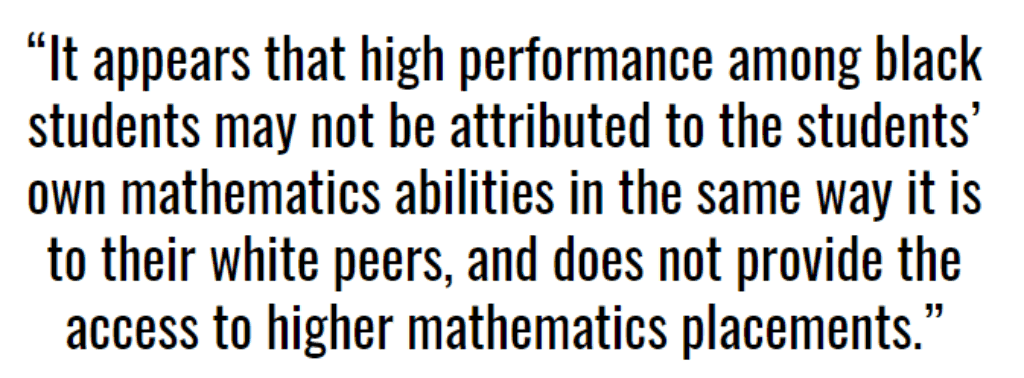

In a 2010 study conducted by professors at North Carolina State University, more than 2,900 eighth grade students of all racial backgrounds were monitored to better understand how students were tracked in mathematics courses. What they found was heartbreaking. For white students, the mathematical performance indicator was taken into consideration by almost double of that of the teacher recommendation. For black students, math performance and teacher recommendation weighed equally. Part of the study’s conclusion reads, “it appears that high performance among Black students may not be attributed to the students’ own mathematics abilities in the same way it is to their White peers and does not provide the access to higher mathematics placements.”

And this is important because in today’s world, if a child wants to go into a STEM-related field in college, they must have calculus or statistics prior to admission. San Francisco recognized this inequity and because of their “detracking” policy, all students now have the opportunity to take high level classes.

But in a tracked system, low-tracked students will most likely never have the opportunity to take these classes because of decision we made when they were 11. If we have children that are being denied the opportunity to take higher level mathematics courses, then we are shooting ourselves in the foot.

Not too long ago, Amazon considered making Charlotte home to their second headquarters, bringing more than 50,000 jobs and $5 billion in investments. But sadly, our beautiful city didn’t make the cut. Amazon claims this was due in part to Charlotte’s lack of qualified tech workers: only about 47,000, half of what other bidding cities could supply. So it begs the question: Can we be doing better not only for our kids, but for our city?

I know we cannot detrack our education system overnight. But there are steps we can take right now to better our classrooms and to provide an equitable opportunity for all students to learn.

A label such as honors or standard can be fatal to a student’s self identity. One label piles on the pressure that can scar students with a fear of failure and unrealistic expectations to be perfect. The other label tricks students into believing that they are incapable of learning at a high level, breeding self-doubt that often turns into low motivation and low effort. Can you blame them?

Falling prey to labels affects us, too. Of course, we know not ALL honors kids are perfect, well-behaved children who understand concepts right away. And we know not ALL standards kids are behavior problems and incapable of learning high level curriculum.

In the past, those labels set me up to miscalculate my students. My assumption about students was for them to be stereotypical. In other words, the labels warped my expectations and that negatively affected my teaching. I set extremely low expectations for my standards students solely because they were labeled standard, and vice versa, I set the bar at unprecedented heights for my honors students, expecting perfection.

Short of overhauling the tracking system, my hope is that we all treat our students as if they are mathematicians, or scientists, or historians. You will start to see a change in your kids; they will not only be engaged, but they will be excited to learn.

Now I treat every day as an opportunity to push each of my students to achieve his or her full potential — not the one prescribed by a label.