Editor’s Note: This article was originally published by The 74 on Oct. 31. You can sign up for their zero2eight Substack community here.

The National Head Start Association is tracking confirmed Head Start closures by state on its website. As of Nov. 4, three grantees in North Carolina have closed programs: East Coast Migrant Head Start Project, which provides services across 10 states, Salisbury-Rowan Community Action Agency Incorporated, and Southeastern Community Action Partnership, Inc.

Most Mondays, Shannon Price arrives at school and gets her 17 Head Start preschoolers ready for their morning activities, typically lessons on how to grip a pencil and write their first names. It is work she loves and feels deeply committed to, not only as a teacher, but also as a former Head Start kid and parent herself.

But this Monday, she didn’t have a classroom to go to.

That’s because the ongoing government shutdown forced her Highland County, Ohio, program to shutter, impacting 177 kids and 45 staffers. Across the state, at least three providers were set to close their doors, cutting off services to at least 1,000 young children and employment to 286 Head Start workers.

And Ohio is not alone. In all, 134 programs across 41 states and Puerto Rico serving 58,627 children were at risk of closing on Monday, Nov. 3, as federal funds expired over the weekend. Since the beginning of October, an additional six Head Start programs serving 6,525 children in Florida, South Carolina, and Alabama have been operating without federal funding, drawing on emergency local resources to keep their doors open.

In total, these approximately 65,000 kids account for close to 10% of all of those served by the early learning and child care program for lower-income families.

![]() Sign up for Early Bird, our newsletter on all things early childhood.

Sign up for Early Bird, our newsletter on all things early childhood.

News of their Head Start program’s closure has hit Price’s community in the Appalachia foothills particularly hard.

“I had a parent come up and grab me and hug me and she cried and I cried,” she said. “You know, a lot of parents really rely on our program. It’s pretty much invaluable in our county.”

Sarah Allen’s family is among those feeling the pain. Her 3-year-old daughter Hallie attends Head Start while Allen, a former Head Start teacher herself, works on obtaining her state teaching license and substitute teaches at the local school to make extra money. Her husband is a firefighter.

Starting this week, they’ll both have to work fewer hours to stay home with Hallie, creating financial hardship for the family.

“I can’t work if I don’t have a babysitter and prices keep going up for everything — and food costs are crazy,” said Allen, who is also worried about the interruption to her daughter’s education.

Many Head Start families could face a double blow, losing access to the program and food assistance at the same time, with funds for the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) also set to run out. An infusion of contingency funding from the White House in October for the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children, also known as WIC, is expected to be depleted in a few more weeks.

On Nov. 3, the Trump administration announced plans to use $4.65 billion in emergency funds to disperse 50% SNAP payments to the 41.7 million Americans who receive the benefits. However, distributing partial November benefits is expected to take time as states calculate benefits for each household.

About 50 miles south of Highland, right along the Ohio river, sits Scioto County, another Appalachian stretch, parts of it so rural that some communities don’t have stop lights. On Monday morning, Head Start classrooms across 10 centers in the region — serving 400 early learners and infants — were set to shut down and all 100 staff members, 60% of whom are former Head Start parents, to be furloughed.

Communities in Scioto County were decimated by the opioid crisis, leaving many kids to be raised by grandparents or other family members, who are heavily reliant on Head Start programming, said Sarah Sloan, early childhood director of the county’s Community Action Organization. Other parents are in recovery themselves, she added, and lean on Head Start to provide a safe and stable place for their kids.

Their programming is where families already under stress come to get help, she said.

Despite this, the reception to the grim news that classrooms would close — from both families and staff — “has just been so generous,” Sloan said last Wednesday, her voice cracking.

“I have not heard one negative word from our parents. They have said things like, ‘We are in this together. We understand. We hate it for your staff. We’re worried.’”

Some states find last-minute funding, others don’t

The 74 spoke with over a dozen Head Start Association presidents, providers, teachers, and parents in Florida, Georgia, North Carolina, Missouri, Ohio, and Washington, the six states with the largest number of seats at risk.

Some states, such as Ohio and Washington, are bracing for imminent closures, but others, such as Missouri and most of Georgia, have been able to access other sources of funding, giving them a runway of a week or two. This means that where a young child lives will determine whether or not they have a staffed classroom in a few days and if their families can access the range of other resources Head Start offers, from health care services to parenting courses.

While each state faces it own challenges, a few universal themes emerged: an assertion that even if local Head Start organizations are able to scrape together enough funding to keep their doors open, it will only be temporary, extending access for a few days or weeks; fear that the borrowed funds to stay operational may not be reimbursed once the federal government reopens; and concern that low-income families will lose access to food assistance at the same time.

Head Start, which turned 60 this year, provides children at least two meals a day. All of this is setting off alarm bells about the unprecedented nature of the government crisis and the devastating effect it will likely have on the country’s most vulnerable families.

Related reads

They will begin feeling the blowback from D.C., as some parents are forced to choose between caring for their kids and showing up for work.

Funding for Head Start is complex. Some 80% comes from federal grants that are released to local providers on a staggered schedule throughout the year. Grant recipients with funding deadlines on the first of October and November are now scrambling, as the second-longest federal shutdown in history continues.

While there appeared to be some movement last week, Senate Republicans and Democrats have repeatedly failed to come to an agreement on a funding bill. Democrats are demanding an extension of tax credits that have allowed millions of people to access health care since the pandemic, while Republicans say they won’t negotiate until Congress passes a bill to reopen the government.

President Donald Trump has largely targeted blue cities and states with cuts so far, though interruptions to Head Start funding would impact thousands of families across the political spectrum, with some of the severest programming losses falling on red states.

This has all compounded existing financial strain on local programs, many of which have struggled to hire and retain teachers, according to the National Head Start Association. It also follows multiple funding threats and deep staffing cuts by the Trump administration that have plunged Head Start programs across the country into chaos and uncertainty this year.

‘These are actual people’

No state has more seats at risk than Florida, with 9,711. While the majority of centers across the state will be able to remain open through the first two weeks of November, at least one program in West Palm Beach serving children of migrant families and seasonal workers was forced to shutter last weekend, according to Wanda Minick, executive director of the Florida Head Start Association. The closure will impact 386 children and 283 staff across six centers, she said.

Minick wants Congress and the president to understand, “These are not just data points. These are actual people.”

In neighboring Georgia, policymakers were preparing to potentially close centers serving 6,499 children and infants, until a last-minute, bridge loan from The Community Foundation of Greater Atlanta’s Impact Investing Fund came through last Tuesday. The $8 million means that three major providers, serving 5,800 kids, will remain open for at least 45 days, though that leaves hundreds of others throughout the state still in a lurch.

Juanita Yancey, executive officer of the Georgia Head Start Association, expressed her gratitude for the money while emphasizing that it’s only a stopgap measure.

Related reads

“Time is running out,” she said. “Programs are doing everything possible to keep their doors open, but they cannot run a program on reserves or goodwill. Every day of inaction is another day of uncertainty for families who count on Head Start services.”

“This shutdown is pushing programs to the breaking point when children and families can least afford it,” she added.

The bulk of Head Start seats in Missouri also appear to be safe — at least for now, according to Kasey Lawson, director of the Mid-America Regional Council, which serves 2,350 kids across 17 providers. Though that still leaves about 1,500 seats unaccounted for.

For Lawson’s 17 providers, the choice to remain open is both temporary and a risk, she said, since the centers don’t have that money “just sitting in the bank,” and they fear they won’t receive backpay once the federal government does reopen.

Lawson said they’ve asked legislators, members of Congress and the federal Office of Head Start, which is under the Department of Health and Human Services, to guarantee reimbursement as they have in the past, yet “nobody’s willing to do that. And so it is the reality of where we sit right now, that it is a true risk that all of our agencies are taking.”

And even though most Head Start families in Missouri had a place to send their kids Monday morning, many may still face a significant burden as at least 1,100 rely on expiring SNAP benefits.

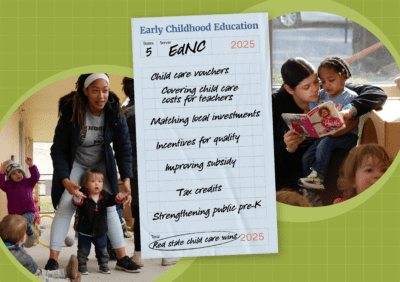

In North Carolina, where 4,697 seats are at risk, at least one center was forced to close on Friday, said Terry David, president of the state’s Head Start Association. Classrooms that are based in the local school district should be able to remain open through the end of the calendar year, he said, but that only accounts for about 140 kids.

Across the country, in Washington state, at least one program in the city of Vancouver, which serves at least 175 kids, will close this weekend. Another in the same region, The Margaret Selway Early Learning Center, will remain open through Nov. 7, but each day beyond that is uncertain, according to Nancy Trevena, chief strategy officer at the Educational Opportunities for Children and Families.

Kimberly Gusey’s foster son, Ranger, is a student at Margaret Selway and is especially dependent on Head Start services. The program was able to secure a one-to-one certified nursing assistant for Ranger, who has cerebral palsy, is nonverbal and is fed through a G-tube.

“It’s amazing,” Gusey said, her voice breaking. “It brings me to tears how much they’ve done for us.”

If the program closes this week, Gusey’s husband will have to quit his job as a mechanic to care for Ranger.

“We’re talking a large amount of money not coming into our home, but we’re willing to do that because we love these children,” she said. “But in so many ways it affects us. Not (just) the pocketbook. The routines for the kids. The routines for us. Everything is affected by this.”

Recommended reading