|

|

Back in person after the pandemic with more students from nine different counties together in a new school building, and with racial tension in the school and community at a high point after the killing of Andrew Brown, this school allowed students to lead the way, building a school culture around respect and inclusivity. This series includes five student perspectives and two perspectives from the guidance counselors in their own words.

These pieces include references to racist imagery and language.

By the time a Black student found himself, fists clenched in the throes of anger, face-to-face with a fellow student who had just called him the N-word, racial tensions had already gotten out of hand at the Northeast Academy for Aerospace and Advanced Technologies (NEAAAT) in Elizabeth City.

In truth, as it was in the school, so it also was in the community.

“This was a major blow up, but we’ve been having this problem,” said senior Janiya Wallace.

School administrators talk about the “NEAAAT-way,” which they hoped created a sense of family for the students. But there had been issues in the past.

Like when a student was spit at, called the N-word, and told to go back where they came from — all the more surprising because it happened during a visit to Elizabeth City State University, a historically Black university. The negativity transcended racial differences – “it was all of the above,” three students said. But in the months following the killing of Andrew Brown, tensions reached a high mark.

“This year is when I started to hear from other students that there was more tension and discrimination toward some people,” said senior Luke Edwards, a white student. “Before this year, I didn’t think it was as bad. But this year it seemed to kick up a little more.”

Earlier this year, students found a noose hung over each of the three urinals in the boy’s bathroom.

And then came that incident in the multipurpose room, the one which left a Black student seething and the white student who used the derogatory word quickly surrounded by several other Black students. Parents were getting calls, and Janiya said she saw some running into the building afraid something terrible would happen.

An altercation was breaking out and administrators rushed to break it up. This was the turning point. It was the nadir for the school community, a culmination of so many factors.

Schools across the state reported a rise in disciplinary issues this past year, the first for all students coming back in person after attending school remote from home.

“These problems likely festered during the pandemic as people interacted less and less, so I guess it makes sense that there might be more conflict as people begin to interact more.” Read sophomore Payson Meader’s Perspective.

For NEAAAT, it was also the first full year in a new building. During the pandemic the school grew to include two more grades (it added fifth grade in 2020-21 and sixth grade in 2019-20).

All of a sudden, there were more kids in a new place. With hybrid offered in 2020-21, all of them hadn’t been together since before the pandemic.

“All that going on, and then you had people who were sensitive to the [Andrew Brown] situation, and people who were not sensitive to the situation,” said Janiya, who lives in the same community Brown did and heard the gunshots that killed him while she was walking to work.

“The killing of Andrew Brown was a tornado that hit Elizabeth City. School days were a way to relieve stress and get away from my home environment, but when you are here your back is against the wall if you’re Black.” Read senior Janiya Wallace’s Perspective.

The geographics play a role, too. The school pulls from nine different counties. And these counties are demographically, economically, and culturally different. Camden and Currituck, for example, are more white and affluent than Pasquotank, where Elizabeth City sits.

Pasquotank, itself, offers a study in cultural division. The county is mostly white, while the county seat — Elizabeth City — is mostly Black.

“What we’ve experienced at NEAAAT is less a school issue,” NEAAAT CEO Andrew Harris wrote in an email, “and more the tattered areas in the fabric of our community surfacing through our students as they grapple with their own lived experiences across our school’s wide geographic footprint and subcultures.”

“Growing up in this city, there has always been division, but that division was never really discussed. Leaving things unspoken was like putting a Band-Aid on a wounded area — things become infected.” Read counselor Latonya Frost’s Perspective.

With so much change and fracture, students felt it was time to set a tone for the culture of the school. Far from out of control, the students wanted more control. They asked if they could lead an effort to encourage unity on campus.

It started with the Black student who had been insulted in the multipurpose room. He was angry, but more than that he was determined that it not happen again.

“This has happened more times than once,” he said. “I don’t want someone else to go through this.”

Samantha Doran and Latonya Frost, counselors at the school, were among the first to hear the idea and support it.

“If I didn’t acknowledge what I was hearing from the students, I would not be working for them. I would not be putting the students first.” Read counselor Samantha Doran’s Perspective.

They sent an email to several student leaders. Would they take ownership of the effort?

“We wanted to make sure from the beginning that it was student-led,” Doran said. “We’ll provide the space for you guys to come together and time to come together and work on this, and we’ll help brainstorm with you — but it really needs to come from the students.”

Initially, it was a handful of mostly Black students. Those students, though, started to recruit others.

“It was a panel full of ‘us,'” Janiya said. “I love us, but you need some swirl in there.”

Soon, they had a group, about 15 strong, and they resolved to meet with every one of their classmates. They put together a presentation – a pitch for respect and inclusiveness.

“I think this all signified the start of the transition of our student body from students without a voice to students that feel comfortable identifying and tackling these issues that affect them on a daily basis.” Read senior Luke Edwards’s Perspective.

Every morning, students attend “advisory” — it’s kind of like homeroom, except it includes a full curriculum centered on career and college readiness and social emotional learning. Advisors stay with the same group of students throughout their four years of high school to foster interpersonal relationships between students and adults in the building.

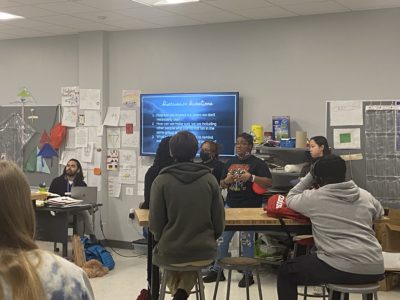

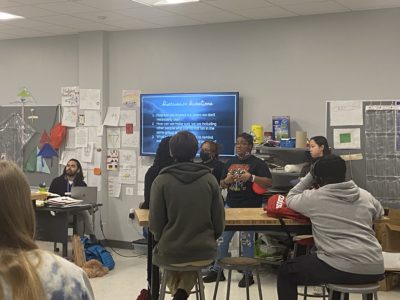

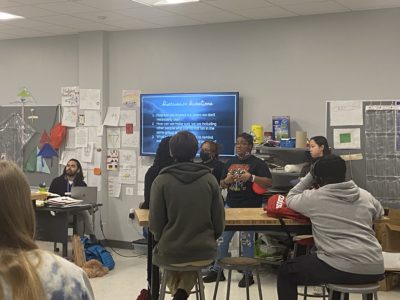

The student leaders broke into groups and presented their vision at every high school advisory over the course of three days just before spring break. The presentation included a PowerPoint, as well as an interactive component to get students talking.

The conversations were sometimes heavy. Some groups asked students to write anonymously about whether they felt safe at NEAAAT. The responses were mixed.

“Our school has people coming from everywhere experiencing everything. And experiencing things differently.” Read senior Janarria Wallace’s Perspective.

“What does it mean to be respected?” Janiya said. “What does it mean to be included? How do we act on it? We made a presentation and now we’re here.”

Some students were on board immediately. Others seemed like they were ignoring the presentation, but afterward advisory coaches said classrooms filled with discussion. The team – dubbed the Respect and Inclusiveness Group – gave their email addresses to peers and emails trickled in.

Some emailers were optimistic. Others were skeptical that the culture would shift. In the months since, however, racially motivated incidents have dwindled. Students are noticing more acts of kindness.

What matters is what you’re going to do about the situation to better yourself. Maybe once everyone gets that, this world would be at peace. Read junior Jamiya Rouse’s Perspective.

And the Respect and Inclusiveness Group is still doing work. They’ll randomly challenge their peers to acts of kindness, like finding someone and saying something nice. The school holds “mix and match” lunches, where students swap seats after settling in the cafeteria so they can get to know someone new.

“We had one kid tell us, ‘I finally feel like I have someone to talk to,'” senior Janariya Wallace said. “That was the goal. That almost brought a tear to my eye because that was it. That’s what I want all the kids to feel like.”

It’s funny, Doran thinks. The solution was baked into a core value of the school all along: student-driven design. She was once among those who wondered if the kids were out of control. Now, she realizes, the solution was putting them in charge.

“I feel like I’ve heard a lot more conversations among students,” Doran said. “Even in the hallway in the morning, we’re normally right out front where the students get dropped off by parents, and I’ll hear conversations about ‘remember the respect presentation we saw.’ I think it’s stuck with them. They heard something.”

Recommended reading