Jim Parker left his previous position with the NC Department of Information Technology to join the North Carolina Community College System in 2016. As chief information officer and senior vice president for technology solutions, he soon realized that the system was spending a lot of resources to maintain the capabilities it already had, but was not doing as much in the way of technological innovation.

“We needed to start carving out resources and time to help focus in on what technology we needed to innovate in order for us to have a successful future,” said Parker. “And artificial intelligence is just one of them.”

Enter Tanjo, a company founded in Research Triangle Park in 2014 that “brings machine learning and automation to transform businesses, reshape industries, and enrich people’s lives.” According to its website, Tanjo “improves and automates the ‘discoverability’ of organizational knowledge by fostering a balanced partnership between people and machines.”

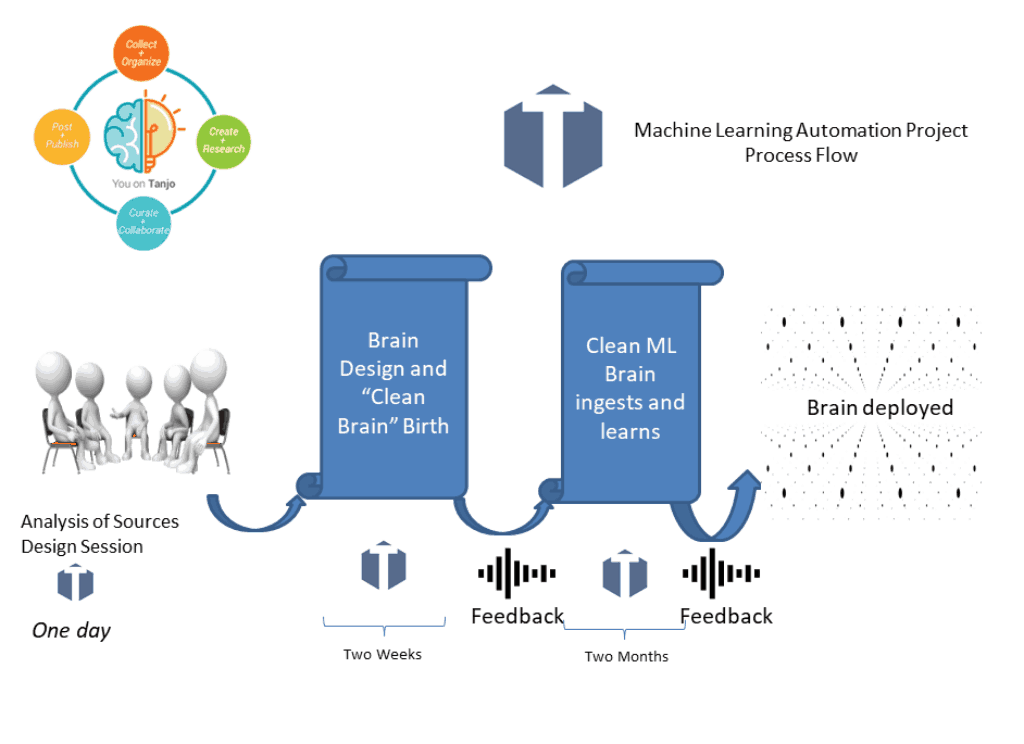

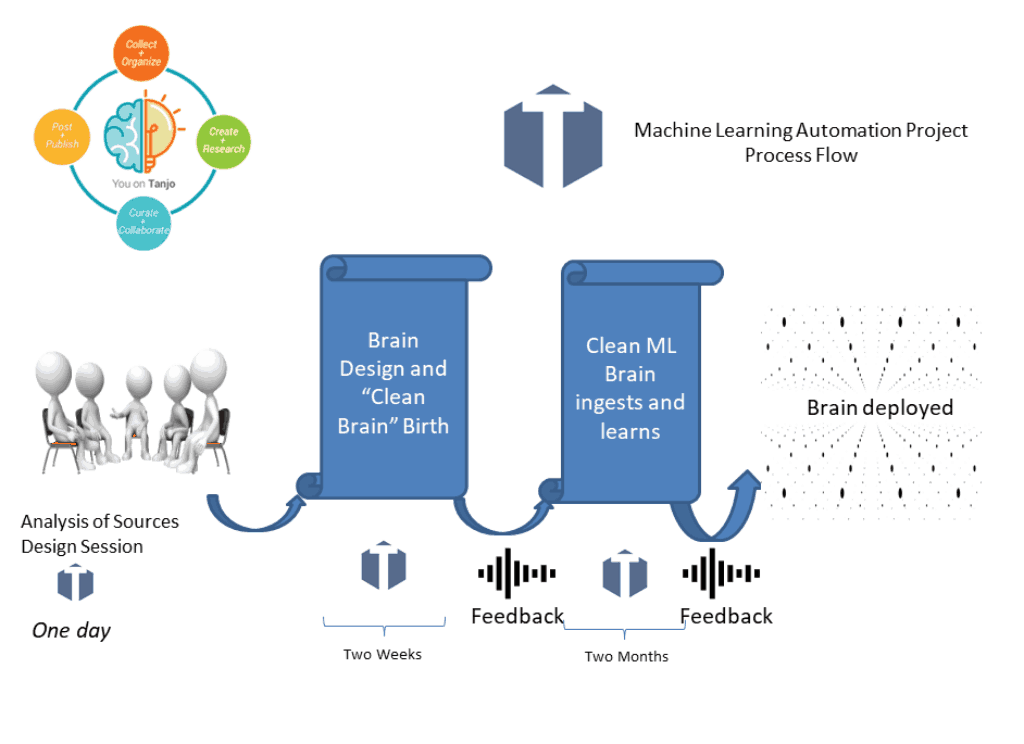

The first step in the partnership between Tanjo and the community college system, according to Tanjo CEO Richard Boyd, was for the company to conduct a study of what areas could be addressed with machine learning within the system.

“Usually the low-hanging fruit is that first step of let’s look at the organizational knowledge you have — the information — where is it and in how many data cubbyholes is it stored? How can you organize it all and map it and make it available to people as they need it in a friendly, efficient way?” said Boyd.

From that process, Tanjo and the community college system realized there was an opportunity to implement Tanjo’s Enterprise Brain to learn and track organizational knowledge across the 58 community colleges and the system office.

For Parker, the brain technology presented an opportunity to harness the synergy of seamless access to data and information from a system that serves all 100 North Carolina counties.

“We have 59 — counting the system office — buckets of intellectual property, data, information, and history spread throughout the entire state. One of the challenges we face is how do we capture that information? How do we bring that information together so that we can leverage it to enhance each other? All of us are smarter than any one of us,” said Parker.

Without a way to track, organize, and understand all of the data and information within the community college system, it is difficult to know how information is used and what it is used for. The consequence: information is lost every time a community college staff or faculty member retires or leaves the system. According to Parker, that loss of intellectual knowledge and experience can be painful for colleges.

Although humans are able to curate this information, it can be a time-intensive, expensive process. The information exists in a variety of formats, and not all of the information needs to be retained — part of curation is knowing when to get rid of different objects.

Machine learning instruments, like the brain, can catalog and curate those same objects more efficiently. Parker compared the process to cleaning out the garage or curating artifacts at the Smithsonian Museum.

“It’s a chore to clean out the garage. If you can find a robot that can fulfill your intentions and ask you questions like: Do you want to throw this out? Do you like these things? Are you sure? Hey, you threw this out, so do you want to throw this out as well? That’s where the purpose of the technology comes in. It can help us identify what we have, how it’s formatted, and what the content is,” Parker said.

Beyond just cataloging and preserving learning objects from across the system, the brain will make sure those objects are made easily available to faculty and staff who could benefit from them. This breaks down the silos between information, ensuring that anything known by one college is known by the whole system. More on that later.

Parker added that this technology could also be leveraged to better understand the more than 750,000 students and more than 30,000 faculty and staff in the community college system.

“Ultimately, we also want to use this to better understand our student population and the demographics there. We also want to better understand our financials and our faculty and staff,” said Parker. “We’re not a small institution. Even though we are community-driven and the local entity has the responsibility to deliver services at the community level, we also need to understand it from a system perspective.”

In terms of a timeline, Boyd said the brain is still in its learning stage right now, but will soon be rolled out to specific colleges who volunteer to test it first.

First, the brain reads and processes all of the learning objects in the community college system. The term learning objects includes everything from PowerPoint files, to videos, to syllabi and study guides, to emails. A lot of these materials are not standardized in any particular format, so the brain works to make them uniform and catalog them accordingly.

For community college faculty and staff, the technology will then operate as somewhat of a personal assistant. According to Parker, that assistant would be tailored to the faculty or staff member using the system based on their role and needs. For example, the brain would know the courses they teach, how long they’ve been teaching, what course materials they use, and information on the students they serve. Using that information, the brain can detect what information the user is searching for and offer resources quickly.

“What I envision this brain to do is to say:

‘Hey, just so you know, here are five other items that might be useful for your coursework,’ and make it available to them,” said Parker.

“Or, it could say: ‘I noticed based on the grades you have for your students that they struggle in this part of your program of study.’

The brain could then find some material that could help you as the faculty member to teach that area more effectively.”

Although faculty and staff previously had access to these materials, they may not have known how to access them, and it was a time-intensive process to find the right resources. The goal, Parker hopes, is that this automated way of accessing resources will allow faculty and staff to be more productive and effective in their roles.

Another use of the brain is for the intergenerational transfer of knowledge. As a staff or faculty member works within the system over the course of their career, their behaviors and information needs are captured within the brain. If an instructor retires and their responsibilities are passed to a new instructor, the brain can aid in the continuity during this turnover and work to get another instructor up to speed.

Boyd refers to this as solving “the Silver Tsunami” problem.

“The gray-haired people know how to land a spaceship on mars and control robots. When they retire, they take a lot of knowledge with them,” said Boyd. “How do you replace them with people quickly and where you might not have the apprenticeship model available to you?”

Turnover is especially prominent among the presidents of the 58 community colleges. According to materials from a November 2018 State Board of Community Colleges meeting, 29 new presidents joined the system between 2015 and 2019, with six additional colleges searching for new presidents. The brain, Boyd said, will have the capability to provide a shadow map to new employees of the person who held that same position before them.

“When they got set up for fall term, what resources did they go to? What people did they talk to? What documents did they access? What curriculum objects did they use?” said Boyd. “Can we make people more effective by giving them that help when they move into that job?”

For the system office, the brain will offer a way to better understand how resources are being used and how to optimize funds spent on those resources. According to Parker, the system offers several thousand learning objects to its 58 colleges — some which are free, and others that the system pays for.

“If I spend $250,000 on supporting subscriptions for learning objects, I want to know whether or not that is money well spent. By using the brain, you could track how many people are using those materials,” said Parker.

The ultimate goal of this technology all comes back to the students.

For Boyd, personalized learning maps for every student that helps them achieve success attuned to their goals is the holy grail of the project. For example, if a student knows they want a job as a nurse or an engineer, the system pairs that desire with information about unique qualities of the student, such as their learning style.

“The algorithm is called ‘people like you’ — people with your attributes and preferences. What did they have access to that made them successful? Not just the courses you should take. It’s the informal elements — 65 percent of all education is informal. It’s about being able to access things outside the classroom that make you more successful,” said Boyd.

Those elements Boyd is referencing are a lot of things that students seek advice about from school counselors. The brain has the ability to provide personalized guidance to students on everything from curriculum advice, to financial aid resources, to connections with other students and faculty members doing similar work.

Parker echoed Boyd’s sentiments, saying that the community college system hopes to one day leverage this technology to better map student pathways and improve student outcomes. He referenced the ability to conduct a statewide study that would identify the behavioral factors that drive student success in different regions of the state, and the ability to model various curriculum pathways for students to explore.

“One of the challenges I think students run in to — one of the things I see and hear about — is the pathway. What should my pathway be? Where does my pathway need to go next to be successful and efficient?” said Parker. “Every step costs money to a student. I think this should help a student not only determine a path but also set up potential scenarios — what if I did this? What would my path look like then?”