A bill to open up the educator preparation system in North Carolina to organizations other than universities could bring big changes to the way the state trains teachers.

The vast majority of teachers in North Carolina classrooms are trained at universities. And while Senate Bill 599 has some hurdles left to clear, if it becomes law, it would allow private, for-profit programs to assume some of the teacher training responsibility in the state.

A Texan model?

Sen. Chad Barefoot, R-Wake, sole sponsor of SB 599, said the bill was based in part on the approach in Texas. The educator system in the Lone Star state is much more open to alternative educator preparation routes. The idea of alternative certification — outside the traditional degree system — has existed in the state since 1984, according to Lauren Callahan, an information specialist with the Texas Education Agency.

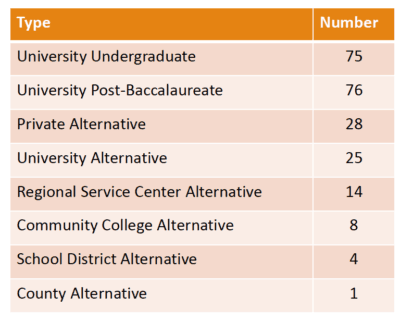

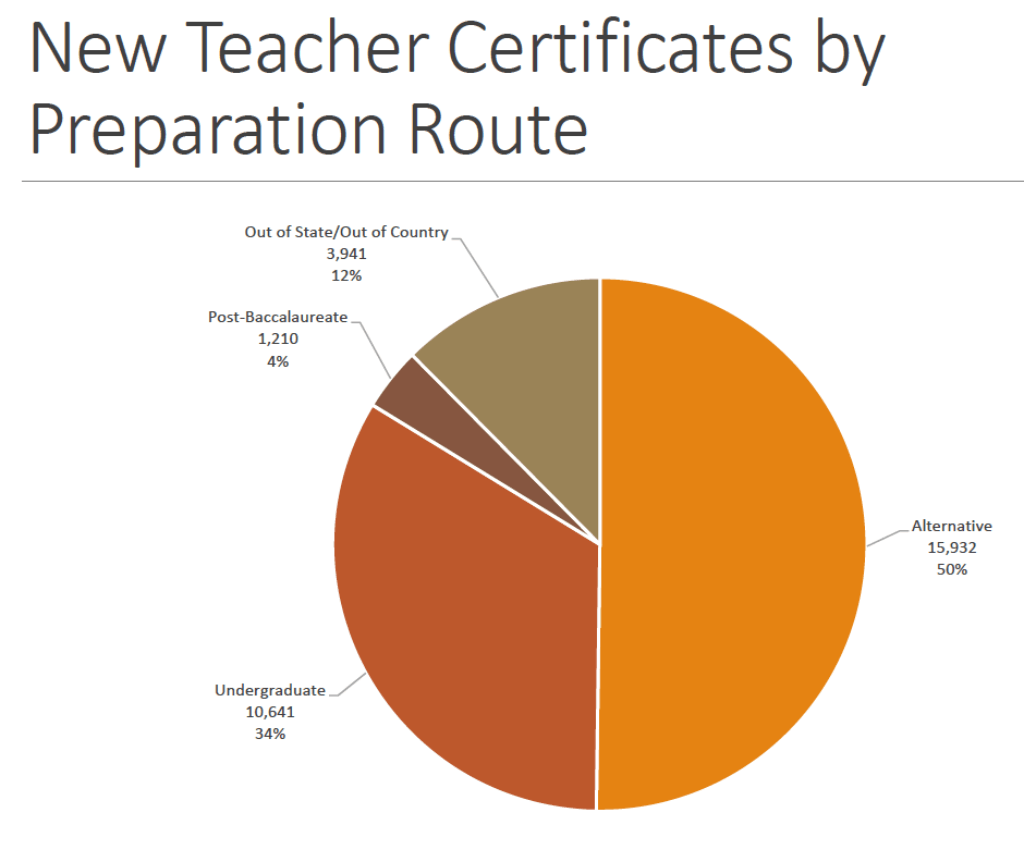

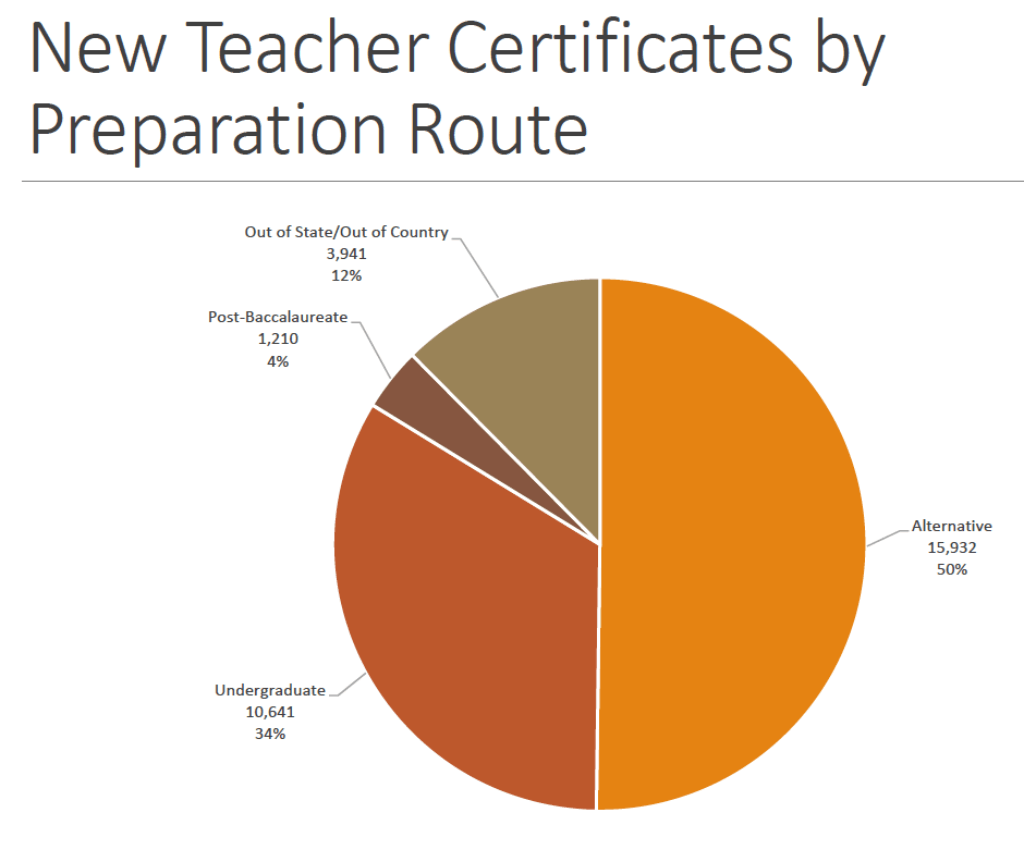

According to data from the Texas Education Agency, traditional university programs make up nearly two-thirds of the total preparation programs but only 38 percent of the total new teacher certifications.

Teacher preparation programs in Texas, 2016

While only about a third of the total number of organizations are non-university, these alternative programs comprise 50 percent of new teacher certificates in the state.

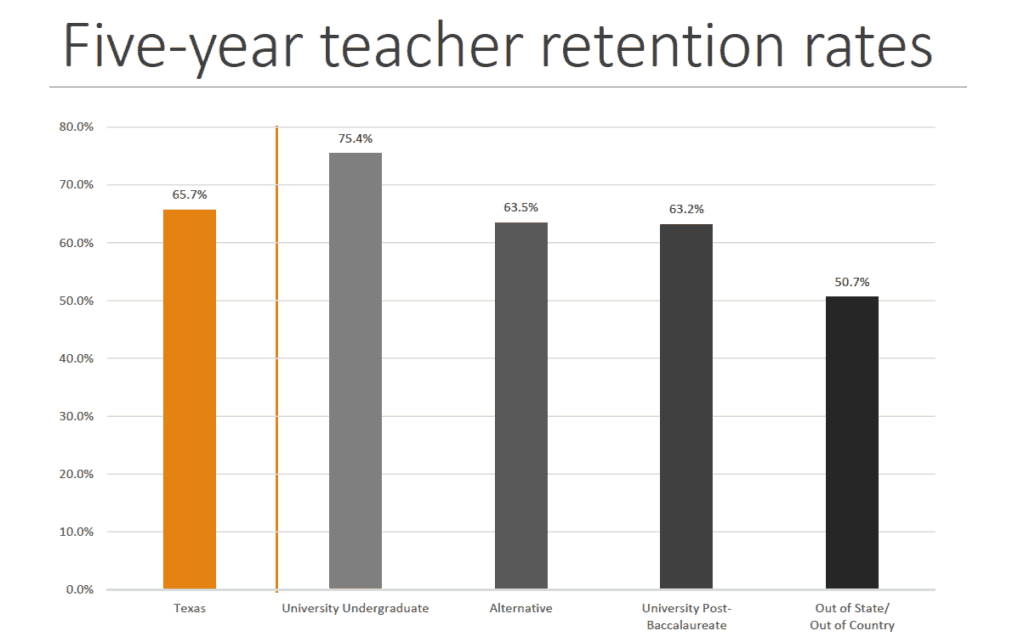

In terms of retention rates, undergraduate university programs outpace alternative options — 75.4 to 63.5 percent.

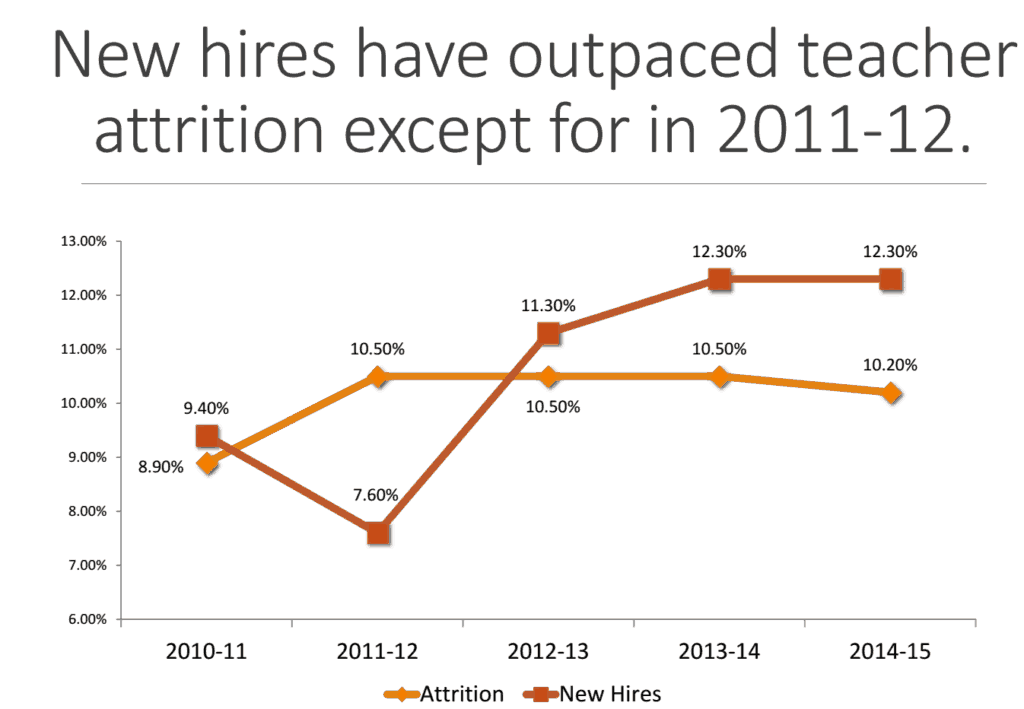

In his rationale for the North Carolina legislation, Sen. Barefoot cited a concern for the supply of teachers in North Carolina not meeting demand. Indeed, many districts complain of difficulty in hiring the teachers they need. Between 2010 and 2015 in North Carolina, enrollment in teacher preparation programs in the UNC System has declined by 30 percent.

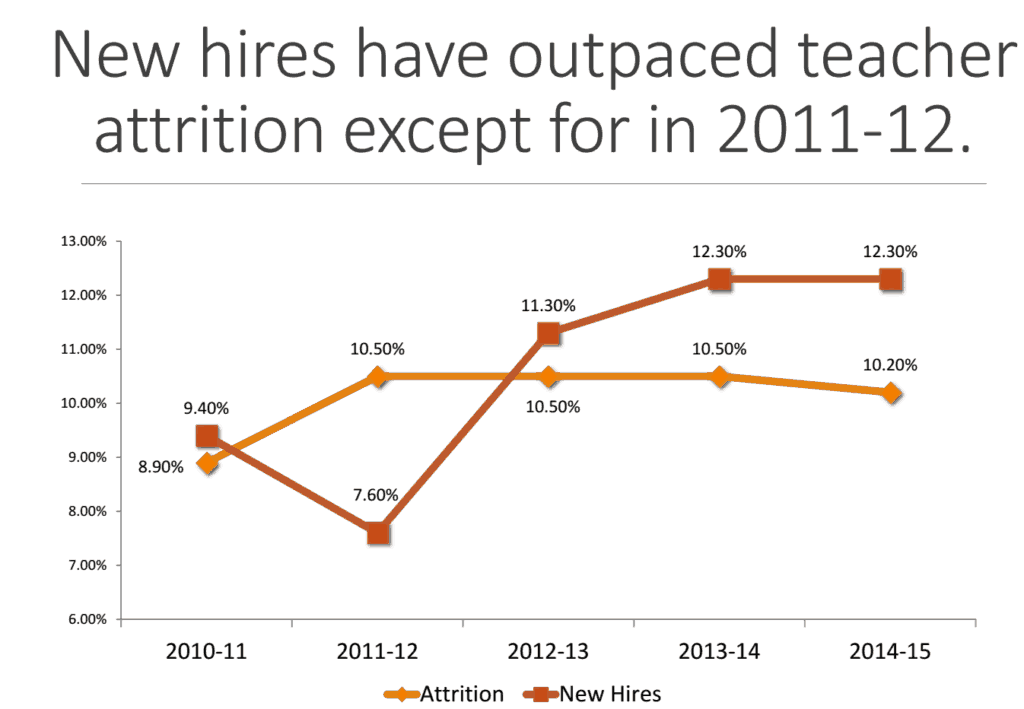

In Texas, the open system of educator preparation seems to be keeping supply above demand, at least as of the 2014-15 school year.

What about North Carolina?

While Texas and North Carolina face similar challenges, there are distinct differences between the education systems in the two states.

Texas was home to 347,272 teachers in the 2015-16 school year, while North Carolina employed 94,304 traditional public school teachers and 5,708 charter teachers in 2017.

The Education Policy Initiative at Carolina —housed within the department of Public Policy at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill — periodically analyzes different ways teachers come into North Carolina schools. Part of their research examines teachers who went through alternative teacher preparation.

Alisa Chapman, a visiting fellow in Public Policy and the Global Research Institute at UNC-Chapel Hill, said the UNC system’s education programs are the single largest supplier of teachers in North Carolina. The most recent data, from the 2013-14 school year, shows that about 37.5 percent of the teaching workforce comes through this route. About 28.7 percent of teachers come from out-of-state programs where they received a degree and license. Fifteen percent of teachers come from alternative entry programs.

The category of “alternative teacher preparation” is a catch-all in the state, according to Chapman. It may include teachers who went through the state’s Regional Alternative Licensing Centers operated by the state Department of Public Instruction. It could also include those who completed alternative licensure programs at public and private universities.

And it can include teachers from out of state who may have attended the types of programs that could come into the state for the first time under Barefoot’s bill.

Just as in Texas, alternative preparation programs do not have teacher retention rates as high as those who were educated in the university system in North Carolina, Chapman said.

About 85.8 percent of UNC-system-trained teachers return for a third year, and 73 percent of teachers return for a fifth year.

Of teachers trained in alternative programs, a little more than 70 percent return for a third year. The percentage drops to just under 50 percent for teachers returning a fifth year.

Alternative programs in North Carolina have demographics that differ from those of university programs. Forty percent of teachers who used an alternative program were minorities, compared to 17 percent in the UNC-system programs.

“That’s actually a really critical point,” Chapman said. “We need to do a better job in addressing diversity in our programs.”

Teachers who went through alternative entry programs favor high school placements. About 49 percent teach at the high school level, with 29 percent teaching in middle schools and nearly 20 percent in elementary schools.

Roughly 10 percent of teachers who come from the UNC system teach exceptional children while about 16.7 percent of teachers who came from alternative programs teach exceptional children.

“That’s a figure to note,” Chapman said. “That’s likely filling such a critical need. We have very high turnover of exceptional children teachers in our state.”

When it comes to the impact that teachers trained in alternative programs have on students, Chapman’s data shows university-educated teachers perform better.

“Our data show that the category of alternative, these teachers do not fare as well in our value-add analysis,” she said. “They have lesser impacts on student achievement as it relates to test scores.”

In elementary math, Chapman said these teachers have “significant negative impacts,” on student achievement when compared to teachers trained in a more traditional route. The data is similar at the middle school level, with alternatively trained teachers having a lower impact than their traditionally-trained peers, particularly in math.

In high school, alternatively-trained teachers perform a little better in English/language arts than peers trained at traditional public or private programs, but they do not do as well in math and science.

Alternative entry teachers are also less effective when it comes to low-income students. These teachers perform at a lower-level than their university-trained peers in instruction of students who qualify for free-and- reduced-price lunch.

While there are pros and cons to alternative programs as a whole, Chapman says the key is choosing the right programs.

“Alternative entry is not going away,” she said. “It’s a matter of finding those alternative routes of licensure that are of the highest quality.”

How will alternative programs operate?

Ensuring that the new educator programs are sufficient is a task for the Professional Educator Preparation and Standards Commission created under Barefoot’s bill.

The commission will oversee all state educator preparation programs, including those at universities. It will be made up of teachers and administrators that will make recommendations on educator preparation programs to the State Board of Education. The commission will also develop rules related to the programs.

The State Board will have the final say on the standards for programs and determinations about whether programs meet the standards. The commission will also submit a yearly report to the General Assembly summarizing any recommendations or findings they have about improving the teaching profession.

The bill also sets forth detailed standards that educator preparation programs will need to meet, including high-quality clinical practice, a demonstrated impact of its graduates on student learning, and a “quality assurance system,” which uses multiple data points to demonstrate the efficacy of its program.

In addition, the bill includes accountability measures that the educator preparation programs will be held to, including performance measures related to proficiency and growth of students, results from the educator satisfaction survey, and quality of students entering the program.

The programs will have to submit annual performance reports to the State Board as well. Go to the bottom of page 9 of the bill for the whole section on accountability.

SB 599: Yay or nay?

As with any legislation proposing big changes, SB 599 has its supporters and its skeptics.

Mark Jewell, president of the North Carolina Association of Educators, does not support the measure. “This is very concerning,” he said.

He is worried about the quality of some of the for-profit, online organizations that might come into the state under the bill.

“To me that sounds like a different version of what our students are going through with the virtual online programs, which aren’t nearly as robust,” he said.

Jewell refers to two controversial online virtual charter schools operating in North Carolina. They are different from the virtual public school operated by the state.

He also said the NCAE was not contacted for input on the bill, and he is concerned that the governor does not appoint any members of the commission that will oversee the program. All commission members will be appointed by the General Assembly.

But his bigger concern is that the bill does not address the underlying problems facing the state.

“We have a major teacher shortage crisis in North Carolina, and we have for a number of years,” he said.

He blames the shortage on the General Assembly eliminating longevity and master’s pay for teachers, dismantling the previous Teaching Fellows Program (revamped and reintroduced to the state in the new state budget plan), and not investing in a high-quality public education system.

Jewell said the state was once considered a leader in education, but that is no longer the case, and it is hurting interest in teaching as a career.

Charles Coble shares some of Jewell’s concerns. Coble was dean of the College of Education at East Carolina University for 13 years from 1983-1996 and later served as vice president of the university and a member of the Education Commission of the States. He now lives in Chapel Hill and operates Teacher Preparation Analytics.

“I think they’re addressing the wrong problem,” he said. “It’s not that we’re suffering for different ways of coming into teaching. We have a lot of different opportunities for people to enter teaching in North Carolina.”

He says that what teachers need is better support from the state. The reestablishment of the Teaching Fellows Program and other programs addressed this General Assembly session are steps in that direction, but he said SB 599 is the wrong strategy to bolster the supply of teachers.

Michael Maher, assistant dean for Professional Education and Accreditation at North Carolina State University’s College of Education, is not concerned about Barefoot’s legislation. He is one of the stakeholders who talked with Barefoot and gave input on the legislation.

“I think for a long time, we have in essence taken issue with groups being able to operate inside of North Carolina without having to go through the same processes that we have to,” he said.

He references organizations like the University of Phoenix and Teach for America, two very different programs that have both been allowed to prepare teachers in the state without going through the same procedures as traditional educator preparation programs.

Maher said the Commission created by Barefoot’s bill will oversee all educator preparation programs, traditional and alternative, and so there will be no loopholes for anybody; all programs will be held to similar standards.

Maher doubts there will be much pushback on the new law from other university educator preparation programs. He pointed out that the program approval process and some of the requirements in Barefoot’s bill are, in many cases, re-codification of rules that already existed.

“It’s not like all of a sudden teacher prep programs are going to look at this bill and freak out because there’s a lot of things they’re asking us to do that we weren’t doing before,” he said.

Barefoot’s legislation initially passed the Senate and then the House. But the House amended the bill along the way, and the Senate did not agree with the changes. Last night, senators voted not to concur with the amended bill. Now a conference committee with members from both chambers will try to work out lawmakers’ differences.