Several weeks ago, I faced a daunting task for any hopeful teacher candidate: I took the Praxis exam. The first of two tests I must pass until I am licensed in Special Education (Adapted Curriculum K-12), the one I recently took focused on my knowledge of educating students with severe and profound disabilities. It’s my specialty area, my passion, and something I’ve spent the last four years of my life studying. And I couldn’t have been more terrified.

I’ve never been an anxious test taker. Even for other high-stakes tests I’ve taken in the past, I study well, I stay calm, and I stick to my plan. And it pays off. But this time, I couldn’t stay calm. Part of my anxiety was due to the pressure of performing well enough to be granted my teaching license, but I soon realized that this was not the true origin of my worries.

What began to scare me about becoming a special education teacher right now is the funding cap on students with disabilities.

How do I give my future students an appropriate, much less a brilliant education, when their education isn’t fairly funded?

That’s one answer I couldn’t find on this test.

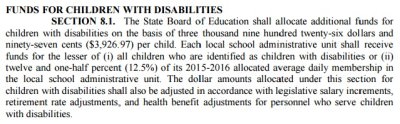

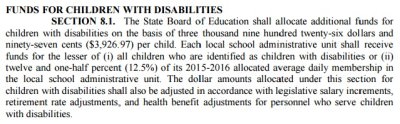

The proposed Senate budget calls for $3,926.27 per child with an identified disability attending public or charter schools, per school year. The last budget allocated $3,743.48 per child, so yes, there is an increase. Thank you, but it is not enough.

The greatest point of inequality in special education funding from the state is an arbitrary cap on per student funding at 12.5 percent that has been in place since the 1980-81 legislative session. Our state only provides special education funding for 12.5 percent of the student population in a given district. This cap was created with good intentions — to prevent over identification of students with disabilities and to ensure that funding remained somewhat balanced. The cap, put in place more than thirty years ago, has never been changed. Meanwhile, national rates of disability have risen to well over 12.5 percent.

Our policymakers inherited this problem, but we need them to change it. The world has changed. Our state has changed. What we know about educating these students has changed.

Our legislators have the power, and the responsibility, to change the cap. The ball is in their court now.

Jason Langberg wrote in an op-ed to Raleigh’s News and Observer that this cap is only limiting and penalizing districts with higher percentages of students with disabilities. He examines Stokes County Schools and the inequality they face due to this outdated cap.

“On April 1, 2014, Stokes County Schools had identified 1,136 SWD – approximately 20 percent of the total student population. Therefore, Stokes essentially didn’t receive any per-student state special education funding for about 506 students with disabilities.” – Jason Langberg, The News and Observer

It leaves me wondering what the schools, teachers, and families in districts like Stokes County are supposed to do to make up the difference. Yes, every child will still receive some level of funding from this categorical allotment. But it does not make it sufficient, and it does not make it equal.

Further, many districts that are above the 12.5 percent cap are also considered low-wealth districts. They may not have the community resources necessary to make up for what so many students are losing without adequate state funding.

In 2010, a study by Augenblick, Palaich and Associates, Inc. completed at the request of the North Carolina General Assembly examined the inequality of funding cap. The study recommended maintaining a cap on funding for students with mild and high prevalence disabilities, as this rate is fairly consistent across districts, but fully eliminating the cap for the less prevalent moderate and severe disabilities. With this modification, allocations would vary to meet the diverse financial needs of various disability categories while responding to the rates of moderate to severe disabilities in individual districts. This is an issue that could be changed this session.

The cap and per-child allocations are simply no longer adequate. They do not account for the growing rates of identification and placement in special education. They do not account for the disproportionately lower graduation rates of students with disabilities. They do not account for all we have learned about improving educational outcomes for our students with disabilities.

Teachers, administrators, school districts, and statewide services are doing all they can. And they’re making magic happen. Teachers pay out of pocket regularly to help their students — from snacks and crayons to pricey computer programs. They find creative ways to make up the difference, often by making their own sensory materials, adapted toys, and low-tech assistive technology devices. School districts do what they can to help families afford assistive technology devices and other tools when state funding and Medicaid may not be enough. DPI goes to great lengths to make sure every student with an identified disability is accounted for and receives their fair share. They spend much of their time educating families and professionals on how to provide the instruction for their students with disabilities, and how to effectively use whatever funding is provided.

At the end of the day, I know that our state’s teachers, administrators, families, and advocates will not let inadequate funding hurt the education of our students with disabilities. They will continue to work miracles with whatever funding they are given.

Our leaders have the power to start a statewide conversation about providing the best education possible for our students with disabilities in the 21st century.

It’s their turn to pass this test.

Editor’s Note: Many thanks to Philip Price at N.C. DPI who helped us understand the origins of the cap. For those of you that are interested, here is a summary of legislated changes for Exceptional Children since 1976-77.

Price says,

Children with Special Needs is a categorical allotment which supplements base/foundation State funding. The purpose of all categorical (supplemental) allotments is to enable a school district or charter school to design a program to utilize all available funds to assure that every child identified with disabilities receives the appropriate/identified services. Since the range of needed services range from none to extensive, the funding is designed to establish a level of funding sufficient to offer a complete program for all identified students. The 12.5 percent level provides a means for calculating the amount designed to supplement the base funding in order to serve exceptional children. For the most extreme cases, reserve funds exist that can be applied for to assure the high cost students receive the required services.

The key question is, is funding sufficient (base + supplemental + reserve) to offer the needed services for all children with disabilities? The question is not does every child receive funding. State funding is based on allotted ADM and the April 1 headcount. The federal funding is based on the December 1 headcount.