When we read that more students have been killed in U.S. school shootings this year than U.S. military personnel in combat operations — as reported in The Washington Post — there is a wave of suggestions on how to fix the problem. Last month, a student at a high school near Charlotte was fatally shot, with bullying identified as a factor.

When the headline is still fresh, there is a collective urgency for finding solutions. There is a spike in outrage and enough finger-pointing to go around, but it is time — and has long been time — to look beyond the statistics and the theories and examine the one element common to every act of violence: human relationships.

In response to the Parkland High School shooting, the N.C. House School Safety Committee has been holding meetings across the state to hear about the challenges schools face in implementing school-safety policies. Proposals have included adding a law-enforcement officer in every school, more counselors, social workers, and psychologists, while on the logistics side, limiting the number of school entry points.

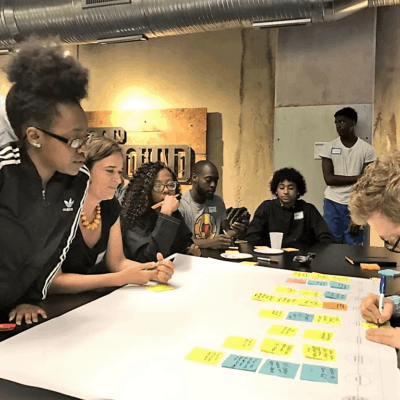

We must, however, also understand human relationships as a critical point of origin when considering school violence. Extensive conversations about relationships in school and the changes needed to provide more personalized and meaningful school experiences, can assist students’ academic, social, and personal lives but also their safety. While the immediate concern might be to prevent students from falling through the cracks, paying attention to relationships would benefit all students.

Most incidents of school mass shootings occur at the high school level, when students are at a challenging age and often dealing with multiple issues: transitioning to young adulthood; physiological and emotional changes associated with puberty; managing peer-group relations in person and on social media; coping with struggles at home, such as divorce and poverty; and interacting with students, possibly for the first time, from different cultural, racial, and socioeconomic backgrounds. These all factor into a student’s interaction with the world around them and their motivations and behavior.

Furthermore, as student safety and security have increased in importance, schools have become more focused on managing students, ensuring that they are in class and minimizing free time for engaging with their interests or exploring their surroundings. Students spend a large part of their day in this highly controlled environment, which, although steeped in punctuality and order, rarely addresses their interests or their social and emotional growth.

Apart from the tragic events at Sandy Hook Elementary, most mass school shootings have occurred in high schools with 1,000 or more students. Support for large high schools is often based on claims of greater efficiency, with such schools being able to offer a wider range of courses and extra-curricular options. However, not only is it easier for students to get “lost in the crowd,” but as far back as the 1970s, education reformer Ted Sizer raised concerns about high schools’ attempts to be comprehensive and their failure to offer a more personalized and meaningful learning experience.

In his research, Sizer described how students are seen by five or six teachers a day, all of whom know the student only through the lens of their academic subject; for example, as a math student. Rarely does anyone see the student as a “whole person.” In the aftermath of a violent incident, we ask, What signs did we miss? What was he or she thinking? But our students and society would be better served by this degree of attention before the next blood is spilled.

It is relationships that we need to pay attention to, specifically students’ social and emotional development, creating a more personalized high school experience and including a strong advisory program. Advisory programs generally feature a daily meeting with 15 students and a staff adviser who provides both academic and personal support. It often is the only place in school where a student is treated as a “whole child,” rather than “math student,” etc. The ongoing relationship with a caring adult and student connections within a group could reduce the likelihood of students considering acts of violence. Additionally, it may be in the advisory group that signs of potential violence are discovered, resulting in immediate and proper intervention.

While few likely would object to the idea that a good school attends to the development of the whole child, most high schools are evaluated solely on academic performance. Pressure has only intensified as entire schools are now graded from A to F. With three classes of 30 students each and the expectation that every student learns the required content, the average teacher, understandably, does not have time to get to know the “whole child.” And violence — as well as other serious issues — originates from the “whole child,” not the “math student.”

We must expand the criteria by which we evaluate high schools, and we must do so as if lives depend on it. Indeed, they do.