EdNC is exploring the experiences of young children from infancy to third grade in rural eastern North Carolina supported by a grant from ChildTrust Foundation. The research and reporting, which started at the end of last school year, will look at the issues children, families, and schools navigate at the start of kindergarten in Edgecombe, Nash, and Halifax counties.

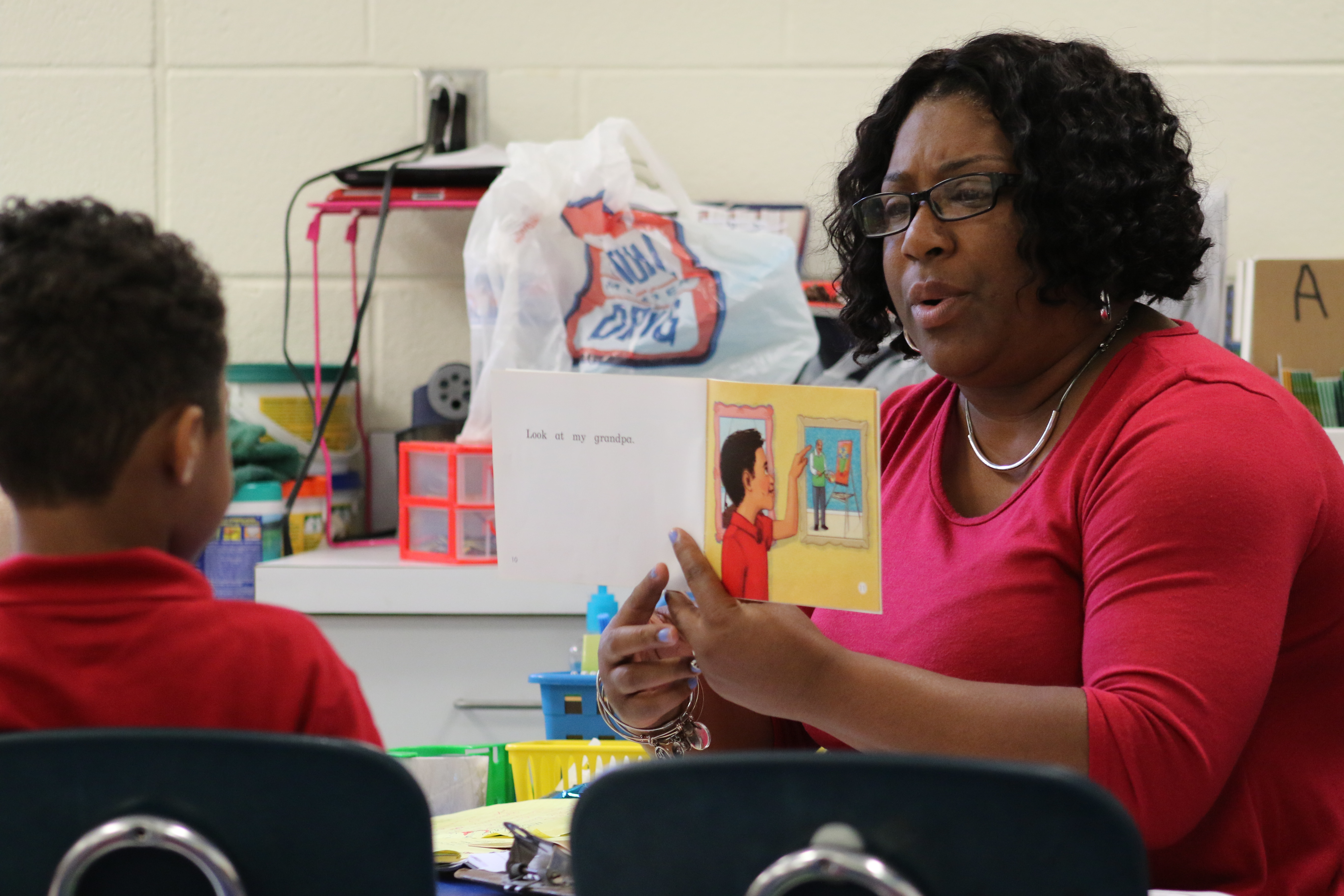

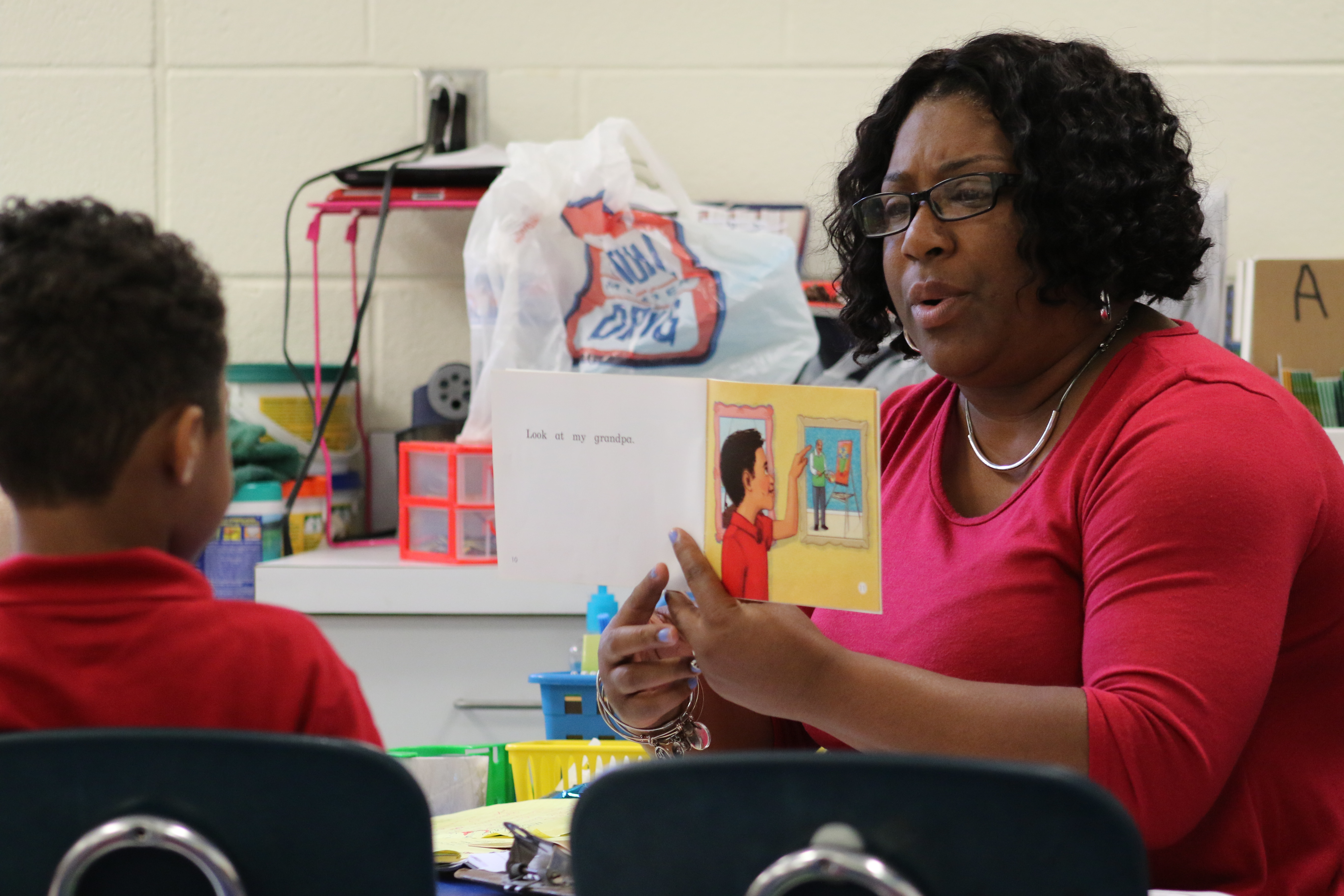

While reviewing her end-of-year student assessments in May, about half of the names on Dale Murray’s kindergarten class roster were in red. Murray, who has taught kindergarten at Bailey Elementary for more than 20 years, wished red meant something besides below-grade-level in reading.

“I don’t like it,” Murray said. “But I know I’ve done my job. I know they came in knowing nothing and I see how they’ve grown.”

Murray pointed to each red name and explained the student’s situation. Some students were English-learners. Some never went to preschool. Some will need special intervention and support because of developmental delays. Others had multiple circumstances that set them back. “It is a combination,” she said.

That combination of factors hindering a student’s learning during his or her first year of schooling is specific to the child. In rural eastern North Carolina — between the booming Triangle and the coast — those factors are often compounded by the stresses of poverty. Compared to North Carolina’s median income from 2012 to 2016 of $48,256, Nash County’s from the same period was $43,804, Halifax County’s was $32,549, and Edgecombe County’s was $32,398.

A recent study by researchers from The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and New York University of children growing up in poverty in the rural Southeast found that the depth and persistence of poverty during the first five years of life is related to lower language, academic, and executive functioning skills.

As Murray noted in her classroom, a student’s ability to perform on grade level by the end of kindergarten also has a lot to do with whether or not the child attended preschool and the quality of that program. “We can see growth, but they’re not where they would have been if they had had that initial push,” she said, referring to children who did not attend any kind of preschool before kindergarten.

Researchers at UNC’s Frank Porter Graham Child Development Institute have been evaluating NC Pre-K, the state’s public preschool for at-risk four-year-olds, since its inception in 2001. The group’s most recent study of 2015-16 NC Pre-K participation found children who attended the program had higher executive function related to working memory at the end of kindergarten and better math skills. However, NC Pre-K participation did not have a positive correlation with literacy skills by the end of kindergarten.

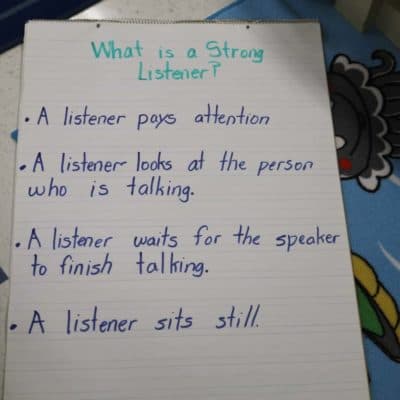

The difference between preschool and no preschool can be seen in basic skills and behaviors on the first day of kindergarten, Murray said. She said she expects children to be able to stand in line, stay in a seat, write his or her name, hold a pencil, cut with scissors, follow directions, and use the bathroom. North Carolina’s official standards for kindergarten readiness, which are documented in a Kindergarten Entry Assessment (KEA), are divided into domains that include “language and literacy development, cognition and general knowledge, approaches toward learning, physical well-being and motor development, and social and emotional development.” Teachers are supposed to observe children in these areas and use results to differentiate instruction.

In Edgecombe, Nash, and Halifax counties, quality of child care centers has greatly improved since the start of the century with support from Smart Start partnerships like the Down East Partnership for Children in Nash and Edgecombe, and Halifax-Warren Smart Start Partnership in Halifax. In 2016-17, the most recent data available from the N.C. Partnership for Children, 89 percent of Edgecombe children birth to five years old in regulated child care were in either a four- or five-star setting. In Halifax, 73 percent of young children in child care were in four- or five-star settings. And in Nash, 68 percent of young children in child care were in four- or five-star care. Those percentages have gone up from the following in 2000-01: 47 percent in Edgecombe, 53 percent in Halifax, and 48 percent in Nash.

Looking further into the academic lives of students, third-grade reading proficiency rates, which indicate student success in high school, were lower than the statewide rate for all three school districts in 2017. Statewide, 57.9 percent of third graders passed the End of Grade reading test by scoring either a 3, 4, or 5. According to North Carolina School Report Cards, scoring a 3 indicates the student is on grade level and scoring a 4 or 5 indicates career and college readiness. In Nash-Rocky Mount Public Schools, 40.5 percent of third graders in 2017 passed the test. In Edgecombe County Public Schools, 32.5 percent of third graders in 2017 passed the test. And in Halifax County Public Schools, 38.2 percent passed the test.

The quality of early experiences is being tied to the health and economic development of entire communities. Henrietta Zalkind, executive director of the Down East Partnership for Children, which serves as the preschool infrastructure for Nash and Edgecombe counties, presented in July at Energizing Rural North Carolina on the return on investment in children’s early years.

“Early childhood is really all of the things that happen between when a child is conceived and by age eight,” Zalkind said. “And the reason that we focus on those early years is because that’s when you develop the academic and the social skills and the problem-solving skills, and you have heard over and over again, that that’s what business needs. That’s who the workforce of tomorrow is gonna be. By age eight, kids should have learned to read so that they can read to learn.”

That turning point — from learning to read to reading to learn — is one often repeated by early education advocates. Third-grade reading proficiency’s correlation with high school completion has dominated statewide conversations across the state’s education, government, nonprofit, and business spheres. Political leaders on both sides of the aisle have used early literacy as a talking point. In July 2012, the General Assembly started Read to Achieve, legislation that gives extra support to children who are not reading on grade level by the end of third grade.

The Republican-dominated General Assembly included plans in their 2017-19 biennial budget for an additional allotment to NC Pre-K of $9.35 million for 2019-20 and $18.7 million for 2020-2021. And then in February 2018, lawmakers added even more funds to eliminate the NC Pre-K waiting list altogether by 2020-21. Democratic Governor Roy Cooper spoke of early childhood’s importance at Energizing Rural North Carolina answering a question from EducationNC.

“When you’re talking about early childhood, the evidence is overwhelming that kids who have early childhood and pre-K succeed at a much faster rate than those that do not,” Cooper said. “So this is an early investment. There’s a reason why a number of CEOs of tech companies came to the General Assembly to lobby for pre-K. Because they saw the importance of early childhood education.”

That group of CEOs came before the legislature in February 2017, headed by SAS CEO Jim Goodnight, and presented economic arguments of early education and early literacy.

Since 2015, the non-profit North Carolina Early Childhood Foundation has spearheaded both a campaign across the state to promote more reading proficiency in low-income communities and a cross-sector and data-driven Pathways to Grade-Level Reading initiative to outline shared measures and goals for children from birth to eight years old.

Superintendent of Public Instruction Mark Johnson, who heads the state education department, has repeatedly focused on early literacy since his 2016 election, using Read to Achieve funds for K-3 literacy materials, professional development programs, and technology since March.

The B-3 Interagency Council was formed by statute last year as an attempt to enhance collaboration between the governing bodies that oversee early childhood education (the Department of Health and Human Services) and the state’s K-12 system (the Department of Public Instruction) and smooth transitions between the systems.

All of this cross-sector and bipartisan momentum around early childhood education begs the question: What is happening in the rural classroom? Over the course of the coming months, EdNC will spend time in the following three elementary schools in three counties to look at how they teach their youngest learners and what those learners need.

Coker-Wimberly Elementary School

About 72 percent of the 284 students at Coker-Wimberly Elementary School in Edgecombe County were economically disadvantaged, according to the school’s 2016-17 state report card. In 2016-17, the school received an F performance grade, which is calculated by the state using a formula of 80 percent achievement and 20 percent student growth. In the same school year, Coker-Wimberly did not meet the state’s growth standards. In 2017, 23.4 percent of third graders made a 3, 4, or 5 on the End of Grade reading assessment.

This school year, about 65 percent of Coker-Wimberly students are black, 20 percent are Hispanic, and 9 percent are white. The school is headed by Katelin Row, a graduate of N.C. State University’s accelerated principal preparation program called NELA. Using flexibility granted to the school through a restart status, Coker-Wimberly started at the beginning of last week, which is earlier than most North Carolina schools.

Through that same status, Row has implemented “opportunity culture,” a staffing approach that creates higher-paid positions for highly-effective teachers to reach more students. There are multi-classroom leaders for both reading and math in early grades that provide extra support and coaching for kindergarten teachers. Row is hopeful that the school’s strategy will raise student performance.

For the second year, Coker-Wimberly kindergarteners switch classes, which usually does not happen until later grades. This subject specialization is aimed to help teachers be able to focus on the specific needs of students in each subject but can prove difficult when it comes to classroom management.

Bailey Elementary School

About 79 percent of the 626 students at Bailey Elementary School in Nash County were economically disadvantaged, according to the school’s 2016-17 state report card. In 2016-17, the school received a C performance grade. The school also met the state’s growth standards that year. In 2017, 45.3 percent of third graders made a 3, 4, or 5 on the End of Grade reading assessment.

According to Principal Mary Jones, about 200 Bailey students last year were English-learners. The surrounding community is heavily agricultural and some migrant families with seasonal jobs have students attending Bailey. Around 50 percent of Bailey students last year were Hispanic, 33 percent were white, and 13 percent were black.

Jones is continuing a dual language program this year, where both native Spanish and English speakers are taught in Spanish. The kindergarten class from last year will move with its teacher up to first grade this year. The program uses Participate (formerly known as VIF) to employ teachers from Spanish-speaking countries to teach at Bailey.

Scotland Neck Elementary School

About 85 percent of the 224 students at Scotland Neck Elementary School in Halifax County were economically disadvantaged, according to the school’s 2016-17 state report card. In 2016-17, the school received a D performance grade. The school also met the state’s growth standards last year. In 2017, 36.2 percent of third graders made a 3, 4, or 5 on the End of Grade reading assessment.

Last year, 86 percent of students were black, 10 percent were Hispanic, and 4 percent were white. A new principal this year at Scotland Neck, Benjamin Eustice has been stunned at the level of parental involvement and community engagement he has seen so far. During the summer, Eustice was surprised that 70 out of 85 students who needed extra support showed up for optional remediation courses.

Eustice has had difficulty filling teacher vacancies during his first year. He said he is focused on creating a positive and proactive mindset within the classroom in the coming year to reduce a physical violence problem he has noticed.

“My focus will be creating that whole-child learner, not just somebody who’s good at math, not just somebody who’s good at reading, but somebody who does everything and is involved in everything — and you have a strong student based on their beliefs and not only their smarts,” Eustice said. “Again, creating a leader.”

The importance of this first year, Coker-Wimberly kindergarten teacher Taylor McNab said, can be seen in children’s lives years later. McNab taught math to fifth and third graders before transitioning to kindergarten last school year.

“Coming from fifth grade and third grade actually helped me, because I saw what they didn’t have, so now I kind of know what to lay down more,” she said. “I had third graders and fifth graders who couldn’t add double digits. And I’m like, ‘Okay, they obviously missed something.’ It was really cool coming down, because you get to really focus on what they missed and meet them where they’re at.”

Continue to check back at EdNC.org to delve into the stories of kindergarteners and their families, schools, and communities.