As spring melted into summer in 1973, the General Assembly converted a pilot program into full-day kindergartens for five-year-olds in public schools across the state. With the state then in relatively sound fiscal health, Republican Gov. Jim Holshouser and a Democratic-majority legislature faced a classic decision:

Is it better to “give back’’ a modest amount of money to each state taxpayer through a tax cut, or do you spend revenue as a democratic society to strengthen the life-prospects of young people?

Holshouser and Democratic legislators rejected calls for a tax cut, and funded statewide kindergarten. Now, North Carolinians consider kindergarten a given, as integral to public education as the 6th grade.

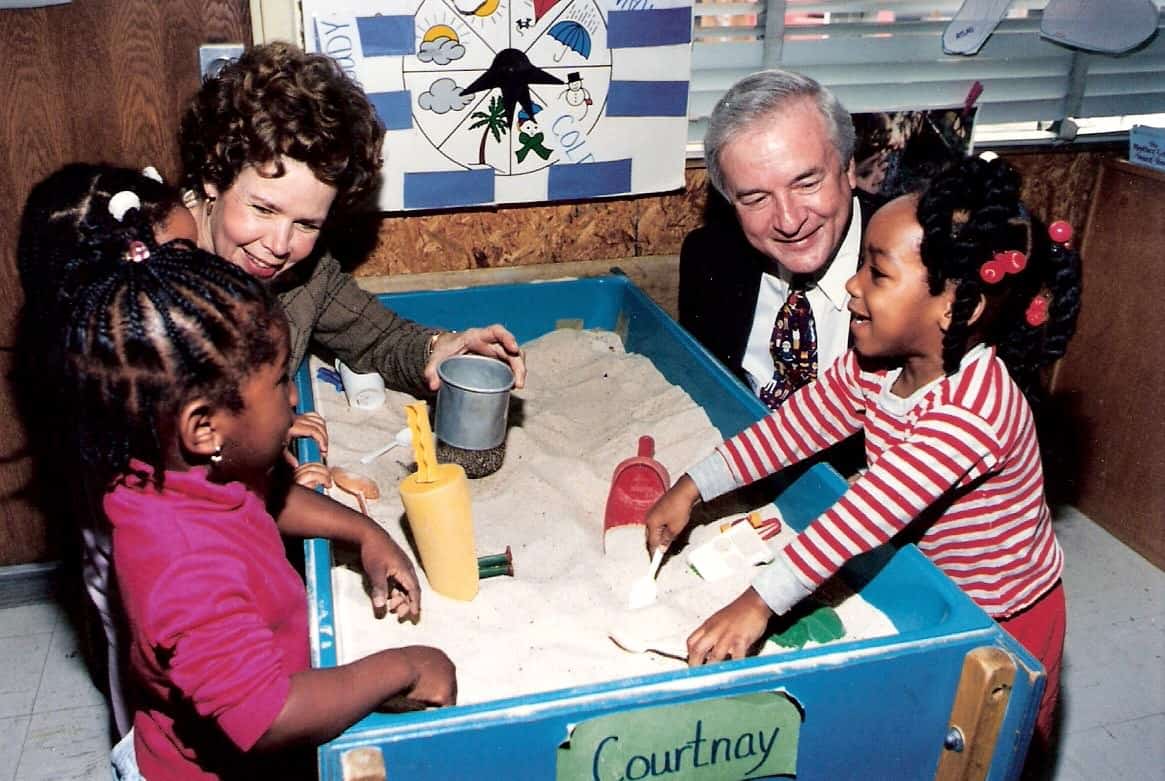

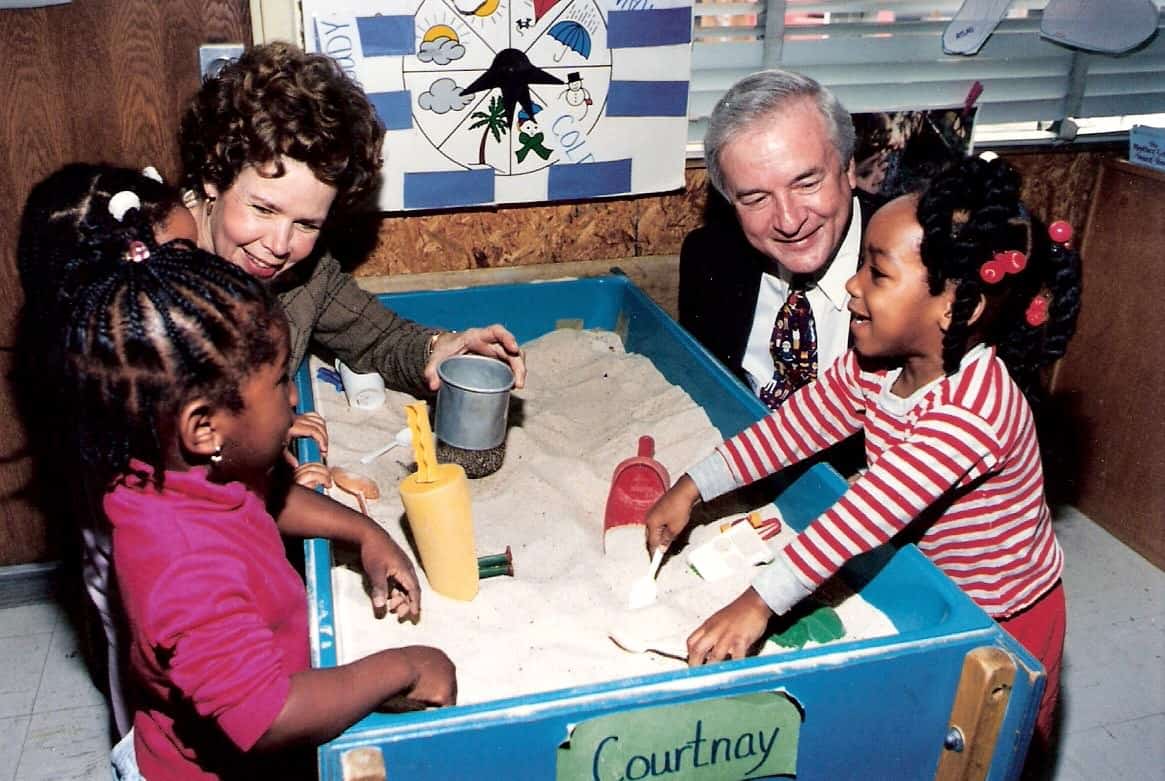

Twenty years later, North Carolina expanded its efforts to enrich early childhood with the creation of what became known as SmartStart, targeted at children 0 to 5 years of age. At the urging of Democratic Gov. Jim Hunt, the General Assembly established the North Carolina Partnership for Children, which, in the competitive two-party temper of the times, Hunt designed to appeal to Republican sensibilities. SmartStart did not create a new state bureaucracy, but rather the partnership is a nonprofit corporation that channels state money into local nonprofit organizations to finance child care, immunizations and an array of health and family services.

Nearly a decade later, Democratic Gov. Mike Easley brought about another expansion in early childhood education through what he branded More at Four. Initiated in 2001, More at Four targeted at-risk four-year-olds and placed them in preK classrooms in schools, as well as in high-quality private child care. To cope with a recession and to fund education-related initiatives, Easley coaxed a Democratic-majority legislature into adopting a state lottery and to enact a one-cent sale tax increase.

In 2011, a Republican-majority legislature changed the name of More at Four and moved it out of the Department of Public Instruction. Now, it’s called North Carolina PreK, administered in the Department of Health and Human Services.

But a name-change and a bureaucratic shift are less important than the sense that, after a period of briskly jogging forward, North Carolina has lately been running in place in its support for early childhood education. The legislature has sustained SmartStart and NC PreK, along with child-care subsidies. And yet, state appropriations for early childhood programs have not returned to peak-year levels, and the state has relied more on federal funding sources.

With these distinct programs complementing each other, North Carolina can claim a rather substantial achievement over the years in expanding from the development of statewide kindergartens in the mid-1970s.

“North Carolina has been a national leader in developing initiatives designed to address childhood disadvantages,’’ says a group of Duke University scholars in a recent paper.

In their research, the scholars – Clara G. Muschkin, Helen F. Ladd and Kenneth A. Dodge – found “that access to early childhood programs in North Carolina significantly reduces special education placements in third grade.’’SmartStart reduced placements by 10 percent, More at Four by 32 percent at 2009 funding levels, they found. And, they reported, the state would spend less on early childhood programs than on special-education disabilities in elementary school.

In the view of Tracy Zimmerman, executive director of the NC Early Childhood Foundation, the county-level nonprofits network of SmartStart represents a “powerful tool that we should be fully utilizing.”

“SmartStart is our state’s infrastructure in every community,” she said, as she was preparing for the negotiations between House and Senate over the 2015-17 state General Fund budget. “It’s the envy of every state.”

In a mid-April briefing for the Joint Health and Human Services Committees, the Legislative Fiscal Research Division cited the State of Preschool evaluations by the National Institute for Early Education Research over the 40 states that offer preK. It found that North Carolina was one of four states that met all 10 benchmarks evaluated.

Early education advocates hope for marginal advances, and minimal back-sliding, in funding and eligibility criteria in House-Senate negotiations.

Not so long ago, North Carolina seemed in the vanguard of a movement toward universal four-year-old preK.

Now, whereas North Carolinians expect public schools to offer kindergarten to five-year-olds, early childhood programs have not yet become so naturally embedded.

A footnote: As I was thinking ahead to a column on early childhood policy, David McBriar, a Franciscan Friar with long service as pastor of Catholic churches in Durham and Raleigh, alerted me to a comment by Dietrich Bonhoeffer, a Lutheran theologian who resisted the Nazis and Hitler, and was executed in 1945. I found two versions, similar but distinct:

“The ultimate test of a moral society is the kind of world that it leaves to its children.”

“The test of the morality of a society is what it does for its children.”

Whether he said one or both of these comments, Bonhoeffer left us a potent “test’’ to ponder.