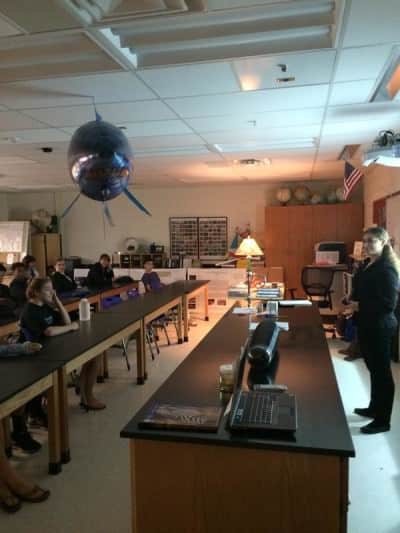

Everyone grows into a suit, and the best STEM students are no exception. I watched as four students in jackets one size too large stood addressing a rapt audience, explaining how their science experiment worked.

“Science experiment” may be too loose a term for what they’ve done: evoking images of baking soda volcanoes or potato batteries. These students are explaining how slime mold moves through a maze when light is placed at one end. The results?

“[Slime mold] can be used as a biological computer,” one of the students says.

This is the Thomas Jefferson Symposium to Advance Research (tjSTAR), an annual, year-end cap to the projects students at Thomas Jefferson High School for Science and Technology have been undertaking in labs and classrooms at the Northern Virginia STEM school.

Biological computers are just the tip of an academic iceberg, covering everything from neurology to mechanical engineering and music composition to solar power. These are projects, but they’re also a selection of the academic paths students at Thomas Jefferson can choose from.

The focus on academic achievement has made Thomas Jefferson one of the most well regarded schools in America.

The 2015 US News school rankings awarded it number one high school in Virginia, number three in the country, and number two in the STEM division.

Principal Evan Glazer attributes that success to the school’s focus on rigor at all levels. Last year, 2,900 students applied to Thomas Jefferson for around 480 open seats. Applicants are judged based on their middle school records, testing results, essays, and teacher recommendations. Students are achievers before they even set foot in a high school classroom.

Once enrolled, everyone is held to the highest standards possible. Glazer says setting the school’s expectations above those of advance placement courses helps students pass those exams. The school’s mean AP score is 4.5 out of a possible 5.

As a Regional Governor School, Thomas Jefferson pulls in students from six counties in Northern Virginia, just south of Washington, DC. Drawing from 40 to 50 high schools in the area, it’s an oddity among its neighbors.

While technically part of the Fairfax County School system, Thomas Jefferson crosses a number of borders in its enrollment. That can make it difficult for the school to find allies to help fund its endeavors. On the other hand, everyone who feeds into the program wants it to succeed, giving it plenty of potential supporters across the community.

“As a regional school, everyone looks out for us and no one looks out for us,” Glazer says. “We have to roll up our sleeves and very carefully plan out how we can make the most out of each dollar.”

Like any school, Thomas Jefferson is constrained by its finances. Much of the work that Dr. Glazer does is focused on building relationships with other organizations, in order to give students opportunity beyond the limits of budgets.

This is the crux of Thomas Jefferson’s success; building relationships.

At tjSTAR, the gym is filled with students and companies, a reflection of the work that Glazer and his teachers have done. Honeywell, the Department of Defense, Leidos, and Japan Science and Technology Agency have all sent representatives to court the future of American science.

Thomas Jefferson has launched a satellite with NASA, garnered grants from Google, and partnered with Virginia Tech on DNA research. It’s these sorts of collaborations that give the school reach beyond its fiscal means.

As a Governor’s School, Thomas Jefferson gets a 10 percent bump in its funding, but it’s not enough to cover all the programs its faculty and students want to pursue. Glazer spends a good chunk of his time hunting down new partners, engaging in the tech community, and working on grants.

“Finding resources is my call to action,” Glazer says.

He also encourages all faculty members to be involved in their own scientific circles, seeking out new ways to get students involved around the country. That gives Thomas Jefferson more avenues to explore and more ways to challenge its students.

“Part of the goal is to develop opportunities for students that enable them to expand the program,” Glazer says.

Programs like the STEMbassadors and the Jefferson Collaborative Inquiry and Research Network (JCIRN) give students chances to volunteer locally and build connections with Thomas Jefferson alumni, corporate partners, and the local community. Those programs also give students an important connection to the outside world.

The level of dedication demanded by Thomas Jefferson can make school an all-consuming affair. The hallways are littered with posters reminding students to get enough sleep and to take care of themselves.

“We don’t have a representative sample of the population,” Glazer says.

Working in the community acts as an important reminder that the rest of the world is made up of very diverse people. Understanding those differences can be just as important to success later in life as the scientific knowledge found in the classroom.

Volunteering isn’t the only outside activity that contributes to STEM success, though.

“What you do with your kids doesn’t matter nearly as much as who you are,” Glazer told the STEM Symposium earlier this year, when discussing getting children interested in STEM. “It’s those values that you demonstrate at home that ultimately have the highest impact on student engagement.”

The results have been hard to argue with.

Aside from being the first high school to build a satellite, dominating the school rankings, and building ties in the community, Thomas Jefferson is pumping out incredible, personal success stories.

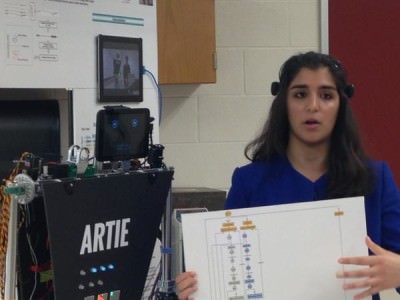

This year, senior Pooja Chandrashekar was accepted to fourteen schools. Stanford, MIT, Duke, the University of Virginia, the University of Michigan, and Georgia Tech. Oh, and all eight of the Ivy League universities.

In 2013, the school sent ten students to Princeton, eleven to MIT, and nineteen to Cornell. It’s a record that few, if any, could hope to surpass.

Glazer said that these kind of results don’t come from some mystical formula or fistfuls of cash – it’s rigor and dedication.

The four students in their long sleeved and broad shouldered jackets weren’t the result of a financial equation. They all had a dedication to science and an understanding of the incredibly high bar that Thomas Jefferson sets for its students.

One speaker at tjSTAR told me that he loved talking to the students because he never had to dumb anything down. They care about the topics he talking about and they want to know more.

As I left the building, I walked past an empty lab and poked my head in. A woman inside sitting at a computer turned and smiled.

“Are you a teacher here?” I asked her.

“No,” she said. “This is my fun little retirement job. I used to be an engineer.”

The lab was filled with glass tubes and clean surfaces, and it had that high school lab smell common across America. A University of Florida college pennant hung on the wall along with safety papers and notifications.

“What makes it fun?” I asked.

“The kids,” she said. “They’re all so motivated. It makes all the difference.”

Those four kids didn’t study slime mold because it was easy, or cool, or because they thought they would get a better grade. They did it because they were genuinely interested in what would happen when you put slime mold in a maze and shone a light on it.