As we mentioned recently, a state legislative committee is discussing possibly huge changes to the way K-12 schools are funded.

The Joint Legislative Program Evaluation Oversight Committee met November 16 and tentatively decided to move forward with drafting legislation that would create a Joint (House and Senate) Task Force to examine whether the state should move from a funding system based on allotments to one that uses a weighted student formula.

“There are very few people…that truly understand how our funding system for public education works,” said Rep. Craig Horn, R-Union, a co-chair of the committee. “And we’re all very much aware of the challenges of appropriate funding for public schools.”

How are schools funded?

To understand the significance of this, it’s important to first understand both how North Carolina currently funds its K-12 schools, and how a weighted student formula would do so.

According to the presentation at the November meeting, in Fiscal Year 2014-15, the public school system was funded at about $12 billion, $8.4 billion of which was strictly state money.

That $8.4 billion is the money this discussion is concerned with.

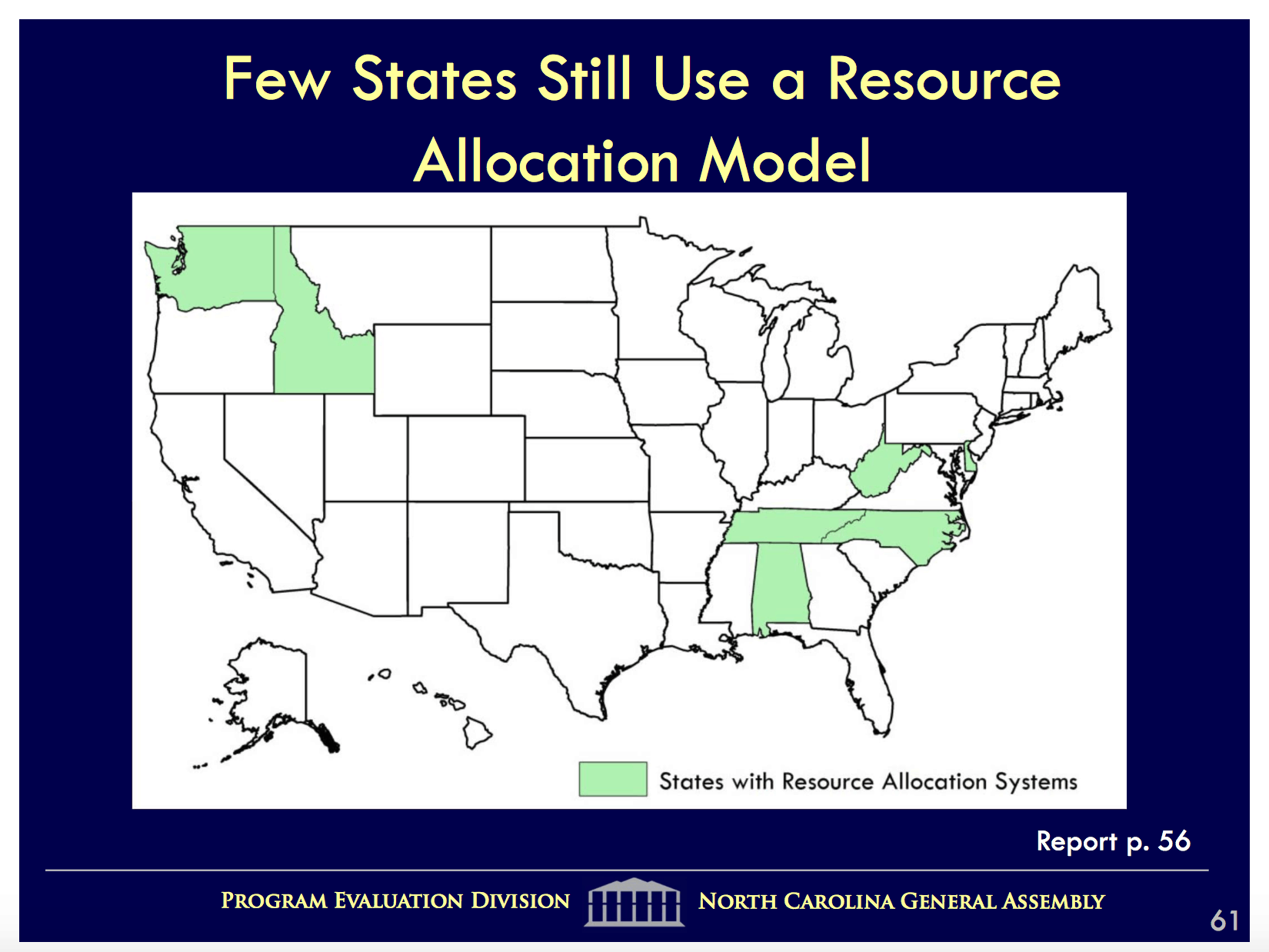

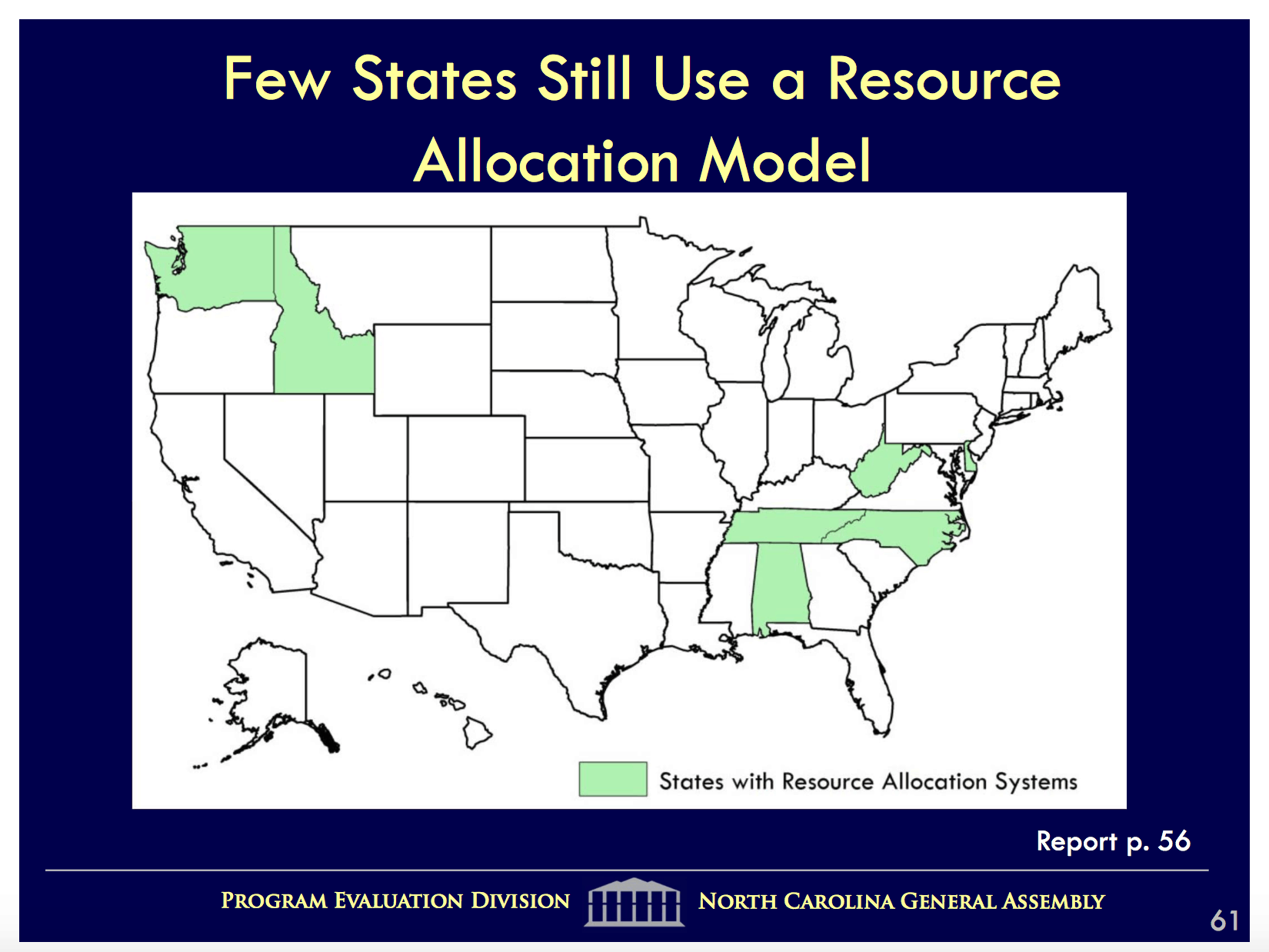

Presently, the state doles out those funds using a series of allotments — 37 in total. The allotments are essentially line items. X amount of money for classroom teachers, Y amount of money for school building administration, etc… This is called the Resource Allocation Model.

It’s complex, and the whole point of the November meeting was that there are serious issues with that system. We will get to those problems later.

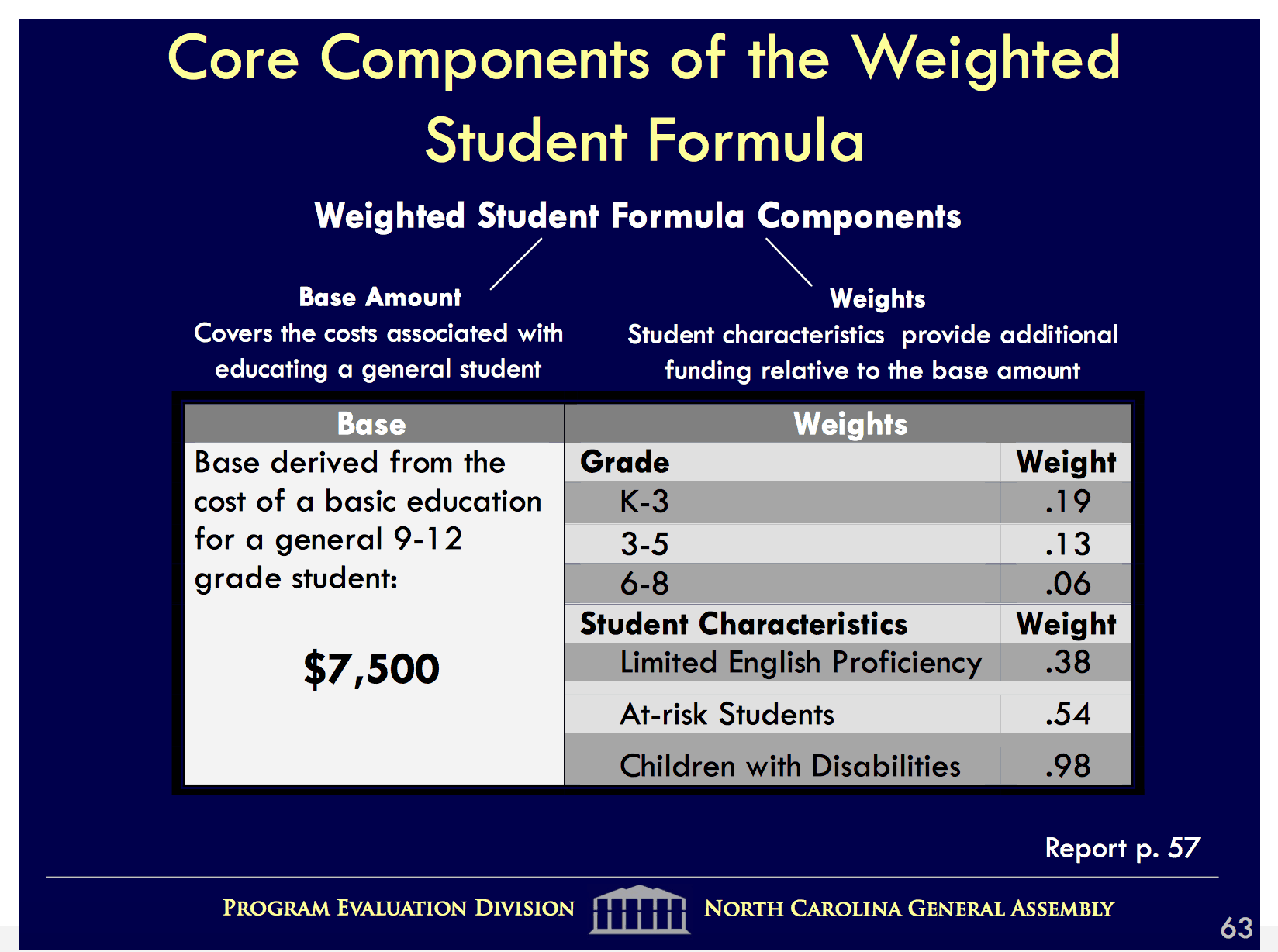

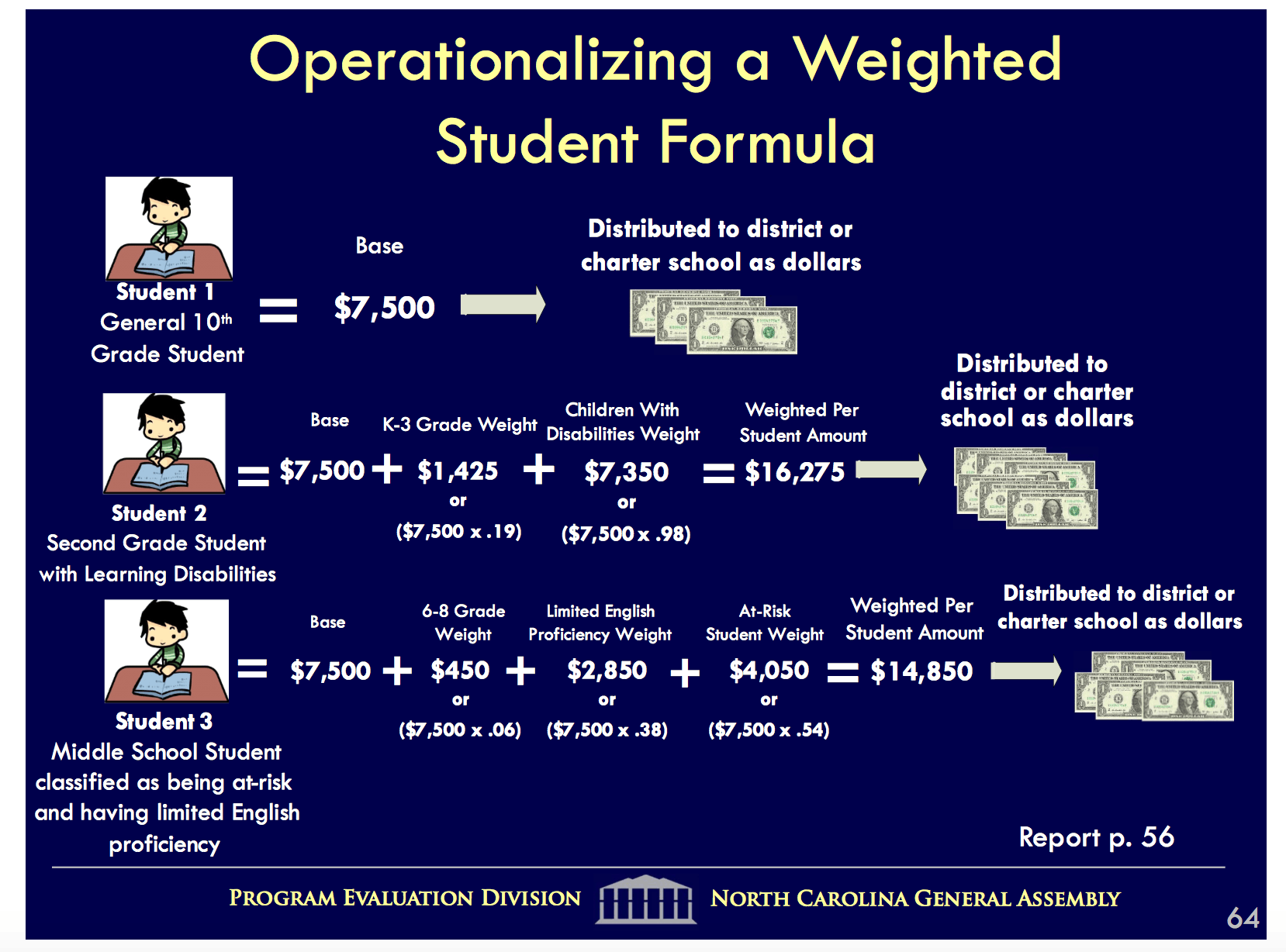

The weighted student formula is much more simple. Under this formula, the money would be based on the student. Basically, the state would allot a base amount of money for each student in the state. The arbitrary example given at the November meeting was $7,500 (note: that is not the funding number being proposed, simply a number picked to use in an example).

Now, the distribution of funds changes depending on the type of student. A normal student with no special needs affords the school $7,500. But let’s say you have a student who is K-3. Well that student would get an additional .19, or $1,425, of that base of $7,500. If that student has disabilities, he or she would get an additional .98 or $7,350 of that initial $7,500. When all the numbers are added up on that student, the school gets a total of $16,275 for that one student.

So basically, schools get funded based on the number of students. Normal students get the base $7,500, and extra money is allotted depending on any extra needs students might have.

Check out these slides from the chart to get a better handle on how this might work.

A few more things

A few more things you should know before we get into the problems unveiled in the report to the legislature on November 16.

First, North Carolina is one of only a very few states in the country that uses the kind of model we use. Check out this map that shows where in the country states still use the “Resource Allocation Model.”

Second, this isn’t the first time North Carolina has discussed the possibility of making these very changes.

Back in 2010, the General Assembly conducted similar research, resulting in a 2011 report that closely mirrors the findings of the report presented November 16. For a variety of reasons, that report went nowhere.

Terry Stoops, director of education studies at the John Locke Foundation, said that the recession, along with the change in power as Republicans took over the General Assembly in 2010, both contributed to the report being shelved. But even without those factors, he said it didn’t seem as though anybody had much interest in effecting wholesale change.

“I didn’t get the sense even amongst the Democrats that there was much of an appetite for tinkering with it,” he said. “It was shelved very quickly. There wasn’t much talk of taking the recommendations in the report and going forward.”

Of course, the situation is different now. Republicans have been in power for six years and the great recession is no more, though its effects linger.

The Committee voted November 16 only to have staff create draft legislation that would create a Joint Legislative Task Force that would study the feasibility of moving to a weighted student system. And there certainly wasn’t a consensus among the attendees that a move to that system should happen; or if it did happen, that it should happen fast.

Some, like Rep. Becky Carney, D-Mecklenburg, said she wasn’t convinced we shouldn’t just make changes to our current system.

And Rep. Marvin Lucas, D-Cumberland, said the Committee should maybe slow things down.

“I’m not quite sure that we ought to move with the expeditious speed,” he said. “This is a tremendous challenge, especially when we consider the current make-up of the task force.”

Carney and Lucas were concerned about the task force being made up solely of legislators.

“It’s going to be a political battle,” Carney said. “But I think if we have other people at the table than just the legislators, it might help us.”

While it sounded like the draft legislation would stick with just legislators, Horn and others did say that the Task Force would likely spend a lot of time consulting with other groups and stakeholders.

Horn himself was fairly adamant that the Task Force, at least, should get off the ground and get to work.

“We can choose to, as we often do, do nothing and continue down our merry way,” he said. “But that’s not the message the voter is sending us in this state or across the nation.”

The Problems

So why all the angst? What’s wrong with the current system? The report presented November 16 displayed 12 findings that indicate severe dysfunction in the current funding model.

The presenter, Sean Hamel, principal program evaluator of the General Assembly’s Program Evaluation Division, took the legislators through each finding. They were divided into two groups — Allotment-Specific Issues and System-Level Issues. So let’s list them one by one:

Allotment-Specific Issues

Finding 1: The structure of the Classroom Teacher allotment results in a distribution of resources across LEAs that favors wealthy counties

Finding 2. The Children with Disabilities allotment fails to differentiate funding based on the instructional arrangements or setting required and contains a funding cap that results in disproportionately fewer resources going to LEAs with the most students to serve

Finding 3. The allotment for Limited English Proficiency (LEP) contradicts the principles of economies of scale and contains a minimum funding threshold that results in some LEAs serving LEP students without funding

Finding 4. The allotment for small counties is duplicative and not tied to evidence regarding costs of operating small districts

Finding 5. The Low Wealth allotment formula relies on a factor that does not accurately assess a county’s ability to generate local funding

Finding 6. The allotment for disadvantaged students provides disproportionate funding across LEAs

Finding 7. Funding for central office administration has been decoupled from changes in student membership, creating an imbalance in the distribution of funds

For more details on these issues, go here for a summary of the report, as well as the final report and other documents related to the meeting.

Also, here is video of Hamel’s presentation that includes his description of the problems listed above.

Here is video of questions from legislators on that portion of Hamel’s presentation.

System-Level Issues

Finding 8. North Carolina’s allotment system is opaque, overly complex, and difficult to comprehend, resulting in limited transparency

Finding 9. Problems with complexity and transparency are exacerbated by a patchwork of laws and documented policies and procedures that seek to explain the system

Finding 10. Allotment transfers—a system feature intended to promote LEA flexibility—hinder accountability for resources targeted at disadvantaged, at-risk, and limited English proficiency students

Finding 11. Translating the allotment system for funding LEAs into a method for providing per-pupil funding to charter schools creates several challenges

Finding 12. Using a weighted student formula is feasible and offers some advantages over the present allotment system, but implementation would require time and careful deliberation

Here is video from Hamel’s presentation regarding the problems listed in this section.

And here are questions from legislators on those issues, as well as the discussion and vote to move forward on draft legislation creating a task force to study the weighted student formula.

Legislators also discussed the possibility of making changes during the next session of the General Assembly to address some of the specific findings in the report related to the current funding system. That could happen independent of the task force studying the feasibility of the weighted student formula.

The Joint Legislative Program Evaluation Oversight Committee will meet again in December to take up the draft legislation creating the task force, and perhaps even vote on its creation.