The Ghost of Christmas Present takes Ebenezer Scrooge on a tour to see how people barely making ends meet nonetheless celebrate the feast. The episode ends with a haunting and provocative scene.

The ghost appears to have aged, and Scrooge notices “something strange and not belonging to yourself’’ under the ghost’s clothing. Out come two children, “wretched, abject, frightful, hideous, miserable.”

“This boy is Ignorance,” says the ghost. “This girl is Want. Beware them both, and all of their degree, but most of all beware the boy, for on his brow I see that written which is Doom, unless the writing be erased…”

Charles Dickens’ A Christmas Carol is a long-lasting work of fiction, not an education policy paper. Still, it’s fascinating that Dickens’ linked Ignorance and Want — and that he had the ghost emphasize the boy-Ignorance somewhat over the girl-Want.

Dickens did not elaborate, and the novel moves promptly on to the Ghost of Christmas Yet to Come. Still, did he not see clearly that society can’t reduce want without shrinking ignorance?

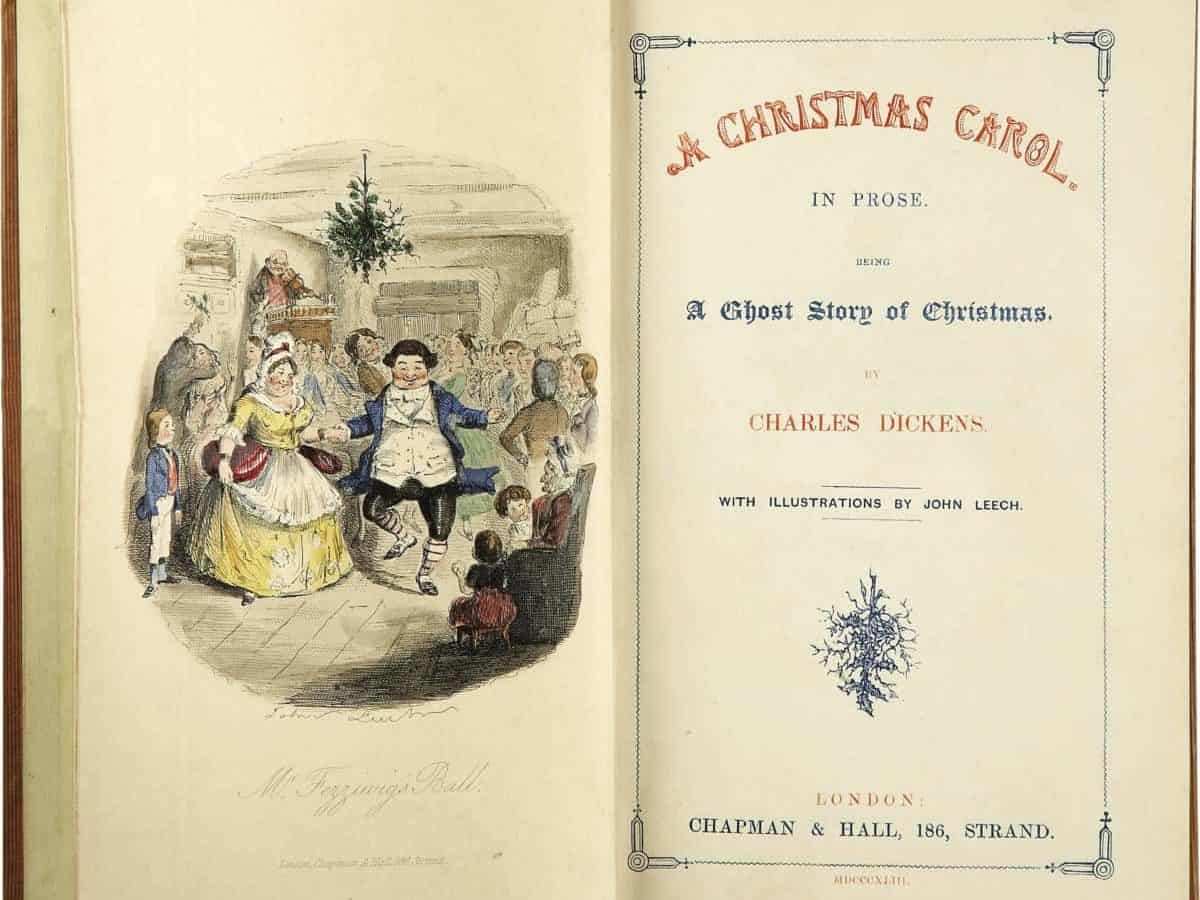

A Christmas Carol was published in December 1843, in early Victorian Britain, a period in which sons of wealthy, but not poor, families had opportunity for school-education, while girls were educated at home if at all. Six years earlier in the United States, Horace Mann had launched the common school movement that gave rise to public education across the nation.

Of course — and thankfully — Americans do not face the depth of want and ignorance that Dickens observed in 1840s London. And yet, a tight linkage remains between schooling and the poverty of today’s America. The modern economy makes some education beyond high school — in a community college or a university — an increasing imperative for attaining a middle-class standard of living.

Poverty imposes a heavy burden on schools. In North Carolina and elsewhere, half or more of public school students qualify for free and reduced-price lunch, an indicator of their households in financial stringency. As North Carolina’s school-grading system illuminates, achievement suffers in classrooms with large clusters of poor children.

Schools are also instrumental in fighting poverty. But they are not the only instrument. Poverty arises not only from lack of adequate education but also from joblessness, low wages, neighborhood conditions, and ill-health. And thus feeding the hungry, treating the ill, clothing the naked, and sheltering the homeless require an array of private and public deeds.

Drawing inspiration from sacred as well as such literary stories as A Christmas Carol, Americans propel themselves during this season to donate cash to charities and to collect food, coats, and toys to give to families in need. Volunteerism is wonderful, but meeting the needs also requires institutions — non-profits, philanthropies, religious congregations, civic clubs, and more to empower volunteers and to sustain efforts to reduce want across all 12 months. Throughout the year, it is awesome to behold volunteers who serve food in soup kitchens, who spend nights supervising shelters and treating the ill in community clinics.

To do social services well also requires institutions of democratically-elected, tax-supported government — and chief among those institutions are public schools, colleges, and universities. Schools fight lack-of-money poverty by equipping people with knowledge and skills. They fight political anemia and coarseness by endowing citizens with the ability to judge well in their exercise of democracy.

And schools fight the debilitating poverty of ignorance that saps the human spirit. Addressing the plight of the boy-Ignorance makes life better both for him and for the girl-Want.