|

|

When Elizabeth Thomas came to Jacksonville from Kinston in 1981, she could not find child care for her toddler. It was an overwhelming process that brought her to tears, Thomas said.

“And I’m not a crier,” Thomas, a retired educator, said to a room full of community leaders last week at the Jacksonville Onslow Chamber of Commerce, assembled for the launch of a local child care task force.

The group’s goal is to generate new ideas to address the same problem more than four decades later: a shortage of high-quality, affordable care.

“I’m like, oh my goodness, here we are, and we’re still pretty much the same way we were 40 years ago,” Thomas said.

The county, which has the highest birth rate in the state, has lost 32% of its licensed child care in the last decade, according to a meeting presentation.

However, it is also home to “the number one system in the country” for high-quality child care, said Dawn Rochelle, CEO of One Place, a nonprofit that serves young children and families as part of the statewide Smart Start network. “It’s called the military child care system.”

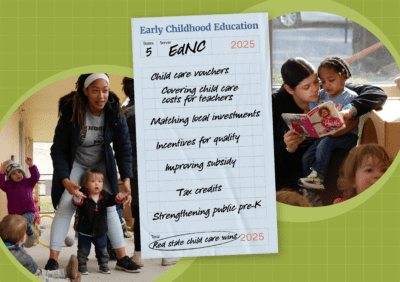

![]() Sign up for Early Bird, our newsletter on all things early childhood.

Sign up for Early Bird, our newsletter on all things early childhood.

The task force will meet with community members in various sectors over the coming months and present a report in April. Its challenges and opportunities are both commonplace across the state and country and specific to its local context.

“The uniqueness of being a military community in eastern North Carolina that is disaster-prone… I think we have a different story, not only for ourselves to learn more about, but I think that we also have a different story that can be shared,” Rochelle said. “…So how do we make the best of who we are and get other people to support us even more?”

Providers across the state have been calling for state investment to continue to operate in recent legislative sessions, with politicians on both sides of the aisle and business leaders joining their calls. Gov. Josh Stein created a task force this March — the same month that grants stabilizing the industry ran dry — to identify sustainable solutions. A state budget stalemate has resulted in no additional state funding to strengthen or expand child care.

Families in Onslow County are younger and having more children than in other places in the state. The county’s fertility rate from 2019 to 2023 was 90.1 births per 1,000 females ages 15 to 44. The statewide rate over the same period was 57.1. The average age of mothers in the county is also lower than the state average, with about 40% of mothers who were 18 to 24 years old from 2019 to 2023, compared to 23% statewide.

The county’s available licensed child care meets 55% of the potential need, according to a national analysis from the Buffett Early Childhood Institute at the University of Nebraska. The average annual cost for infant care in Onslow is $12,168, according to a presentation shared at the meeting.

“It’s just the most challenging and most expensive time when people make the least amount of income,” Rochelle said.

Gaps in child care access are being felt across the county’s education continuum and across sectors. Coastal Carolina Community College President David Heatherly said at the meeting Thursday that “the need for child care is as great as it ever was.” Mark Bulris, director of elementary education at the local school district, said schools have had to shut pre-K classrooms in recent years due to funding challenges.

“We’re kind of going the wrong way,” Bulris said.

Leaders of public agencies and private industry shared their struggles to find employees due to insufficient child care.

“When I talk to my members… they can’t find people to work,” said Laurette Leagon, president of the local chamber of commerce. “And a lot of that is tied to, number one, what they pay, and number two, the availability of child care.”

A military model on base, and in the community

Onslow is home to the Marine Corps’ largest base on the East Coast, Camp Lejeune, as well as Marine Corps Air Station New River. The military presence brings an esteemed child care model to the community that could serve as an example for raising quality and access.

The Marine Corps Child and Youth Programs, regulated by the Department of the Navy and the Department of Defense, operates eight child development centers (CDCs) on the base serving 1,452 children, according to a meeting presentation. Child care programs in the community outside the base serve 3,179 children.

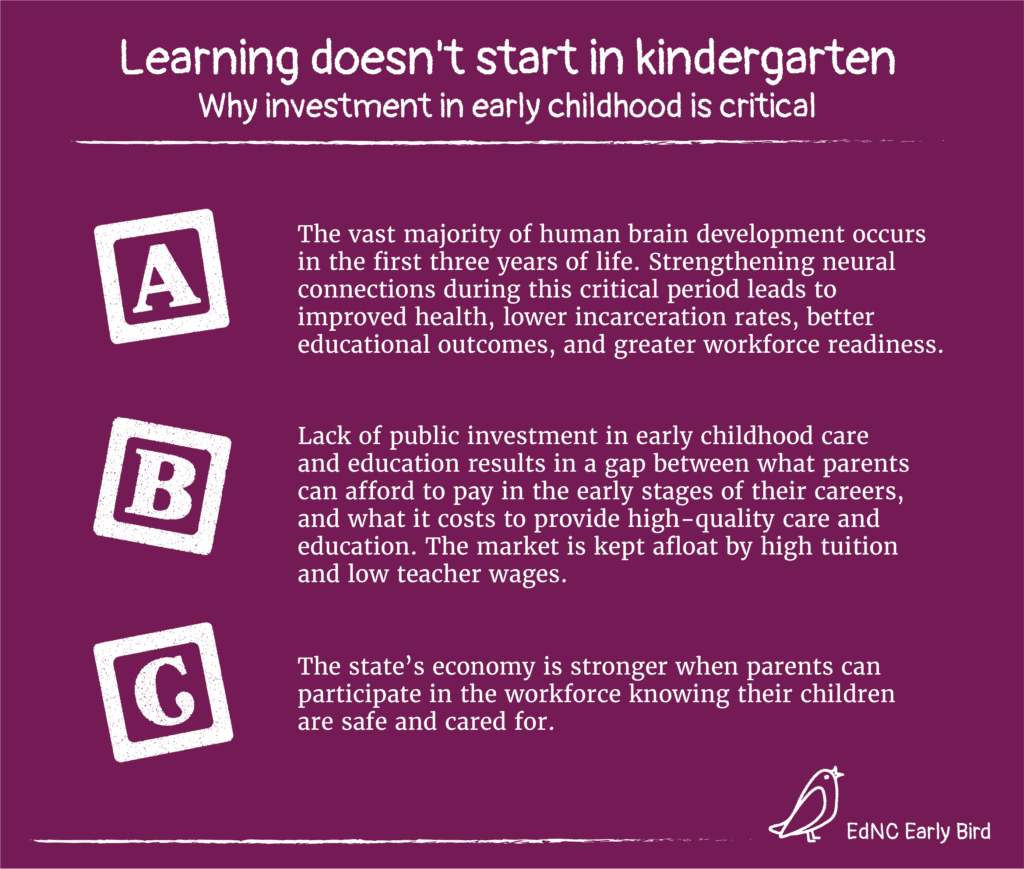

The model’s high quality and affordability for families stems from federal public investment reaching back to the Military Child Care Act of 1989. As the military population began including more parents with slim options, Congress decided to invest as a matter of national security. In 2024, DOD budgeted about $1.8 billion for child care.

“We’re a really large organization with good pay, good benefits, but we recognize the impact that has on the local community as well,” said Rachel Nelson, deputy director of marine and family programs at the bases.

That impact, task force members said, often means off-base providers cannot compete with on-based centers for teachers. Without public investment, child care programs are unable to provide competitive wages and remain affordable to parents.

Some military families still struggle with the cost of the model, which is on a sliding scale, Nelson said. And more access is needed, both on and off base.

“What we’re hearing from all our base commanders around the state of North Carolina is that child care is one of their biggest quality of life issues that they’re having, and it’s actually now currently affecting military readiness,” said Joseph Speranza, member of the NC Military Affairs Commission. “So it’s not just a local problem that’s happening. It’s actually having national implications.”

North Carolina is one of 19 states participating in the Military Child Care in Your Neighborhood-PLUS (MCCYN-PLUS) initiative, which provides stipends to help military families access high-quality child care in places with long waiting lists or when families live far from on-base options — including Onslow County.

‘It just simply does not pay’

At the root of slim access is an inability to pay early childhood teachers reasonable wages for the work of caring and educating young children. The average pay for the county’s early childhood teachers is $12.50.

Heatherly, the community college president, said he is part of statewide conversations on the viability of early childhood preparation programs because of low wages.

“It just simply does not pay at the level that really entices folks who may be very interested in the field to actually get into those various programs,” Heatherly said.

Zac Everhart, former chair of the state’s Child Care Commission and former owner of child care centers in Onslow and nearby counties, said he struggled to retain high-quality teachers before the pandemic. Since then, he said the competition has evolved and intensified.

“In your time, however long you’ve been here, what has grown on Western Boulevard?” Everhart asked fellow task force members about one of the county’s main drags. “There are more service industry jobs there every day… and they pay more.”

“It used to be we lost child care workers to other child care centers,” he said. “That’s not where they’re going now. They’re just getting out of the industry because we’re asking more of them and not paying them anymore.”

After Everhart provided industry insights, Autumn Bishop, a former teacher at one of Everhart’s centers, spoke up. Bishop, now chief early education program officer at One Place, said she is one of those many teachers who felt forced to leave the classroom due to low wages.

Related reads

Bishop said she worked two jobs, lived with coworkers, and, one summer, sold all of her furniture, to stay in the classroom.

“I worked until 2 o’clock in the morning, and then I went and drove a bus at 6:00,” Bishop said. “I’m not sure who thought that was a good idea, but that’s what I did, because I wanted to do this work, but that’s the only way I could afford to do this work.”

After Bishop had her own son, she decided she needed to create opportunity for her family. In 2015, she left.

“If the pay ever changes, I will be the first one that runs back into a classroom,” she said.

Rochelle said recruiting and retaining teachers in the field will require solutions that work for the county’s transient community. That might mean emphasizing on-the-job training for high school graduates, she said.

“How can we capitalize on the workforce that we have for the time that we have them?” she said.

The task force will host roundtable discussions from November to February to hear the experiences and input of various sectors and groups: business leaders, education stakeholders, child care providers, parents of young children, and members of the military community. The full task force will meet again on March 12, 2026, and present at One Place’s annual State of the Child event in April.

In the meantime, Rochelle asked task force members to spark conversations in their lives and workplaces about child care, and to spread the word of the task force “to help the wider community to know… that we are a caring community.”

Recommended reading