|

|

EdNC is highlighting the experiences of educators, families, researchers, and advocates with a stake in North Carolina’s early care and learning landscape. These profiles illustrate that care and education are inseparable, especially in a child’s first five years — caregivers educate, and educators care. In this series, we refer to those profiled in the way they are known by their community.

The commanding officer of U.S. Coast Guard Base Elizabeth City was surprised to find herself choking up while she shared her experience as a parent with a gathering of early childhood professionals in March 2025. She told them:

You are the stability for our children. I still remember the days dropping my kids off when my husband was deploying and [educators like you] were the ones peeling the kids off of us. They were the ones that got our kids through those deployments. It’s really personal. You don’t know how much you mean for us… We don’t have stability in our lives at all, and you are it for us. And it makes a difference.

Reflecting on that moment three months later while sitting at the conference table in her office, Commander Heidi L. Koski told EdNC she could still hear her daughters crying through the child care center’s hall when recalling that time in her family’s life.

“I just think military kids are amazing,” Commander Koski said. “And I’m a little biased, I know, but they’re pretty special people who didn’t sign up for it, but yet they’re serving anyway, and they just go with it.”

Her daughter Kennedy — “like the president” — is 13 now. Her daughter Senia is 10, and has learning differences that were identified by her preschool teachers.

Commander Koski said the reason she’s been able to serve two decades in the Coast Guard and rise to her leadership position is the support of her superior officers and the early childhood educators who cared for her girls.

Sustained, superior performance

Commander Koski grew up in Davie County, where both of her parents were educators, and her dad eventually served as superintendent of schools. She moved to Durham to attend the North Carolina School of Science and Mathematics (NCSSM) for high school.

Sitting in a traditional classroom wasn’t for her, so when it was time to think about the next step on her educational journey, she was attracted to the U.S. Coast Guard Academy. She and three of her NCSSM classmates attended together.

Serving in the Coast Guard took her to Florida, where she met her husband, another Guardsman (aka “Coastie”). They got married, were assigned to Coast Guard Headquarters in Washington, D.C., and decided to try adding children to their family.

Commander Koski said she knew that decision could affect her career, because she wouldn’t be able to go back to sea.

“Back then there was a little bit more of a stigma,” she said “I think most people just expected me to get out. They’re like, ‘You chose not to go back to sea, your career is probably going to be over, you probably won’t make [Lieutenant Commander].’”

Making that rank was a big deal for her, because it would guarantee her retirement income after 20 years of service. She told herself she’d just have to be a “really hard performer; sustained, superior performance will always get you through.”

She and her husband did fertility treatments, and she got pregnant and gave birth while they were living in Alexandria, Virginia. She had just six weeks of maternity leave.

“At six weeks I wasn’t even medically cleared from having a C-section, and I had to go back to work,” she recalled.

And she didn’t have immediate access to child care. Her family was on the waitlist for the child development center on base for more than a year.

She and her husband made it work, which sometimes meant one of them handing off their infant daughter to the other at a Metro station between shifts. She started to wonder whether she should give up her military career.

Until one day when she had their baby with her at work and was unexpectedly called upon to brief an admiral.

I took the baby, and I briefed the admiral. He didn’t bat an eye. He didn’t bat an eye! And so I learned in that moment you’ve got to know your stuff, you’ve got to be professional, you’ve got to just deal with what you’ve got. The baby played with my shoulder boards, and we just moved on. And I knew it was gonna be OK… People support me. They know you know your stuff, and that’s still valued. So I was still able to prove I had value.

She credits her senior officers with giving her the “leeway” to balance her duties as a parent with her duties as a Guardsman.

“But I did feel like I had to work significantly harder in my job to prove myself, to overcome that leeway,” Commander Koski said. “I’ve taken the hard jobs, I haven’t shied away from it, to make sure I show my worth.”

Waitlists and reassignments

Coasties are typically reassigned to a new duty station every two to four years. Any time a reassignment was coming up, Commander Koski had to research the places they might be sent, and put deposits down to get on waitlists at several child care programs in each location.

“You normally had to pay 100 bucks or so to be put on a waitlist and hope a spot, if we got [assigned to] that city, would be open in time,” she said. “You dump about $1,500 just to waitlist, and then you get where you’re actually going, and then you’re still on a waitlist.”

She said the process was not only expensive, but stressful.

“Sometimes you have to take the less-than-desirable [child care] option, and that’s nerve-wracking, because if your child’s not OK, then you’re not OK,” she said.

That experience informed her approach to her second pregnancy.

“I put my name on the waitlist before my husband knew I was pregnant with our second child,” she said. “I found out, I immediately drove straight to the daycare and put my name on the waitlist.”

Sign up for Early Bird, our newsletter on all things early childhood.

Commander Koski’s husband was assigned to a ship for most of her second pregnancy while they were based in Hampton Roads in southeast Virginia.

He made it home three weeks before the baby was born. They had a few weeks together as a family before he had to leave again — for six months.

Operating as a single mom while pregnant and caring for a toddler, then recovering from another C-section while caring for that toddler and newborn, all while continuing her military career, was such a difficult time in her life that Commander Koski says she’s mostly blocked it out.

But she remembers it was a different type of hardship for her husband. Their infant daughter didn’t recognize him when he came home.

“That’s a lot on the dads too,” she said.

Putting on her ‘mom’ and ‘commanding officer’ hats

Commander Koski’s experiences in the Coast Guard, both before and after becoming a parent, have informed her commitment to children and families.

When she was assigned to the U.S. Coast Guard Cutter Vigilant, she did “migrant interdiction,” mostly with people coming to Florida by sea from Haiti and Cuba.

“You see people just trying to have a better life, and their kids who have no choice in this matter, they’re just kids, they just want to have fun,” Commander Koski said. “And they’re scared, they’re terrified, but we were able to have a blast with them, like we taught them songs even with language barriers. And so that really pulls at your heartstrings and you’re like, ‘OK, I want to make sure that I’m giving back in some way.’”

She’s trying to do that in her role as commanding officer of the base.

“I’m charged with the care of my people and always having to make sure they have what they need, and for this entire campus of 3,000 people to know that they can come to work and do their mission,” Commander Koski said. “So in that regard, I honestly put on my ‘mom’ and ‘CO’ hat and make sure that their kids are in child care, that they’re in places where they feel that their kids are safe.”

That will get easier in the next few years. Base Elizabeth City has funding approval for a new military-operated child development center (CDC) to be built on the campus. The groundbreaking is scheduled for 2026, and Commander Koski is making crucial decisions about its design and construction.

She’s bringing her own experience as a Guardsman and a mom to the process. And she hopes the groundbreaking will happen before her next career move — retirement.

“I chose to retire,” she said. “I was actually up for promotion, and a lot comes with that. You have to be willing to go anywhere with or without your family. I said at the beginning, my family’s my priority… My husband is actually retiring at the same time. We made a pact when we decided on this lifestyle, that wherever we go, we go together.”

She wants the CDC to help other Coasties navigate their duties to their families and their careers serving their country.

“I was given a lot of leeway and ability to do both, and I want to give others that same opportunity,” Commander Koski said. “Because obviously, we’re driven to serve already by joining, and why can’t we have a family and want that? And why can’t that be our priority while we’re in the service?”

A valued service

Adding a CDC to Coast Guard Base Elizabeth City is about more than just child care; for Commander Koski it’s about preparing the next generation to lead society forward.

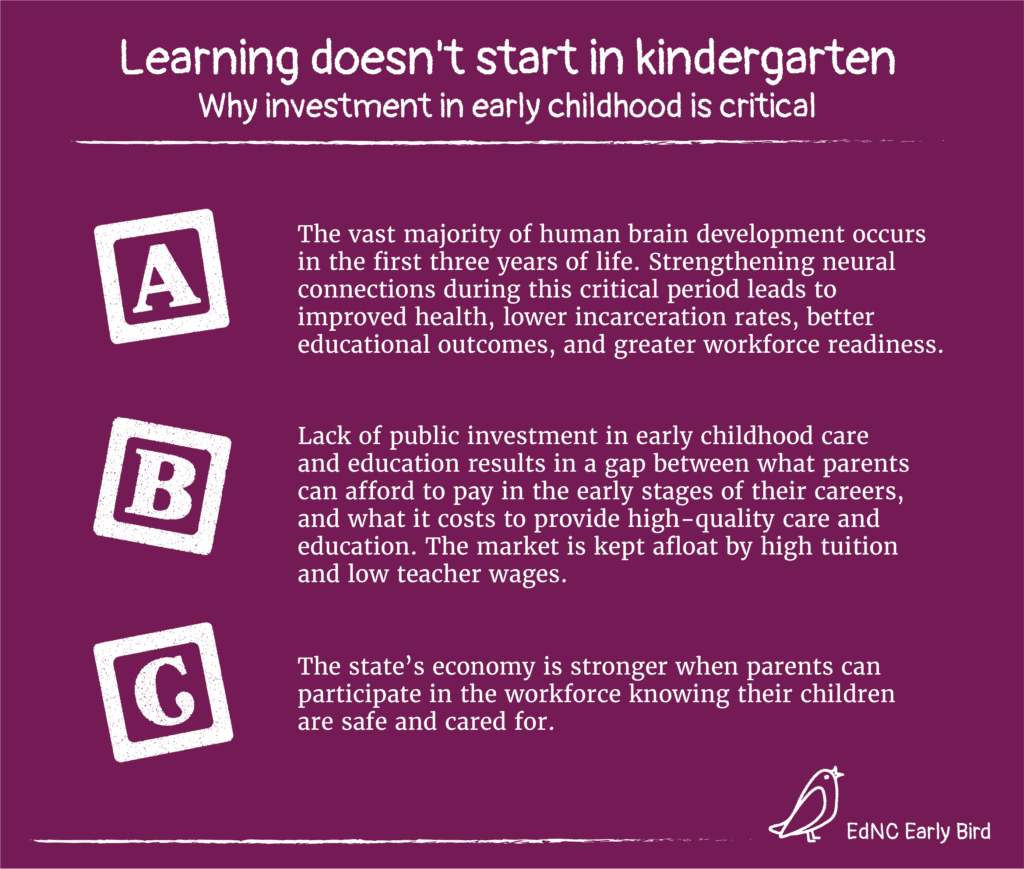

“I’m glad my kids were in that early childhood program,” she said. “I’m really grateful that they were because they learned so many social skills and norms and things that put children who don’t have that opportunity farther behind by the time they get to kindergarten.”

She makes it clear that she’s not talking about academic skills, like recognizing letters and numbers, but the skills that will help them “function in society” — sharing, patience, structure, responsibility, setting and respecting boundaries.

“I don’t think the mark of success is my child getting into Harvard; I think the mark of success is being able to contribute to society,” Commander Koski said. “And that’s what I think early childhood education and these centers can do, is to teach children how they can contribute, and how they’re part of the bigger picture.”

Commander Koski wants policymakers to think differently about how early childhood educators are compensated for the critical work they do for children and families.

“You’ve got to put as much value on the child care workers who are watching the kids as you do on me, the person who’s going to work,” she said.

When she is praised for her work or thanked for her service, she thinks of the early childhood educators who made her service possible.

In the military, we have a tradition when you get a pay raise and you make rank — you do what we call a ‘wetting-down.’ You take the difference in your paycheck, and you’re supposed to go have a party, go to bars and stuff like that. My husband and I decided to take our pay raise and give it to the child care centers… I was like, ‘I can’t do my job without you guys,’ so we thought the wetting-down was more appropriate for them… I’ve never told anyone else, nobody else knows that, but we wanted to do this because you’re supposed to share it with the ones who helped get you that rank. And we knew those were the people that got us to them.

She’s planning to invite those educators to celebrate her retirement too.

“Without them, I would not have been able to do my job,” Commander Koski said. “And so I want to make sure they know that their value to society is just as important, if not more, than my value to what we’re doing.”

Recommended reading