Plus a look at a case study released on the leadership of Carice Sanchez and Henderson Collegiate

On April 12, 1995, House Bill 955 — a bill authorizing the creation and funding of public charter schools in North Carolina — was filed.

The purpose of public charter schools includes by statute:

- improving student learning;

- increasing learning opportunities for all students, with special emphasis on expanded learning experiences for students who are identified as at risk of academic failure or academically gifted;

- encouraging the use of different and innovative teaching methods;

- creating new professional opportunities for teachers, including the opportunities to be responsible for the learning program at the school site; and

- holding charter schools accountable for meeting measurable student achievement results.

Almost 30 years to the day since that bill was filed, EdNC visited Henderson Collegiate on April 16, 2025, to learn more about this elementary, middle, and high school in Vance County that served 1,338 students in 2024-25.

This article looks at the leadership of Henderson Collegiate and the school’s commitment to continuous improvement through instructional practice.

![]() Sign up for the EdWeekly, a Friday roundup of the most important education news of the week.

Sign up for the EdWeekly, a Friday roundup of the most important education news of the week.

Get to know the Henderson Collegiate Pride

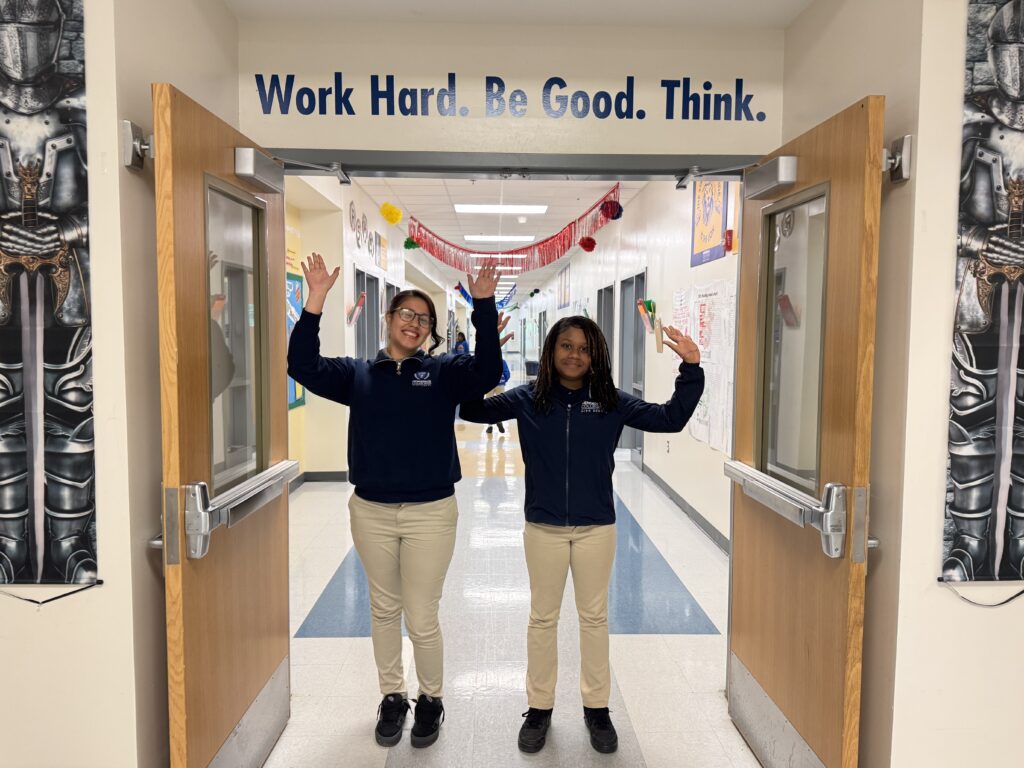

My visit started with a tour of the school led by Henderson Collegiate students Mia Joyner Martinez and Maya Williams.

The lion is the school’s mascot, and students who attend Henderson Collegiate think of themselves as part of a pride. Mia and Maya stopped me in the cafeteria where a sign explains their “values throughout the year.”

Pride | We are a team and a family that encourages and supports one another.

Responsibility | We own our learning and follow through on all commitments in order to prepare for college and for life.

Integrity | We do the right thing even when we are confronted with challenges or when no one is looking because that is what good people do.

Determination | We know that being smart is a choice, and we go above and beyond in order to build our knowledge and skills for college and life.

Enthusiasm | We have passion and show joy for learning because we learn not for school but for life.

Grades meet together daily to set expectations and celebrate achievements.

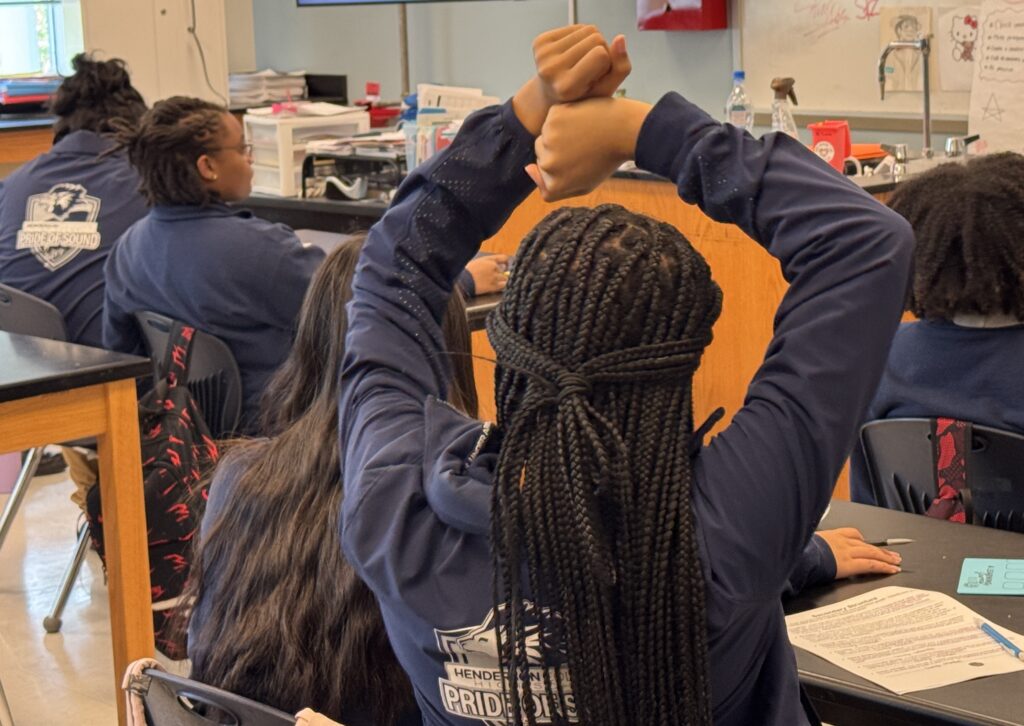

Mia and Maya explained and showed me the nonverbal communication that is used by students to communicate.

As we walked around the school, Mia and Maya pointed out all of the different ways it is clear to students what the expectations are — do the right thing — and what the mission is — go to college.

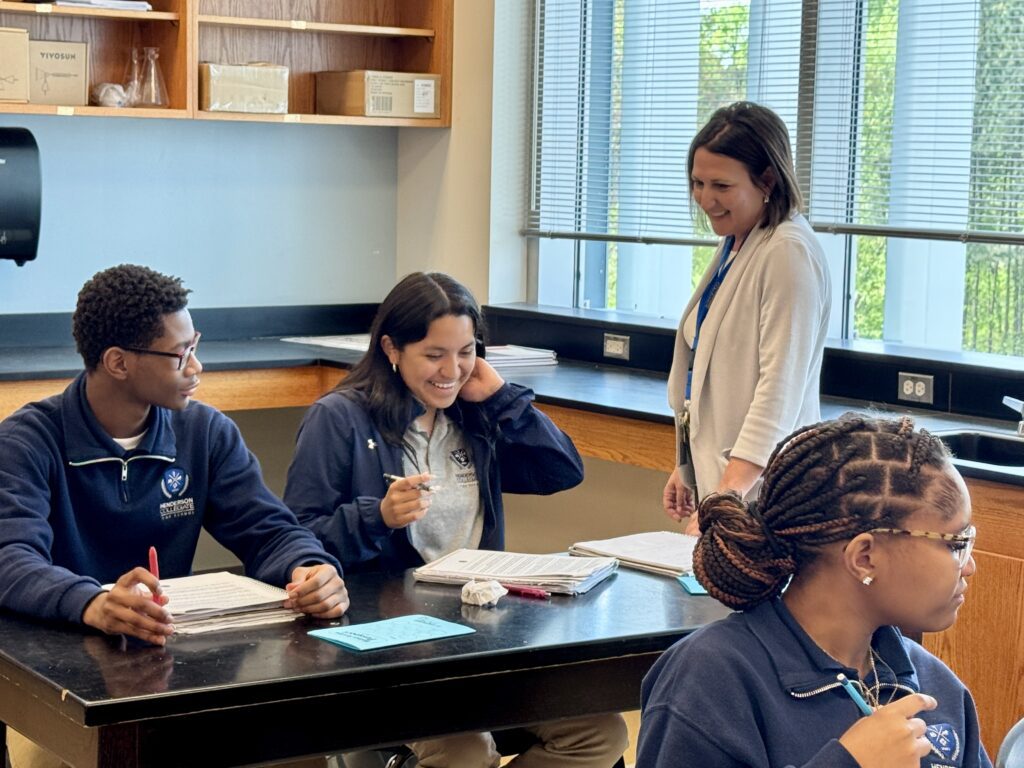

Mebane Rash/EdNC

Henderson Collegiate was established in 2010 by Eric and Carice Sanchez. The story of the school is a love story, says the website.

“In 2002, we were both sent to teach here in Vance County public schools as part of Teach for America. Not only did we meet each other, fall in love, and get married thanks to this experience, we also fell in love with the Henderson community. …

Just like it started, the story of Henderson Collegiate continues to be a love story to this day. It’s about a love for our students — also for our parents, our caregivers, our teachers, instructional coaches, and staff.

It’s a love for this community where there continues to be so much possibility for meaningful change and success.”

Since its founding, the school has exceeded growth goals every year and earned an A or B every year since the introduction of the state’s school grading system.

When U.S. News & World Report released its 2025-26 list of best high schools in North Carolina, Henderson Collegiate ranked #24 (top 3.5%).

According to the school, 86% of the students served are economically disadvantaged and 96% are students of color. Of the 154 people on staff, there is an 89% retention rate and 62% are people of color.

The achievement that is celebrated the most at this school? Each year in May, on senior signing day, students reveal their college of choice, celebrating 100% college acceptance. At the celebration, students and their loved ones pledge for the students to stay enrolled full-time at an accredited college, reach out for help when needed, and stay in touch with Henderson Collegiate.

At the celebration, the school welcomes back alumni who are recent college graduates to showcase “the full journey of our Pride.” The mission, says the school, “isn’t just to get students to college — but through college and into lives of impact.”

As the school strives to set new standards for excellence for itself, it says it is “pushing the boundaries of what is possible in education, and providing a blueprint for schools across the nation.”

Recognizing that the challenges facing students, families, and educators extend beyond the classroom, the founders of Henderson Collegiate launched “Want More? Do More!” to expand the school’s impact. Their vision was to create a platform that not only equips teachers and leaders with the tools they need to drive student success, but also shares the proven practices that have transformed outcomes in their own community. By doing so, they sought to multiply the effect of Henderson Collegiate’s model — helping more schools, more educators, and ultimately more children break cycles of poverty and realize their full potential.

“Want More? Do More!” is a for-profit company, offering both an educator preparation program to teachers who need a license and an instructional leadership cohort, which is a year-long program that supports individual leader development and school growth.

Here is an in-depth look at the leadership of Carice Sanchez, who serves as chief academic officer of Henderson Collegiate.

A ‘Platinum Leader in the Field’

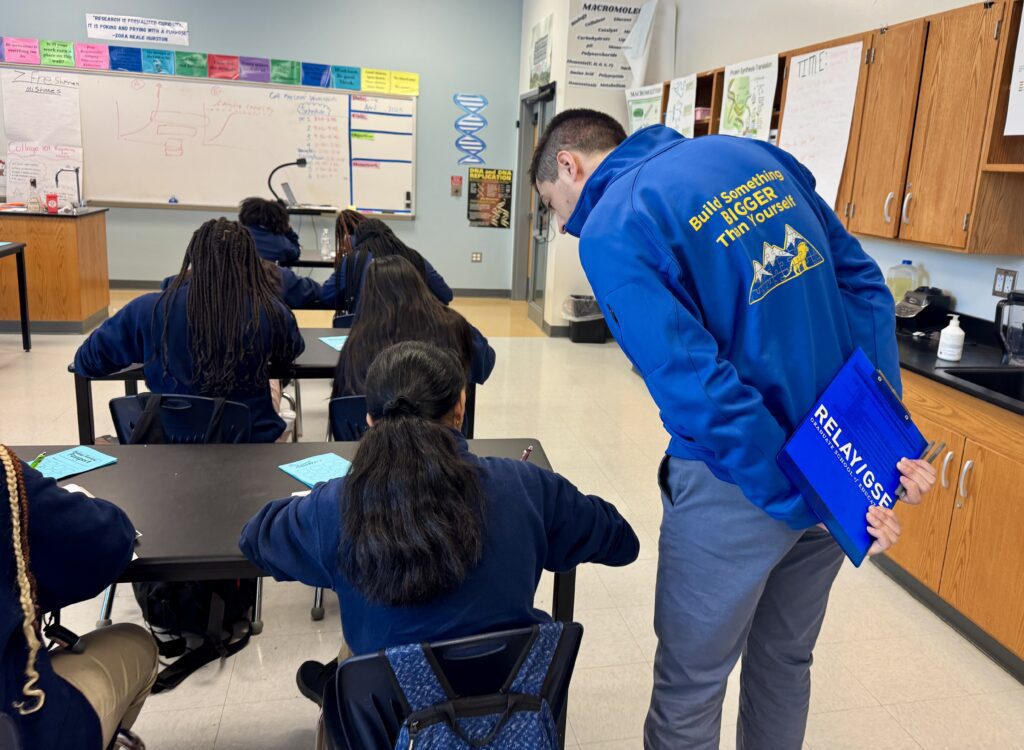

Early in 2025, education leaders from across the United States and countries including the United Kingdom, Chile, India, and Singapore visited North Carolina to observe, study, and evaluate the leadership of Carice Sanchez, including school culture, team culture, observations, data-driven instruction, and ongoing professional development.

The cohort of leaders who visited North Carolina is part of the Relay Graduate School of Education’s Leverage Leadership Institute (LLI) Fellowship, which according to the website, “is for high-performing principals and principal managers who serve in traditional school districts and charter management organizations from all over the world.”

LLI looks for leaders “who are in the top 10% of schools in their local district or state, and have led student outcomes to double-digit gains.”

Sanchez was named a “Platinum Leader in the Field.” Just eight of 200+ leaders have earned the distinction.

LLI was founded by Paul Bambrik-Santoyo, the author of “Leverage Leadership, Get Better Faster, Driven by Data,” to “highlight and scale the best instructional leadership practices in schools that are delivering real results for kids.”

When presenting the platinum award, Bambrick-Santoyo said LLI has the award so that “if someone asked if there is an exemplar school in the country where we could see the leadership levers in action, they could have a list of schools doing it really well.”

Curious, I asked Henderson Collegiate if I could see the leadership levers in action in a classroom.

How Henderson Collegiate improves instructional practice, step-by-step

The instructional coach role

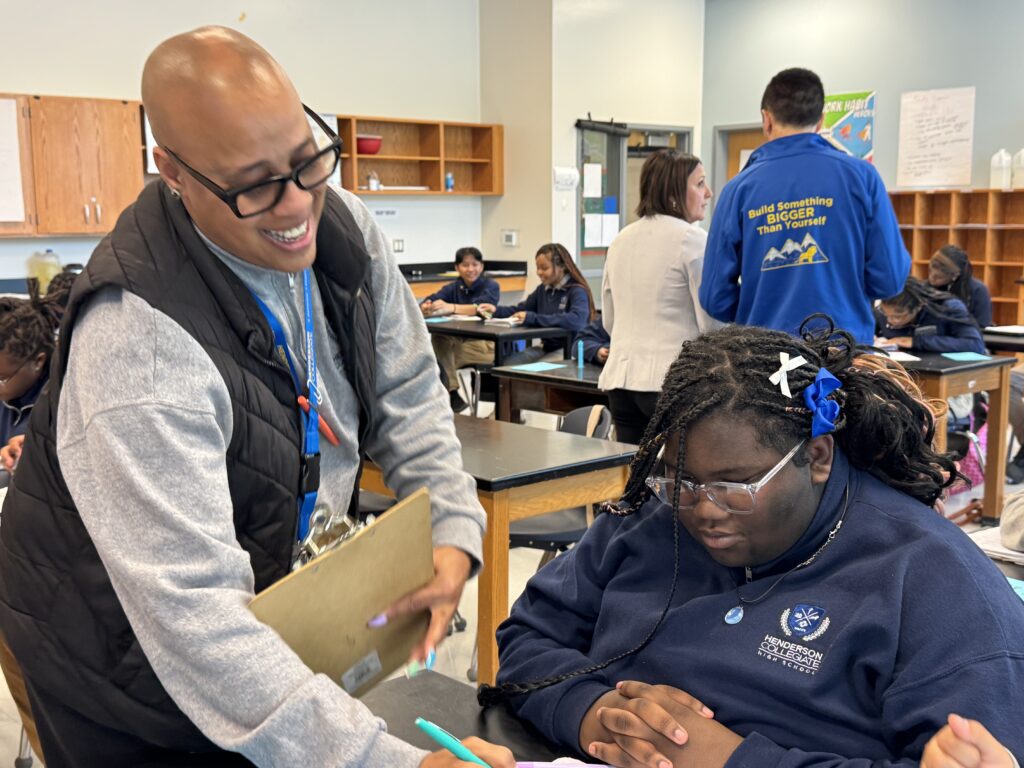

Each teacher at Henderson Collegiate has an instructional coach, who week-to-week guides their self-reflection, helps them analyze gaps in student learning, provides lesson plan feedback, observes their teaching, iterates their instructional practices, and then watches the educator practice teaching incorporating the feedback. It is in-real-time professional development.

Coaching the principal to coach the teacher and instructional coaches

Beyond instructional coaching, Sanchez works with the principals at Henderson Collegiate to analyze and address gaps in learning.

Previously this type of support was offered for “priority classes,” those not on track to meet an end-of-year goal. Feedback from LLI included the need for all coaches to be able to use student work to: 1) identify where students are encountering “the productive struggle,” 2) know what to look for when walking in the classroom, and 3) coach the teacher to close the gap.

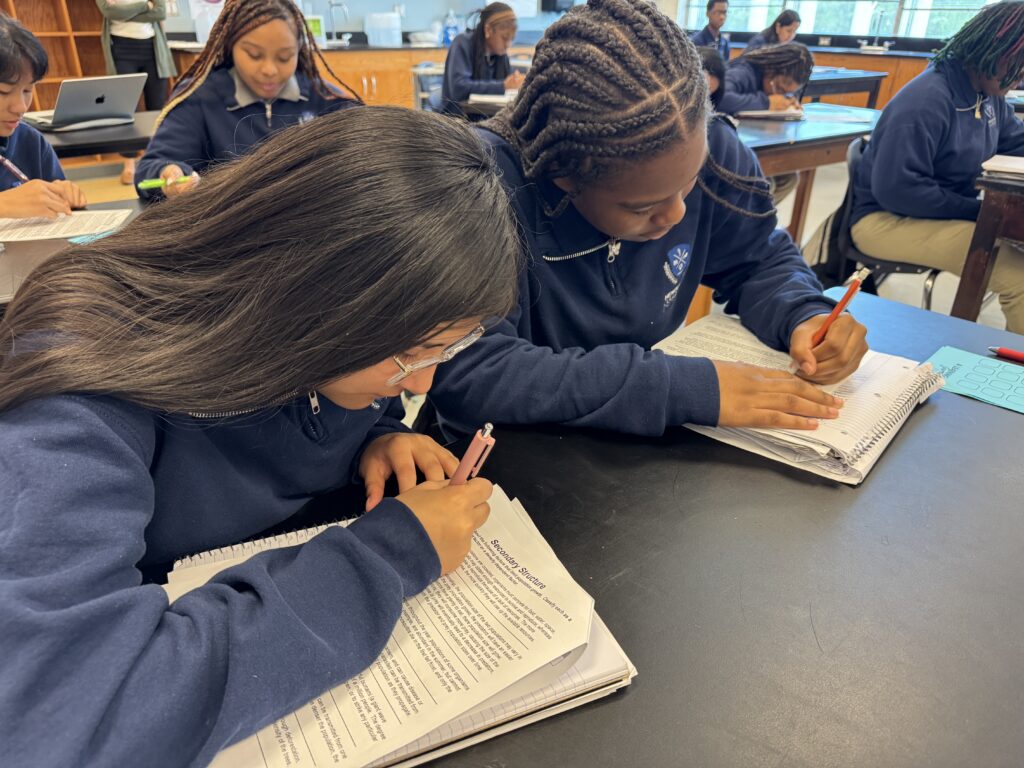

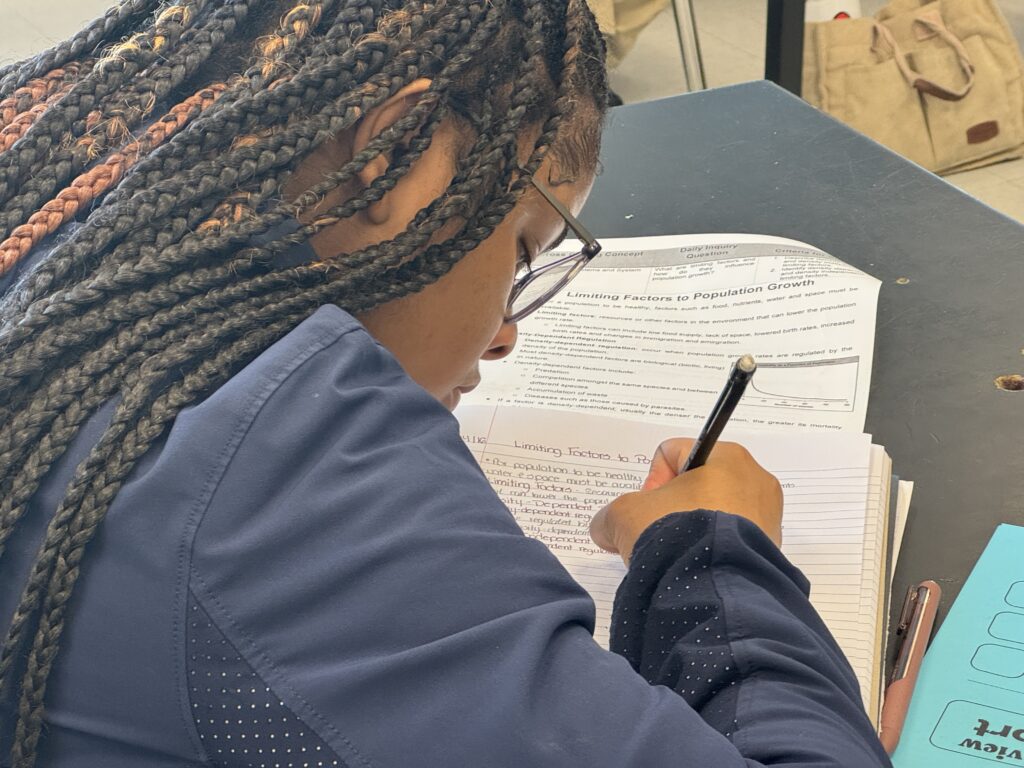

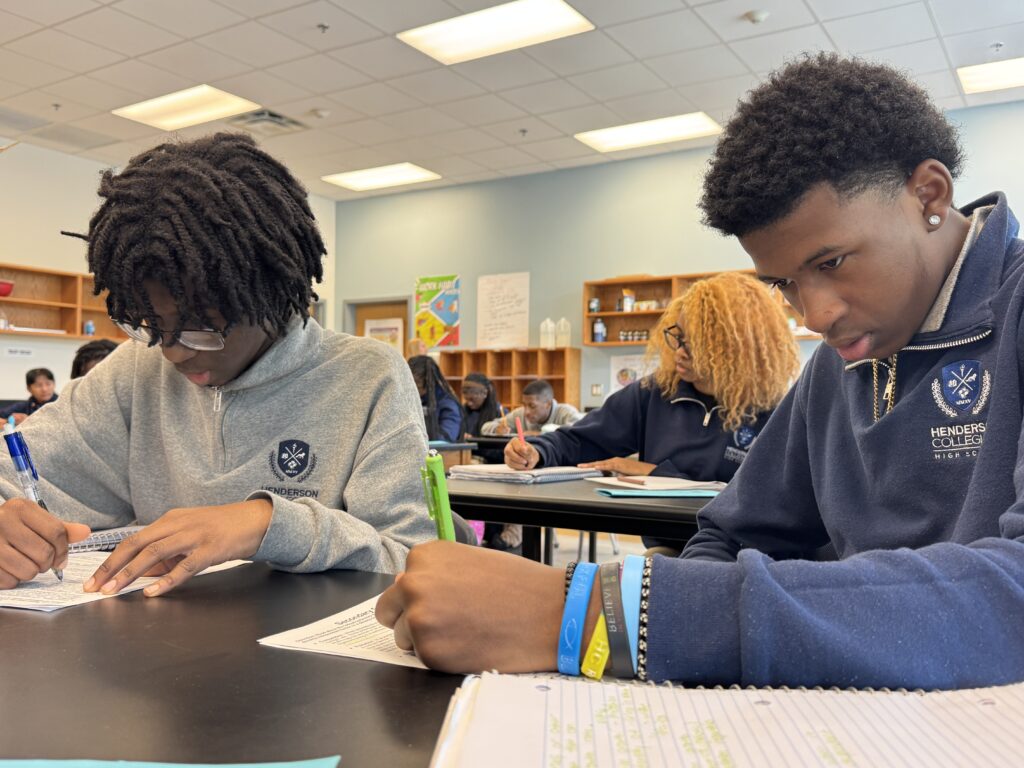

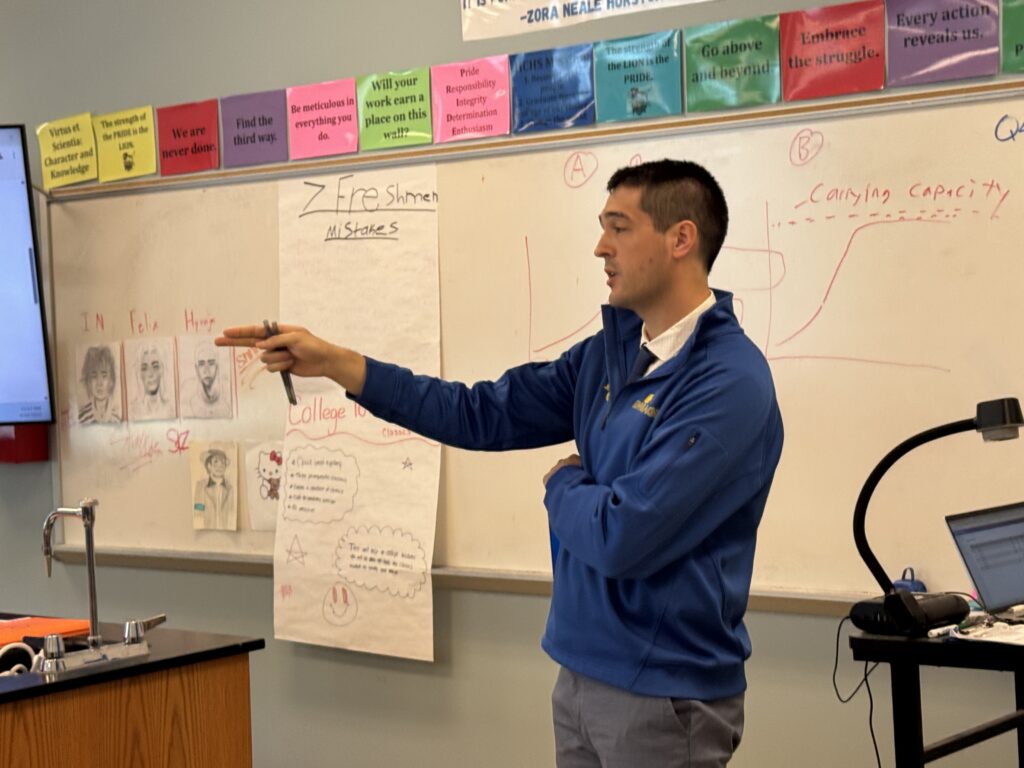

On the day EdNC visited Henderson Collegiate, I observed how this works in the class of Jaimi Semper’s ninth grade biology class. The class was learning about factors that limit population growth. Density-dependent factors include predation, competition for resources, accumulation of waste, and disease. Density-independent factors include weather, natural disasters, and pollution.

Before the coach enters the classroom

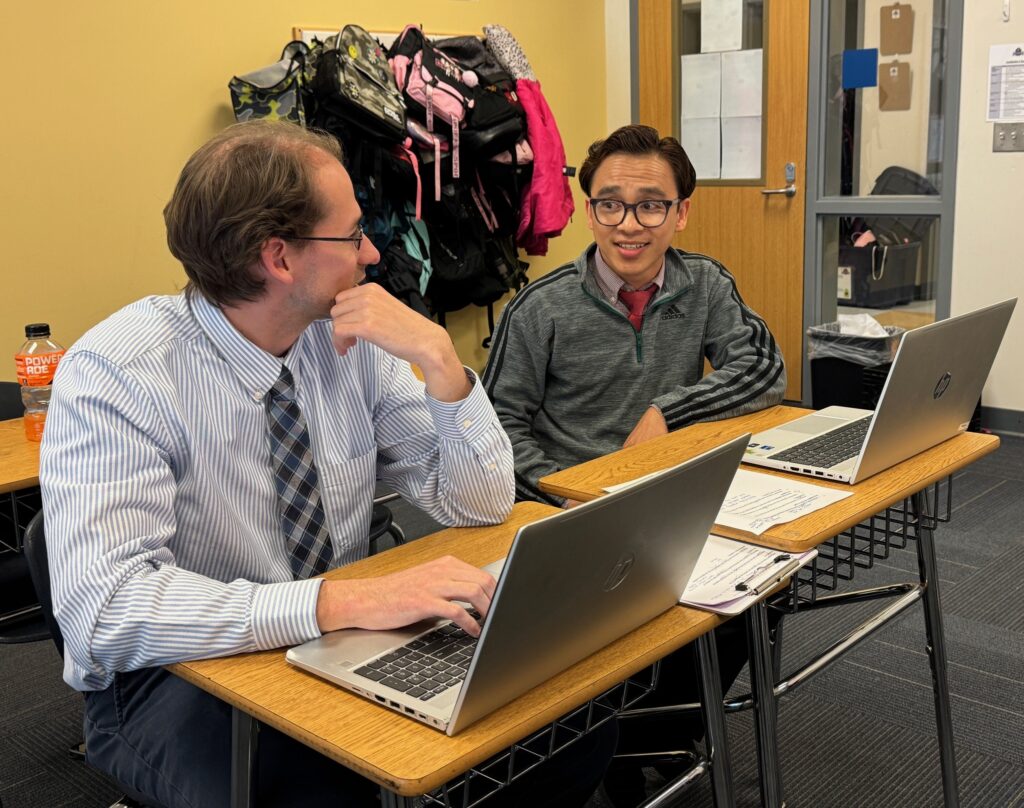

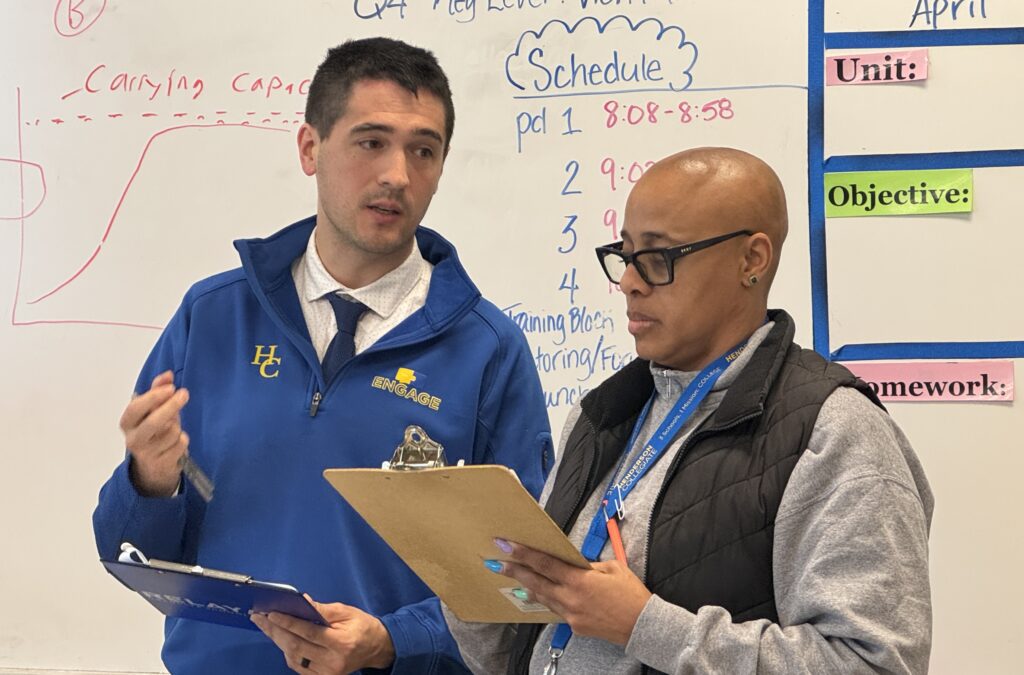

Before we went to the classroom, Sanchez met with Taro Shigenobu, the high school principal, for about 20 minutes. Sanchez prepped the principal to both coach the teacher and coach his other instructional coaches.

She explained to me that you have to enter the classroom at the time of “the productive struggle.”

Ahead of the meeting with Sanchez, Shigenobu reviewed student work and/or observed a class, identified the student gap in learning, identified the teacher gap in instruction that is leading to the student gap, and came up with suggestions about how to address these gaps.

“What is our drop in time?” Sanchez asked first. The class started at 10:50 a.m., and Shigenobu wants to be in the class at 11:10 a.m.

“Let’s jump into it,” Sanchez said. She asked Shigenobu, based on an upcoming assessment, what the most important learning objective is for students in today’s class.

“Students,” he said, “need to be able to describe density-dependent and density-independent factors and understand that both of these things limit population growth, see examples of both, identify which is which, and explain why.”

In today’s class, Sanchez asked, where should we focus our attention?

Shigenobu wanted to look at the student’s notes in the margin of the worksheet to see if they understand the difference between density-dependent and density-independent factors. He also wanted to look at the exit ticket, a short quiz the students will complete before they leave class.

Sanchez affirmed that the marginal notes are important, “because if kids do that well it will lead to mastery on the exit ticket.”

“Let’s name the gap in student work that we need to close,” said Sanchez.

After the principal named the gap, Sanchez said, “That’s the moment of the most productive struggle. Why?”

Shigenobu said it’s the moment when students might better understand the difference between what makes a factor dependent versus independent.

“What might be the teacher gap?” asked Sanchez.

She then asked the principal to walk her through real-time feedback for the teacher from least invasive to most invasive.

The principal relied first on universal prompts for the teacher: what’s most important right now, what’s the work showing, and what are you going to do to close the gap?

Since Shigenobu observed this lesson being taught to a different class earlier in the day, he also had more targeted questions, like, “What questions are you going to actually ask the students to make sure we are closing the gap?”

Sanchez then role played what might happen as the teacher is receiving feedback.

They walked through the sequencing of the questions they want the teacher to pose to students to help them understand the difference between density-dependent and density-independent factors.

When students show conceptual understanding in class, teachers are expected to “stamp” the learning — that’s an acronym that stands for STAndards-based Measurement of Proficiency. Imagine a teacher following up with, “Hey, that was a really good takeaway, write it down or tell your partner, but do something to make sure you remember it,” Shigenobu explained.

Sanchez noted that if the educator doesn’t stamp the moment the gap is closed, the principal needs to jump in and do it.

If the teacher’s strategy to close the gap in learning is not aligned with the principal’s or real-time feedback isn’t working, then the principal steps in and models how to close the gap for the teacher.

“The coaches do not leave the classroom until the student has learned the objective,” Sanchez said.

The “beautiful and” of this support happens when the student learning gap is closed because the teacher has received coaching, Sanchez said. But that doesn’t always happen, and student learning takes priority in the classroom over coaching the teacher.

“The coach’s job is to not leave the classroom until the kids have learned the lesson,” Sanchez said. The coach can then debrief after with the teacher.

“This has allowed our coaches to be masters of the content and move data when they walk into a classroom,” Sanchez said.

When coaches model for teachers, they over-exaggerate the modeling to help the teacher focus on the changes in their practice that are needed and expected.

“It’s helped us make sure student work is rigorous,” said Sanchez. “It clearly defines for us what the students and teachers are doing well and not well. And we are actually boosting student learning.”

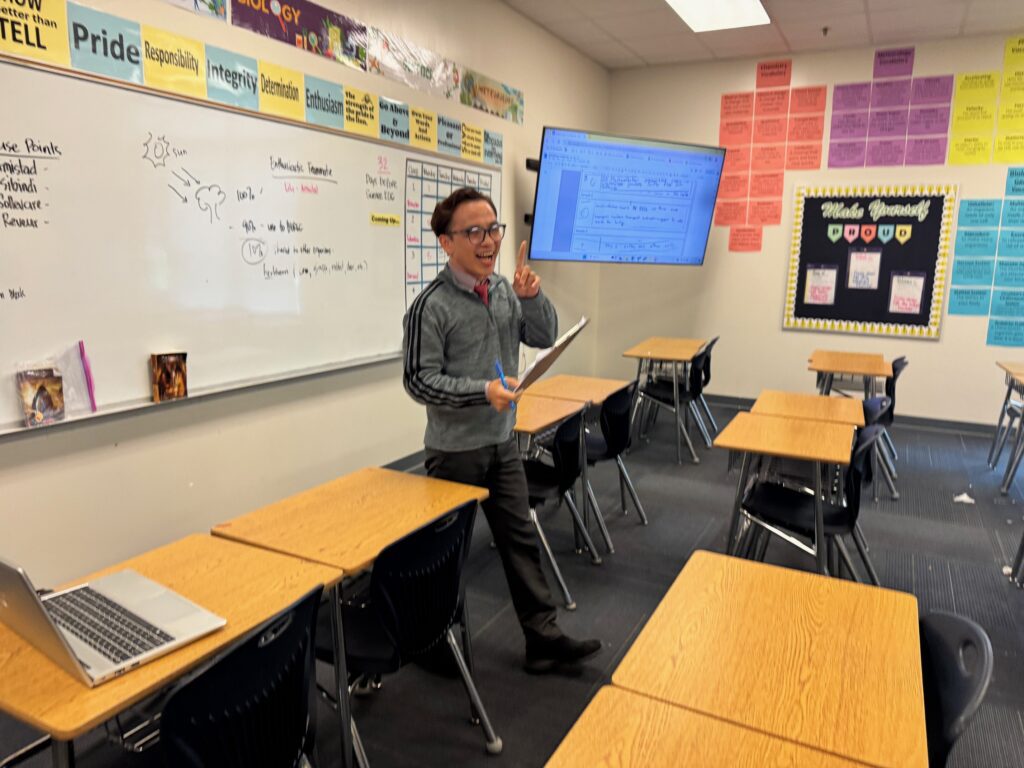

Closing a learning gap in a classroom

“When you enter a classroom, your eyes naturally want to go to the teacher. What is the teacher doing? What action step needs to be provided for the instruction to get better,” said Sanchez. “We are switching that paradigm. We go first to student work. What are the gaps in learning? In their productive struggle, what are they missing?”

As they entered the classroom, Sanchez and Shigenobu reminded each other to focus on the students and their work first.

They started out side-by-side looking at the student work to see if the gap aligns with what they thought it would be. If not, they pivot. In this case, it did, so they continued.

“This process helps us better understand the teacher gap that is leading to the student gap,” Sanchez said.

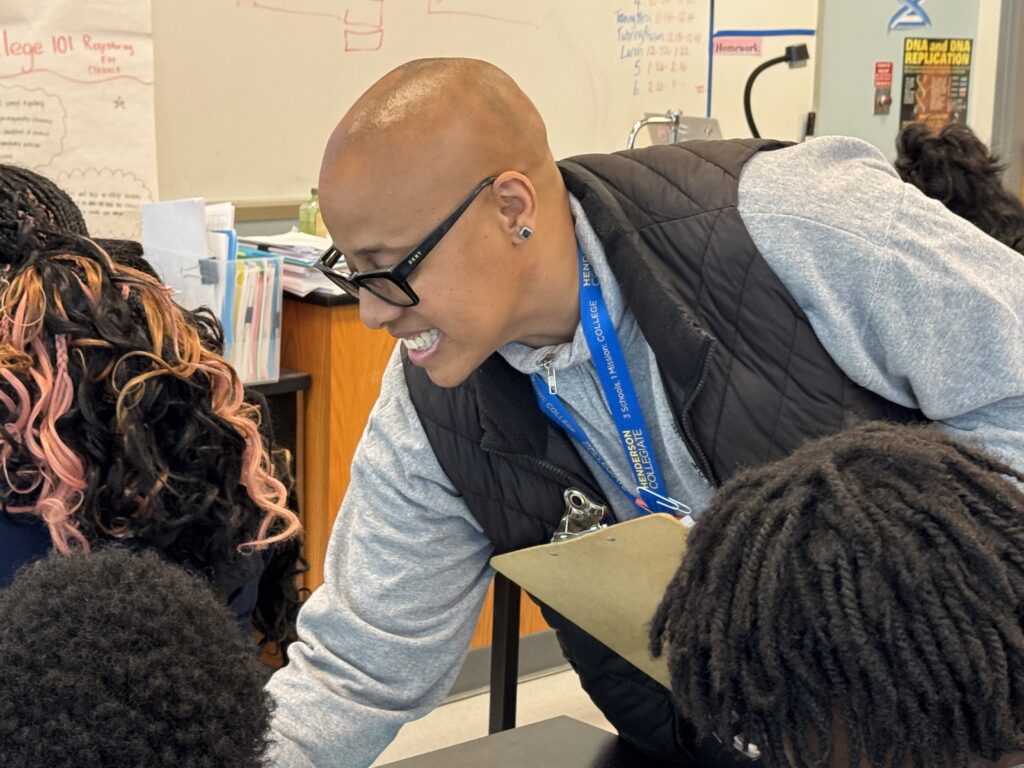

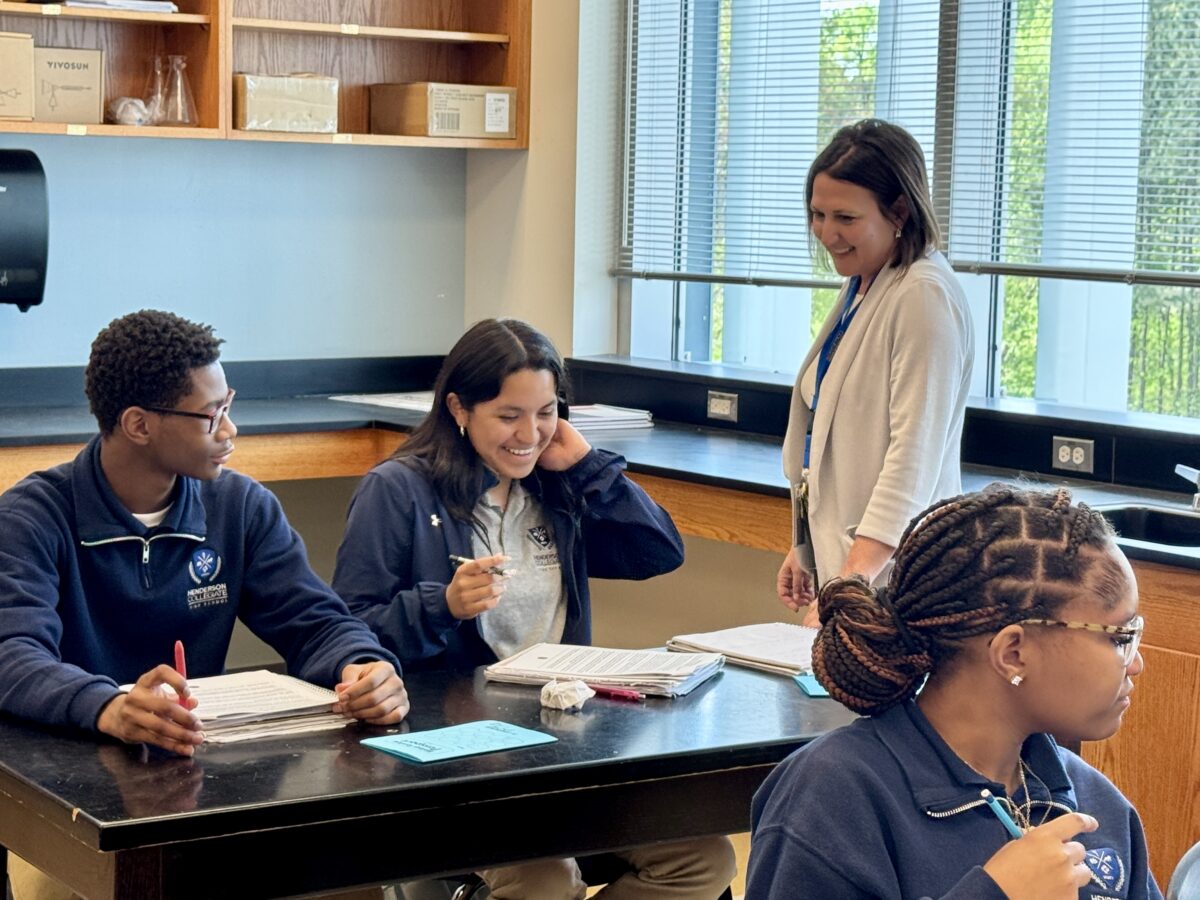

Mebane Rash/EdNC

Mebane Rash/EdNC

Even with this support and two stamps during the class highlighting conceptual understanding, one question on the exit ticket — “A harsh winter causes the Kaibab deer population to decline. What type of limiting factor is it?” — continues to be a challenge. Sanchez says having the two of them in the class got 10-12 more students over the hump.

After class, Sanchez and Shigenobu debriefed for 20 minutes, coming up with action steps for the students, the teacher, and for himself as the coach giving feedback. Sanchez noted the principal knew the lesson “like the back of his hand,” he knew the student gap, and he knew how to close it.

She affirmed the principal for jumping in quicker, which he has been working on.

She also affirmed him for identifying the annotations on the worksheet needed to address the gap on the exit ticket and the partner work between students that could provide the throughline on what needed to be fixed.

She affirmed him for working with the teacher to consistently provide stamps for students when conceptual learning is happening in the classroom.

Since a gap remained at the end of class, Sanchez provided action steps. For the seven to eight kids that didn’t get the exit ticket item correct, she expected a plan.

The next day, the teacher will start with those students.

During the debrief, Sanchez and Shigenobu discussed whether a mini re-teach is warranted or whether the principal needs to model the lesson.

“The data suck,” Shigenobu said, frustrated that it didn’t improve more from the earlier class he had observed. “There remains a gap in how students are actually understanding.”

Before he left the classroom, the principal debriefed with the teacher, and in her next class, he asked Semper to have students do more explanation of the difference out loud. He wanted to know if that strategy will close the gap.

This is a concept that will be on the end-of-course test, so Sanchez suggested putting a different version of the same question on the exit ticket the next day while the concepts are fresh for students.

Ahead of the class, the principal will coach the teacher on a re-teach strategy, and then the teacher will text both Sanchez and Shigenobu the exit ticket data the following day.

If the data doesn’t improve, Sanchez and Shigenobu will design a more robust lesson plan.

Every instructional leader at Henderson Collegiate taught at the school and became a champion teacher, Sanchez said, learning the “HC way” and the “HC DNA.”

“Resumes are great,” she said, but she is looking for instructional leaders who know how to teach well and who are “hungry, humble, and smart.”

“They need to be ready to turn intention into action,” said Sanchez, when it comes to closing the opportunity gap. “That’s what we hire for.”

A case study on ‘real time’ adjustments in teaching

Earlier this year, Relay/GSE released a case study, titled “Accelerating Student Mastery Through ‘Real Time’ Adjustments in Teaching: Learning to Apply High Impact Leadership Strategies at Henderson Collegiate.”

The case study finds the school has been able to monitor student learning in real time and make immediate instructional adjustments by:

- Making a paradigm shift in coaching — from focusing primarily on teacher actions to analyzing student learning as the basis for feedback and instructional change;

- Adapting collaborative planning to zero in on the most important student learning goals and align on how to check for and respond to evidence of mastery in the moment;

- Drawing on a coaching model with an aligned methodology, principal supervisors were able to effectively guide principals in coaching both teachers and instructional leaders; and

- Reinforcing a culture of feedback and continuous improvement by celebrating growth in the moment — at every level of the system.

From what happens in the classroom to what is documented in this case study, you can see this school striving to meet the statutory purpose of a public charter school.

The day before my visit, leaders from Tulsa, Oklahoma, visited Henderson Collegiate, wanting to learn more about this school’s blueprint.

“School leaders come from all over the country to visit Henderson Collegiate, just as we visit the best schools all over to identify and replicate best practices,” said Sanchez.

But here in the classrooms of Henderson Collegiate, the focus since its founding has been on setting higher and higher standards of excellence for itself.

This student’s reaction to a stamp — a lightbulb moment in a very hard biology lesson when the struggle did become productive — is the best evidence of why that matters.

Recommended reading