This article was published originally on April 20, 2016, the 45th anniversary of the U.S. Supreme Court’s decision in Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Education. A community conversation will be held in Charlotte on Wednesday, September 20, 2016, connecting the past, present, and future of this important case on our students and our schools, a community and our state.

THE NIGHT AFTER the Carolina Panthers lost Super Bowl 50, more than a thousand fans packed onto the sidewalks around Bank of America Stadium in Uptown Charlotte to hen perry

elcome the team home. They were black and white, poor and wealthy, successful and struggling. They stood side by side, whooping and cheering.

But at a time when Charlotte has never felt more united, the discussion in a Methodist Church some 20 miles to the South laid plain the deep divisions on race, economic opportunity, and education in a city that for decades viewed itself as a national model for successful public school integration.

The green folding chairs lined up in rows were filled, mostly, with white parents of Charlotte-Mecklenburg Schools students. CMS, as the district is called, serves roughly 145,000 students, is the second largest school system in North Carolina, and is the 17th largest district in the nation. This meeting was in Pineville, a predominantly white small town in southern Mecklenburg County – essentially an extension of the Charlotte suburbs – that’s home to conservative politics and high-performing public schools.

The audience had gathered for a community forum about the upcoming CMS student assignment review, a process the district launches every six years or so to re-draw the boundaries that determine where kids go to school. It has almost always been acrimonious, but especially so this year. Public school campuses have resegregated by race and by income since the end of court support for the plans that integrated the districts schools. Without a judge telling CMS that the district must use student assignment to balance racial or other demographics, the school board has broad authority to draw the boundaries as it sees fit.

The Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Education and groups like the one that hosted this meeting have suggested using student assignment as a tool to address economic isolation in the county’s schools. A vocal and politically influential group of parents from the suburbs disagrees, viewing the suggestion as a call to return to the court-ordered busing plan that sent children miles away from home to integrate classrooms in other parts of Charlotte.

And so – four and a half decades after the landmark Supreme Court ruling that established busing programs here and in hundreds of other school districts in the segregated South – North Carolina is once again home to a robust debate about race, poverty, and the quality of public education its students receive. It’s a discussion that’s happening elsewhere as America’s schools become increasingly segregated, but no other city has had Charlotte’s experience.

Student assignment is a contentious process. It raises concerns about the disruption of carpools and family routines. It took just under 40 minutes before a parent in the church classroom used the word fear.

MUCH OF THE NATION first learned about the Charlotte-Mecklenburg School system in September 1957, when Dorothy Counts, a black high school student, attempted to enroll at all-white Harding High. Counts, wearing a plaid dress with a ribbon down the front, was met by an angry crowd that jeered as she walked toward the school building.

Charlotte Observer photographer Don Sturkey’s picture of the scene appeared in newspapers across the country.

Dorothy Counts-Scoggins stands in front of the school building where she attempted to enroll in 1957. At the time it was all-white Harding High School, and she was its first black student. Counts-Scoggins still lives in Charlotte, and regularly attends school board meetings. The building is now the site of Irwin Academic Center. (Photo Credit: Travis Dove)

Of course, his was not the first photo of black schoolchildren braving a mob on the way to class.

Three years earlier, in 1954, a unanimous Supreme Court ruled in Brown v. Board of Education that state-sanctioned public school segregation, through so-called “separate but equal” policies established in 1896 under Plessy v. Ferguson, was unconstitutional.

The Brown ruling set into motion change at public schools throughout the nation – though some districts embraced desegregation more quickly than others. The Supreme Court said “separate educational facilities are inherently unequal,” but didn’t give guidance on how communities should go about integrating their schools. In a case the next year, the justices wrote that public school desegregation should happen “with all deliberate speed,” leaving school districts and local authority’s in charge for how and when to bring black students into white schools.

Despite that order, Charlotte struggled with desegregation even after Dorothy Counts’s attempt to desegregate Harding. The city still had 88 segregated campuses by 1965. Many were situated close to one another in what were known as dual school zones that were de facto black and white school districts throughout the city.

That year, when Rev. Darius Swann and his wife Vera wanted to enroll their son, James, in an integrated school, they were told to go to an all-black school in an adjacent neighborhood. Believing the school board’s policy to be discriminatory, they filed a lawsuit through Charlotte civil rights attorney Julius Chambers that would become Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Education, the definitive court case on pupil assignment.

In 1969 federal judge James McMillan ordered the Charlotte-Mecklenburg school board to come up with a plan to end segregated schools – a plan which McMillan rejected as insufficient. He appointed an expert from Rhode Island to devise a better, albeit complicated, strategy, which became known as the Finger Plan. It bused students of different races from neighborhood to neighborhood in an effort to fully integrate Charlotte’s schools.

In 1971, as the Finger Plan was already beginning to take hold, a unanimous Supreme Court endorsed McMillan’s ruling that busing was an acceptable strategy to use in a student assignment plan.

It’s a system that many in Charlotte believed was a success, and CMS was a model for the nation for nearly three decades, until the late 1990s when a suburban father sued the school district alleging his daughter was denied entrance into a CMS magnet school because she was white.

The court fight, which brought long-simmering suburban opposition to busing to the surface, once again divided Mecklenburg County. In 1999, federal judge Robert Potter – who had publicly opposed desegregation as a private citizen in the 1960s and 1970s – ruled that CMS was “unitary” and could no longer use race in student assignment decisions. The district appealed, but ultimately, the Fourth Circuit Court of Appeals sided with the parents.

That decision meant the school board had to adopt a new attendance boundary map – the “choice plan,” as it became known – which would move students back to the campuses closest to their homes, with options to attend magnet schools in other parts of town if parents wanted.

Fannie Flono, then a columnist for The Charlotte Observer who frequently wrote about the topics of education, race and equality, issued a grim prediction on the paper’s editorial page in the weeks after the court ruling. “Neighborhood schools,” she wrote, “will inevitably bring re-segregated schools to many sections of Charlotte. For poor black communities, that will mean concentrated poverty schools. So far, no city with such re-segregation has been able to make such schools flourish.”

THE COMMUNITY FORUM in Pineville got off to a bumpy start.

People were still trickling in as Amy Hawn Nelson, a UNC-Charlotte researcher who speaks frequently on the resegregation of Mecklenburg schools and housing, struggled to get her slide presentation to appear on a projector screen. The crowd quickly filled the room; organizers brought in extra chairs from down the hall. Some of the parents in the audience shifted in their seats. The vinyl squeaked under their blue jeans.

Finally, with the slideshow working, Hawn Nelson launched into her presentation, a variation of one she’s given dozens of times at community forums across Mecklenburg County since the school board first broached the idea of a significant student assignment review a year ago.

She called integration in Charlotte-Mecklenburg Schools “a rejected success.” Today, a third of the district’s 168 campuses are segregated by poverty. Half are segregated by race, and a fifth are hyper-segregated by race, which Hawn Nelson defines as a student body of at least 90 percent from a particular race. “We have totally re-segregated our schools,” she said.

The situation is exacerbated by Mecklenburg County’s housing patterns, which create a wedge of primarily white, affluent families in the southern part of the county and a crescent of diverse, less affluent families who wrap the urban core. “School policy is housing policy in our community and housing policy is school policy,” Hawn Nelson said.

That isolation creates profound impacts on students in CMS classrooms. Using data from the North Carolina Department of Public Instruction, Hawn Nelson selected 30 elementary schools – the 10 with the highest concentration of white students, the 10 most racially balanced and the 10 with the highest concentration of black students – and compared third grade reading proficiency scores.

In the schools with the greatest percentage of white students, 82 percent of third graders read at or above grade level. Proficiency drops to 59 percent at the balanced campuses, and to just under 29 percent at the ones with the highest concentration of black students.

The data, Hawn Nelson said, speaks for itself. “Segregation results in concentrated educational disadvantages,” she said. Diverse schools, however, yield tremendous benefits, both educational and non-academic, to children –especially to children of color and those living in poverty.

She cited roughly two-dozen studies that point to improved educational outcomes such as better test scores, higher graduation rates, and lower dropout rates for minority and poor students who attend integrated campuses. Middle-class students, she says, don’t experience academic harm by attending integrated schools, contrary to what some parents might think.

This meeting was hosted by a grassroots group called OneMECK. Its members support breaking up high concentrations of poverty in Charlotte-Mecklenburg Schools. “We don’t have a specific plan,” said Carol Sawyer, one of the group’s board members. But, generally, she explained, OneMECK believes there is an urgent need to fix the economic and racial imbalances Hawn Nelson described. “We are failing those children by assigning them to schools where educational opportunities don’t exist. We really don’t want to draw boundaries to exclude and that’s what we’ve done.”

But the notion troubles suburban parents, including several at the forum, who believe their schools are succeeding, are plenty diverse just as they are, and would be disrupted by efforts to break up clusters of poverty elsewhere in the school district. They asked pointed questions and criticized OneMECK’s approach.

“Our main concern here is our children will be targeted to help other schools,” a mom said from the middle of the room.

“Can we just say, ‘Leave us out of it?’” another asked.

One of the most outspoken fathers, a man named Andrew Snyder, punctuated the 90-minute meeting as it wrapped up. “I’ve got three kids,” he said. “I don’t want to screw them up in the next six-year experiment.”

USING THE WORD experiment to describe busing is a reflection of the historical context to student assignment in Charlotte – something recent transplants to this city don’t always understand.

In 1984, President Ronald Reagan, in town for a re-election campaign stop, departed from his typical stump speech to take a swipe at Democrats that he thought would play well in the South. “They favor busing that takes innocent children out of the neighborhood school and makes them pawns in a social experiment that nobody wants,” the president said. “And we’ve found that it failed.”

The line fell flat. News reports and recollections from the rally note the crowd’s silence in response to the president’s comment. A Charlotte Observer editorial the following morning bore the headline, “You Were Wrong, Mr. President.”

“Charlotte-Mecklenburg’s proudest achievement of the past 20 years is not the city’s impressive new skyline or its strong, growing economy,” the editorial board wrote. “Its proudest achievement is its fully integrated schools.” Newspapers throughout the southeast, and even The Washington Post, republished the searing critique of Mr. Reagan’s speech and the defense of the CMS student assignment plan that the editorial said “was shaped by caring citizens who refused to see their schools and their community torn apart by racial conflict.”

Jay Robinson, who served a decade as the CMS superintendent and was the district’s top educator at the time of Mr. Reagan’s visit, later told The New York Times, “What happened in Charlotte became a matter of community pride.”

But by the time CMS went back to court in the 1990s, many school districts across the South were moving away from busing as a tool to integrate their classrooms, viewing busing, as President Reagan did, as something to be shunned rather than embraced. Some believed they were unitary, that they had eliminated the dual system of black and white schools created during the height of segregation.

CMS fought that notion. Arthur Griffin, then the school board chairman, said the district’s legal strategy hinged on the idea that that dual system existed – at least in part, perhaps under the surface – in Charlotte-Mecklenburg, even three decades after the Swann case. “I am a native Charlottean, I went to all-black schools right here in this school district, and the same conditions that I experienced in my old high school when I graduated in 1966 are very similar to those in an all-black school today,” he said at a press conference on the afternoon of the court ruling that put an end to court-ordered busing. “We need a little bit more time to fix it.”

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

THE SIGNS did much of the talking, at least at first.

White poster board. Block letters written in black permanent marker.

KEEP NEIGHBORHOOD SCHOOLS.

EDUCATION NOT TRANSPORTATION.

NO FORCED BUSING.

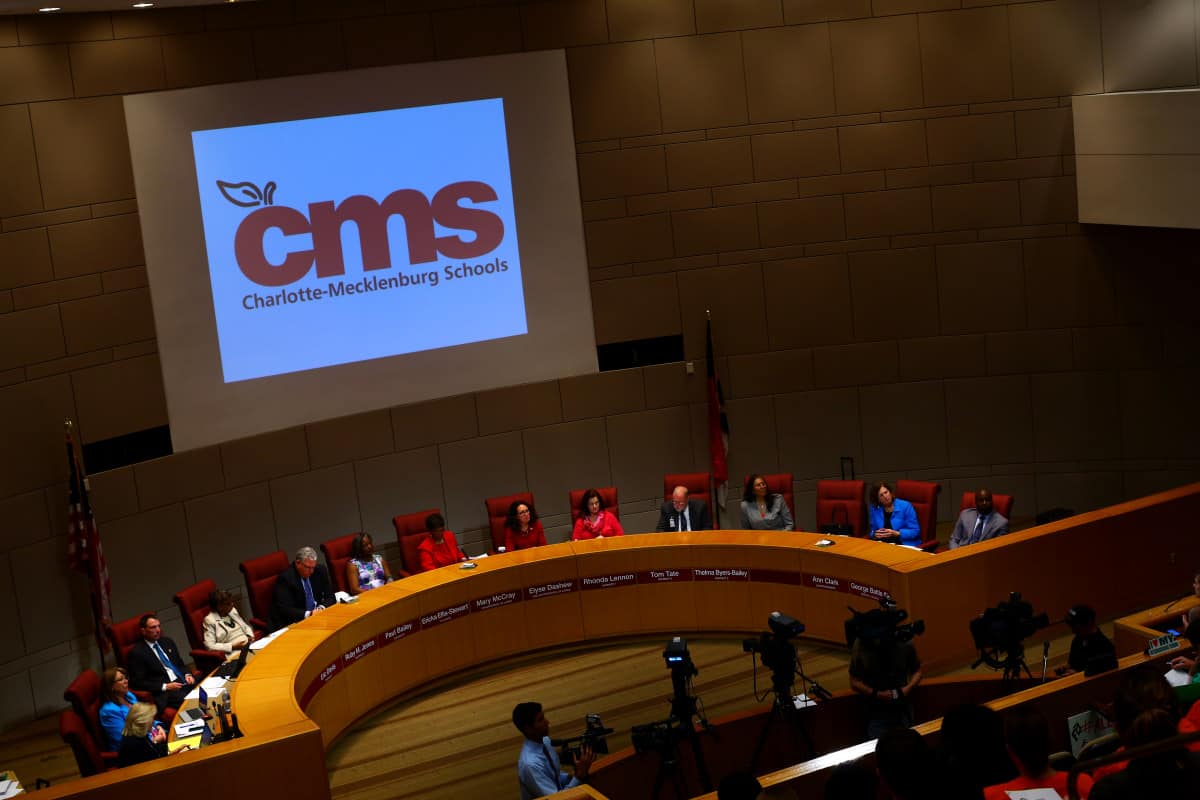

There were dozens of them, held by parents crammed into the beige meeting chamber at the Charlotte-Mecklenburg Government Center, filling all of the red seats in the auditorium that looks down on the school board dais below.

The board was holding a public hearing – just one night after the forum in Pineville – about the proposed goals for the student assignment review.

One speaker threatened to pull her kids out of CMS and enroll them in a charter school or move to an adjacent county if they are assigned to a different school.

Snyder, the father from the night before, the one who called student assignment an experiment, raised a familiar argument: increased parental involvement makes some schools stronger than others. His children attend Ballantyne Elementary and Community House Middle – two South Charlotte schools where parents routinely volunteer on campus and show up to eat lunch with their kids. “Through our efforts,” he told the school board, “we have earned the right to continue to send our children there.”

“I understand there are disadvantaged children in our community, and I am willing to do my part to help them,” he continued. “But when my child would be forced to travel to a community that does not value education to the same extent as I do, I have to draw the line.”

There were loud groans and boos from OneMECK supporters and others who support the assignment goals.

Later, Kayla Romero, who works with CMS students as North Carolina program coordinator for Students for Education Reform (SFER), a national organization that develops college students into grassroots organizers who fight for educational justice in their communities, admonished affluent parents. “Consider the privilege and advantage it takes to choose your neighborhood,” she said, drawing cheers from her supporters.

One woman, a white suburban mother, came to the podium and began to recount the experience she had as a CMS student who was bused in the late 1980s. “It was deemed a complete economic and social failure,” she said, describing how she felt bullied and isolated by attending a majority-black school.

This went on, the ping-ponging between neighborhood school advocates and supporters of the board’s assignment goals, for more than 90 minutes, as a split audience reacted to each speaker. Along the way, in an effort to move through the agenda faster, School Board Chair Mary McCray told the crowd to use “jazz hands” to show their support for a person’s comments. The cheers and jeers continued.

WHEN Jeremy Stephenson ran for an at-large school board seat last fall, he tried to drum up support from suburban voters by talking about the looming student assignment review. But the issue never really caught on and Stephenson, in his first run for office, fell about 4,000 votes short. “For whatever reason, people are engaged now,” he said. “Now you have a thousand people showing up to a meeting.”

Stephenson, who is white, works as an employment attorney and competes in triathlons for fun. Affable and opinionated, he has emerged as a leading spokesman for the neighborhood schools advocates. He dismissed Hawn Nelson’s research as “a selective blend of national studies and very small local studies,” and believes groups like OneMECK have yet to truly define what, specifically, they propose.

He bristled at the notion that suburban parents are racist because they prefer neighborhood schools. “That is horseshit,” Stephenson said in characteristic bluntness. He said people just aren’t acknowledging the diversity that exists in Charlotte’s suburbs, where people buy their homes to be close to specific schools. “You are not going to get kids out of South Charlotte involuntarily. It won’t happen.”

But Stephenson is also one of the more nuanced voices in this conversation: He readily admitted that talk of a return to 1980s-era busing is overblown. “It would be a truly nuclear option that would drive people away quickly,” he said. “I feel very confident there is zero potential that we are going to return to Swann-style busing and have encouraged folks who insist on that rhetoric to tone it down.”

Nonetheless, he said there is real concern among suburban parents who worry that their successful schools will be negatively affected by massive student assignment changes – or that their children will be bused to under-performing schools in the urban core. “We can’t make public policy on a This American Life episode,” Stephenson said. He added that the difference between his camp and those who support breaking up concentrations of poverty, “is I’m talking about what’s best for my child here, and they’re talking about what’s best for those parents over there.”

“That, to me, is parochial. It’s ‘I know better than you what’s best for you. I know for those West-side parents what’s best for their kids.’ That contains a pernicious judgment and not in a good way.”

OneMECK supporters see it differently.

They believe it is essential to represent parents who may not be able to do so themselves. “When I speak as a parent, I speak not just for my child, but all children who would be harmed by isolation,” said Justin Perry, a native Charlottean and licensed therapist who co-chairs the community group.

Perry, who is black, grew up attending integrated schools in Charlotte. In the late 1990s, when the courts were deciding whether to release CMS from its desegregation order, Perry and his friends from West Charlotte High held signs outside the courthouse. “We had a good feeling that it would potentially lead to the type of segregation that we’ve fallen into,” he said. When Perry, whose children will eventually attend Walter G. Byers School – one of Charlotte’s most isolated by race and family income – heard about the conditions a social worker saw at a local elementary school, he felt called to be part of the conversation.

“We’re setting barriers up for people who already have a lot of barriers in front of them,” he said. “But I don’t look at this as I’m asking wealthy folks to sacrifice for poor folks. I look at this as we all benefit from greater balance. Isolation in any form harms all kids.”

What both sides seem to agree on is the need for more community engagement. Stephenson said comments from people whose children attend high poverty schools – not from proxies but from those parents themselves – have been largely missing from the debate.

“Until it’s those parents saying it for themselves,” Stephenson said, “it’s you saying what you think is best for them.”

IT IS DIFFICULT to put Charlotte-Mecklenburg’s situation in a statewide – or even national – context because of the dizzying swing the district has seen in the diversity of its public schools. Hawn Nelson’s research indicates Charlotte-Mecklenburg schools are more segregated today than at any point after Swann. “What makes Charlotte so interesting is that we’ve come so far so fast,” Hawn Nelson said. “I mean, just 15 years ago our schools were diverse.”

Just before the end of court-ordered desegregation, during the 2001-02 school year, 10 Charlotte-Mecklenburg schools were isolated by race or poverty – or both, according to a UNC Charlotte analysis of data from the state Department of Public Instruction. By the 2013-14 school year, the number of racially or economically isolated campuses had quintupled, to more than 50.

“Everyone knew this would happen,” Hawn Nelson said. “That’s the frustrating thing is that we knew what would happen if we did this and we did it anyway.”

Other school systems across North Carolina and the nation have seen a similar trend, though it is magnified in large, urban districts with smaller white populations and greater disparities in family income. Asheville, Durham, Greensboro, and Wilmington – some of the state’s largest cities – have seen a trend toward resegregation, but not to the scale that Charlotte-Mecklenburg has.

“Charlotte really is just a dramatic case of increasing racial segregation since 2002,” said Helen Ladd, a Duke public policy professor who has studied changes in school demographics in North Carolina for two decades. “I’m always amazed when I look at the change in Charlotte.”

Across the state, Ladd’s research showed racial segregation in public schools leveled off by about 2008, while socioeconomic imbalances continue to increase. But Charlotte-Mecklenburg bucked the statewide trend, as the isolation of white and black students – as well as rich and poor ones – surged.

Academics tend to draw comparisons between CMS and the Wake County Public School System, the state’s largest district that serves the capital city of Raleigh. WCPSS is larger – in terms of number of students and how many ride school buses every day, as well as sheer geographic footprint – than CMS, but Raleigh buses its students fewer miles on average than Charlotte. This is because some children in CMS travel a very far and some a very short distance. “Wake’s traditional public schools are still much more racially balanced than the traditional public schools in Mecklenburg County,” Ladd says.

From 2000 to 2010, Wake County’s school board factored income level into that district’s student assignment plan. No school could have more than 40 percent of its students receiving free- or reduced-price meals. But the plan led to mixed academic results, a bitter court fight, and a new school board that promised to return to neighborhood schools.

Indeed, advocates for school choice models who often dismiss busing as a social experiment, say the comparison between Wake and Mecklenburg counties is instructive. “During the period that Wake County was doing this, Charlotte-Mecklenburg actually surpassed them in terms of student achievement,” said Terry Stoops, the director of education studies at the John Locke Foundation, a conservative think tank in Raleigh. “Charlotte-Mecklenburg’s choice model was actually producing higher student outcomes than Wake County’s socioeconomic busing model.”

Stoops said there could be other reasons for a student assignment plan like Wake County’s, like increasing upward mobility, for instance, but those reasons tend to focus on non-academic outcomes. “As a nation, we began assigning public schools all kinds of responsibilities hoping public schools could solve all kinds of social problems. It certainly begs the question of whether school is the appropriate place to do that, or whether its primary purpose, which is education, is what we need to allow the schools to focus on first and foremost and only.”

He argues that a choice plan – an option that allows parents in segregated schools to pick another alternative, either in CMS or at a charter school or private school – is a better alternative to busing. “To me to give the opportunity for kids to move to schools outside of where they live seems to be an approach that probably won’t be considered by the school board but probably should.”

The surge in charter schools in North Carolina, spurred by the Republican-led legislature’s removal of a 100-school cap in 2011, has given parents more options, but many options are also isolated by race and income. A report to the State Board of Education this year showed 57 percent of North Carolina charter school students are white, compared to just under 50 percent of traditional public school students.

“It looks to us as if charter schools in some areas, not in all cases but in some areas, are used as a vehicle by mainly white parents to put their children in disproportionately white schools,” Ladd said. “Charter schools tend to be more racially segregated than the traditional public schools we have.”

A 2015 paper written by Ladd and her Duke colleagues found a fifth of the state’s charter schools are overwhelmingly comprised of white students. And Hawn Nelson says three-out-of-four charter schools in Mecklenburg County are segregated by race. Some are predominantly black and some white.

Ladd’s paper became part of a report on charter schools that is delivered annually to the N.C. General Assembly after first being approved by the State Board of Education. Some board members criticized the document because they believed it did not offer a positive take on North Carolina charter schools as a whole, and Lt. Gov. Dan Forest said it was “too negative.” Ultimately, Ladd’s research remained in the final report, but the document had been augmented with additional statistics that charter school supporters viewed as “more fair.”

Folks here have looked to other states, too, for a clue about ways to make integrated schools work without significant disruption. Louisville, Kentucky, is often cited as an example because of its popular student assignment plan that blends school choice with factors such as family income, educational attainment, and more. CMS staffers say, from a practical standpoint, the Louisville model may be the closest thing to an analogue they will be able to find.

But Charlotte’s history as a leader in the busing movement, coupled with its dramatic shift to resegregated neighborhood schools make it unique and a popular subject for journalists, policymakers, and researchers.

“The Charlotte-Mecklenburg district has become a cautionary tale about the consequences when a community allows its school system to separate white from black, affluent from poor,” The Washington Post wrote this winter. A 2014 study published in the Quarterly Journal of Economics said “the resegregation of CMS schools widened inequality of outcomes between whites and minorities.” That report found students who attended CMS schools that were isolated by race had lower academic achievement and were more likely to be arrested than peers who attended more diverse schools.

“What makes the Charlotte story so unique,” Hawn Nelson said, “is that it shows what happens when we completely disregard research.”

But Stoops argued that the research isn’t quite so clear. “I think that historical perspective is important but should not necessarily inform the student assignment plan going forward,” he said. “If we’re looking at the historical record, I think you can make the argument that the county was much better off after unitary status was achieved than before.”

ON A BREEZY, pre-spring night, a dozen high school students sat in a drab conference room inside the Charlotte-Mecklenburg Government Center, a pinkish office building home to local municipal offices.

They were huddled around beige tables arranged in a U formation, discussing the topic of busing and student assignment as part of the Charlotte-Mecklenburg Youth Council, a program designed to empower young leaders who are interested in civic engagement. It was a diverse group – black and white and Asian, suburban and urban, poor and affluent. Most of the kids had cell phones sitting on the table in front of them; some slowly spun side-to-side in rolling office chairs.

I asked to sit in on their meeting, and to ask a few questions, because I was curious how they think about diversity in education, broadly, and how they see the current student assignment debate. “Parents and students have very different opinions,” said Jason Kerman, a white 11th grader at North Mecklenburg High School, where about half of the 2,000 students are black. North Meck is sometimes viewed negatively by affluent parents in the northern suburbs, Kerman said, but he values the diversity – and wishes there was even more.

I polled the students: All but two said they attend a school where the majority of students look like or come from similar economic backgrounds as they do. The two exceptions attend specialized magnet programs for arts and engineering that aren’t close to their homes.

The students said they have a more nuanced view of diversity than their parents or other adults do, which they credit to social media for expanding their world view. Black-white and rich-poor dichotomies aren’t all they consider. When they spoke about diverse schools during our conversation, the students around the table regularly mentioned sexual orientation, religion, and specific nationalities.

All of the students said they would prefer to attend more diverse schools, but like the adult policymakers, they struggled to say how they would achieve that balance.

“If your friends are diverse then you get a diverse opinion on life and you won’t just be stuck in the one lane,” said Des’rae Mitchell, also an 11th grade student. Mitchell, who is black, attends a Southwest Charlotte school that’s a 30- to 45-minute bus ride from her home, and says while she appreciates a diverse environment, it comes with tradeoffs. “It’s just always hard to sit here and say busing is always easy because it’s not. There are pros and cons.”

Jalen Lowery, a black freshman with messy hair and braces, chimed in. “If (neighborhood schools) are such a big deal to all these people, then why don’t we have some if you want that, and some schools if you don’t?”

“It turns into politics,” said Morgan Harron, a white sophomore who attends one of the magnet schools.

“Even though we have to go to the schools,” Chryshel Mundy, a black West Charlotte High School senior said with a scoff. The other students nodded emphatically. “What do students know? The ones who have to go to the schools?”

THE SCHOOL BOARD adopted a set of guiding principles for CMS’ student assignment review in late February, after more than 90 minutes of passionate debate about the balance between neighborhood schools and diversity.

The parents were back, once again holding signs about neighborhood schools, and this time wearing green t-shirts that said “Neighborhood School Guarantee” in red letters across the chest. The audience appeared less balanced than the night of the public hearing: suburban parents were out in force.

During the discussion, Tom Tate, a minister by trade and the board’s most forceful advocate for breaking up clusters of poverty, suggested that parents who have different opinions may not be in the meeting room because they didn’t have a way to get there. A couple people from the crowd booed, a break in decorum that drew shushes and glares from both sides.

In the months to come, public education in Charlotte-Mecklenburg will balance the aggregate with the personal, drawing lines that affect individual households to achieve goals that reverberate throughout the nation’s 17th largest school system.

All of the angst to this point has been about the abstract. These broad goals will guide the district and its consultants as they draw specific student assignment boundaries and craft an actual strategy. But no one – not even the school board, as members said that night – really knows where this process will lead. As they prepared to vote on the assignment goals, Ericka Ellis-Stewart, the board’s past chair, spoke in slow, measured phrases.

“We are a community of juxtaposition, a community of dichotomy,” she said.

On that fact, 45 years after Swann, this community is perfectly united.

Oral arguments in Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Education on October 12, 1970.

Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Education, 401 U.S. 1 (April 20, 1971).

This article also will be published in Scalawag.