The Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) Summit, hosted by the Mountain Area Health Education Center (MAHEC) in Asheville, was a game changer for me. Throughout my time as a social work student, I heard some talk about ACEs but the significance of the topic admittedly got lost in the swell of papers, internships, and general stress of school. At the Summit, there was no missing the importance of trauma and its impact on our students and communities; it was front and center of every discussion, presentation, and passing conversation. By the end of the three days, my bag was overflowing with brightly colored pamphlets and my notebook was full of scrawled plans, notes, and names. While I am usually sad to leave Asheville, this time I couldn’t wait to get back and get to work.

Returning to Cabarrus County, my program director and I immediately set up several meetings with the Kannapolis City Schools and Cabarrus County Schools leadership teams. We were intentional on meeting with multiple facets of the school system – the directors of student services, student support services, principals, and superintendents – so that all groups could give their input about how they saw ACEs impacting their school communities and what the best next steps would be.

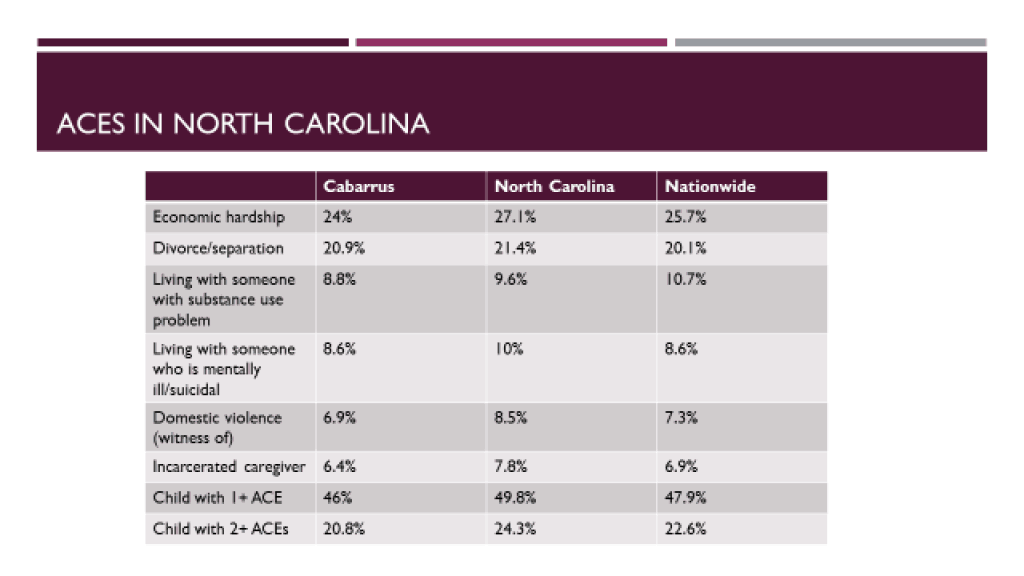

The Students Taking a Right Stand (STARS) Program I manage works closely with approximately 70 young men at four schools who have been identified as students needing additional resources and interventions due to their academic and disciplinary records. We have firsthand experience with the different types of trauma our students experience and the impact it was having on them, behaviorally, socially, and academically. We shared their stories and listened as the administrators showed data that corroborated the trends we were witnessing; those students who experience different types of trauma and chronic stress are falling further and further behind their peers. Following each meeting, everyone agreed that the next step should be to raise the level of awareness of trauma’s effects on our students within our school communities.

In order to figure out where the current level of educators’ knowledge regarding trauma, we surveyed about 300 teachers in the two districts. They received an online survey, adapted from one made available on Buncombe County’s website, asking 34 questions about trauma, its causes, its impacts, and its prevalence in Cabarrus County. While about two-thirds of respondents answered the survey with a seemingly clear sense of trauma and its impacts, the remaining responses were worrisome and strengthened our resolve to bring a heightened sense of urgency to addressing ACEs.

About one-third of respondents disagreed with the statement that a student’s experience of trauma may be different based on their race, ethnicity, or culture. Research shows that perceived discrimination is a key factor in creating health disparities between different ethnic and racial groups. Another statement that cutting, self-harm, and suicide threats are attempts to manipulate others garnered agreement from one-third of respondents. Again, the research shows that these actions are most frequently employed as a coping mechanism, rather than attempts to influence others. These responses alarm me because I fear for what might happen to a traumatized student if they disclose to an adult at their school who holds these views.

I worry that they might be dismissed as overreacting and therefore might not get the resources they desperately need in order to stay safe and healthy. I do not blame those educators who responded this way; I recognize that these are common misperceptions that many individuals hold. However, these beliefs must be addressed in order to ensure that all of our students’ lived experiences are validated, confirmed, and receive an appropriate response.

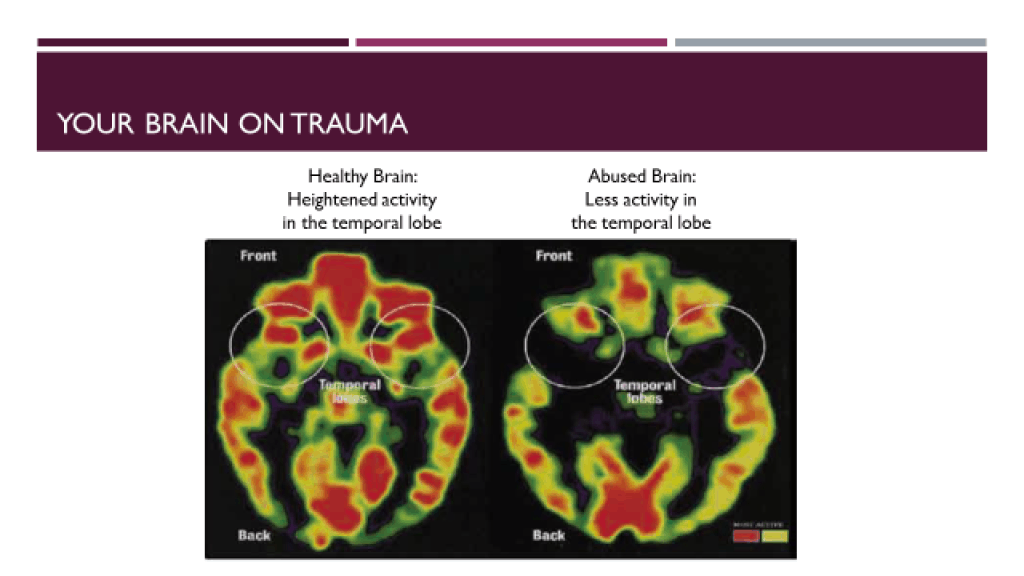

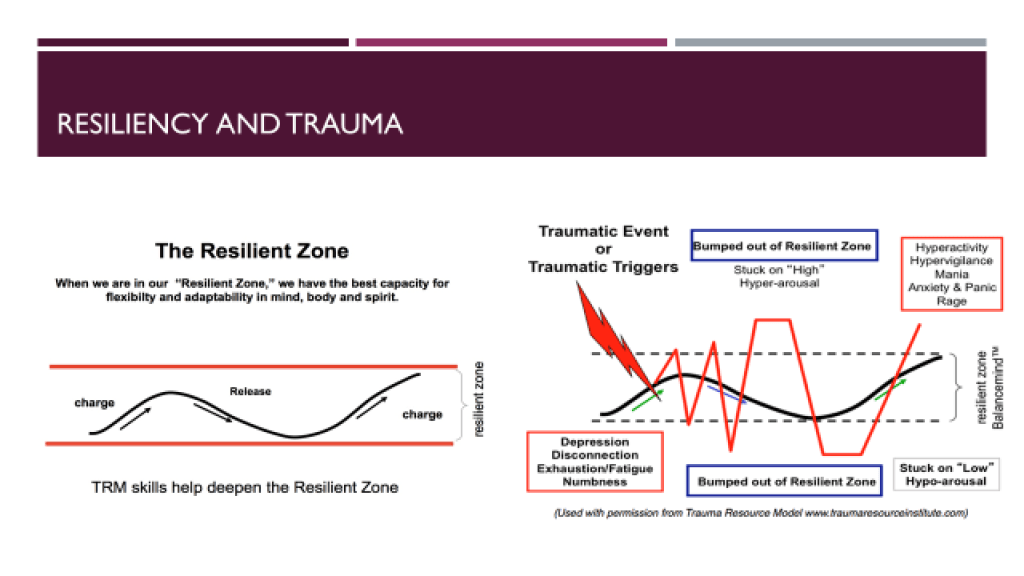

This lack of awareness is not just on behalf of some of our school staff, but also our students. So often those students who are experiencing or have experienced trauma are unable to define exactly what has happened to them. Instead, they may struggle with violent outbursts in the classroom, chronic exhaustion and headaches, and poor academic performances.

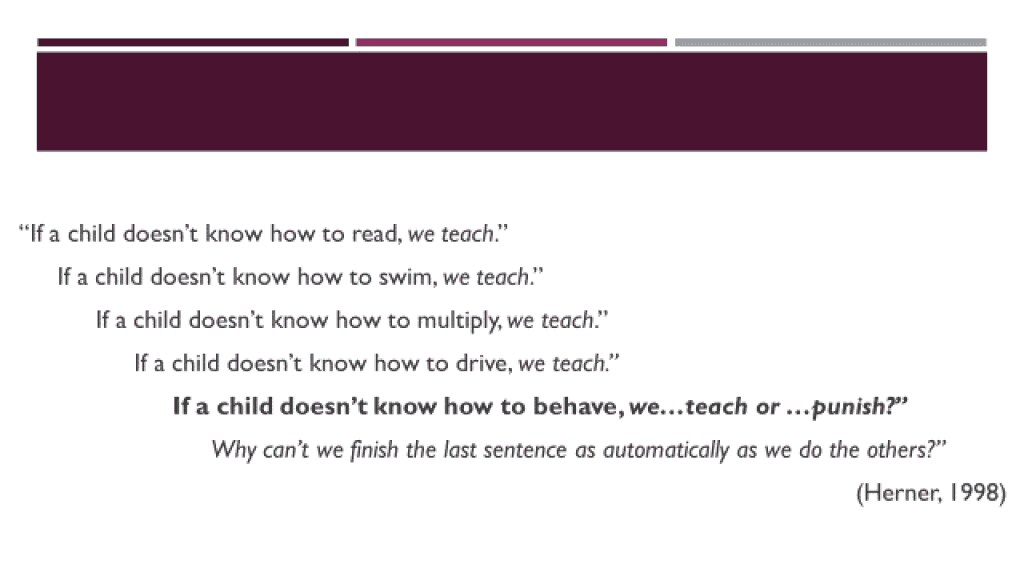

So often I’ve sat with these students, sharing their sense of frustration, and wondered, “What is wrong with you?” But an increased awareness of ACEs and their impact on children’s cognitive abilities helps to reframe those questions.

Recently, a seventh grader I work with tore a teacher’s book and showed little remorse for doing so. Initially, his teaching team and I were very upset with him and struggled to understand why this typically mild-mannered student would behave this way. However, rather than allowing the situation to worsen or focusing only on the punishment component, the student, one teacher, and myself sat down to discuss the situation and what had led up to it, as well as the ramifications following the incident. The key to this conversation being a truly positive turning point was that the teacher and I asked questions like “what happened that week before the book incident? How did you feel afterwards? How do you think your teacher felt?” By asking these questions, rather than solely blaming the student for his actions, we created an environment in which he felt safe enough to disclose some personal experiences that had deeply impacted him that week while allowing him to consider how his behaviors had greatly disrespected his teacher. A week later, a much more encouraging behavior report was given by all his teachers and the student beamed when he heard the positive things they shared.

Moving from “what’s wrong with you?” to “what happened to you?” immediately shifts the questioning from one of blame to one of concern and compassion.

It allows us to better grasp the environment in which this child is trying to function, rather than trying to pinpoint an easy answer to an accusatory question. Because that’s just it. With ACEs and trauma, there is no easy solution, no quick out. Instead, there is pain and discomfort but also understanding and support. Moreover, there is constant room for improvement in how we respond to and address trauma in our schools and communities. But in order to improve and respond in new ways, awareness of the issue must be increased to the point where it is impossible to ignore or deny.

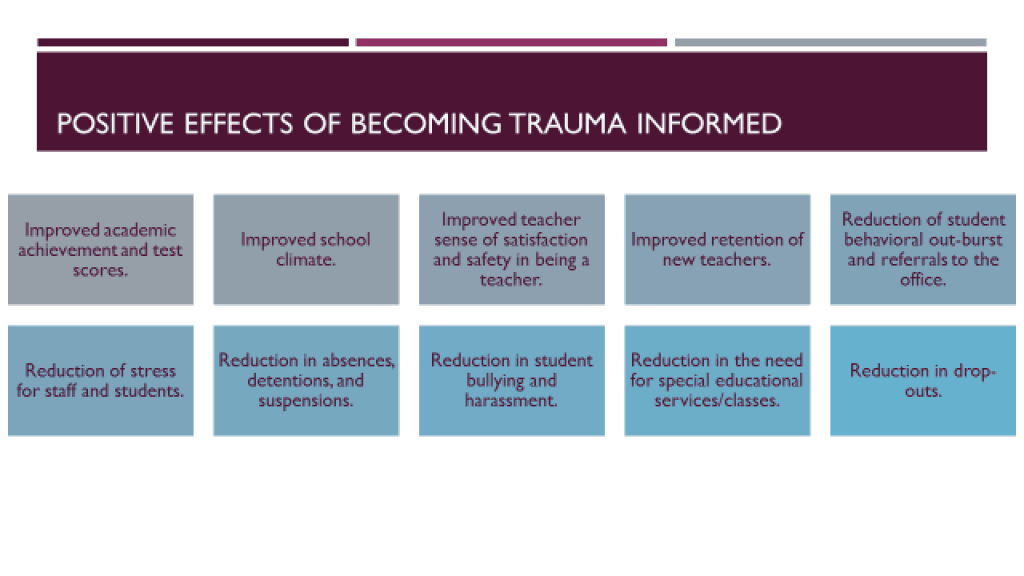

And so, increasing awareness of ACEs and what the schools can do to address trauma is what we set out to accomplish. I read as many trauma-related resources as I could within my first few weeks back from Asheville and developed a brief training on ACEs and trauma-informed schools. The training included an overview of ACEs, their impact on mental and physical wellbeing, and the core tenets of trauma-informed schools. I began presenting on trauma-informed schools to anyone who was willing to listen, which, as it turned out, was a huge number of people. Social workers, school psychologists, principals, and full staff meetings – I met with them all. Interagency and coalition meetings, including physicians, law enforcement, and youth-driven groups received the training. By the end of November, over 200 people had seen the presentation. Countless hours of Q&As were held, and attendees shared their personal experiences with traumatized students and how necessary they felt that this training continued to be held district-wide.

Momentum continued to grow and schools were requesting more information, for both staff and students alike. We continued to meet with district leadership and teachers to discuss how to thoughtfully share information regarding trauma on a community-wide level. We started to plan for a community screening of Paper Tigers, a film we viewed at the Summit and had seen striking similarities between the movie and our realities. Together, we began to implement a tentative blueprint for creating sustainable and meaningful change for our students and teachers alike.