Public schools are taking it on the chin these days, especially in North Carolina. Public school educators face a daunting task on a daily basis, taking children (approximately 55,000 in Forsyth County alone) from every socioeconomic background, with whatever abilities or disabilities they arrive with, and teaching them all the same standard course of study so that they can perform “at or above grade level” or “proficient” on standardized tests.

There are a number of reasons why some children fail to reach that goal. Occasionally, it is because the educator was not the right person or did not have the appropriate training or skills to reach those children. More frequently, the reasons are grounded in lack of support by our elected funding officials – more specifically, their leadership. Over the coming weeks and months, I hope to provide specifics on a number of the direct causes.

When I joined Winston-Salem/Forsyth County Schools in 1981, the K-12 public schools budget was 48 percent of the North Carolina General Fund budget. Today, it is 38 percent of the total budget, and even that number is misleading, in that a growing percentage of the 38 percent is siphoned off to charter or private schools. Charter schools are “public” schools, but they are privately owned with more flexibility and less regulation than traditional public schools. They also have less financial accountability, can pay their leadership whatever they wish, and rent or buy real estate when (in some counties) already paid-for public school classrooms remain vacant, which should seem wasteful to the economically conservative lawmakers who authorized charter schools.

In Forsyth County, the traditional public school system has offered to help charter schools in any way that we can. We have infrastructure that they do not have, at least when they open, unless they are part of a larger, established network of charter schools. Several of the charters that opened here in the County did avail themselves of some assistance from us. While we recognize the competition for students and funding, we also recognize that we share the same mission – educating students to the best of our ability, regardless of the impediments we face in the process.

While the details of operational success or failure of charter schools remains somewhat cloudy, the high level data is fairly clear. Students in brick and mortar charter schools perform, on average, no better than students in traditional public schools on the standardized tests that are used to hold school districts and schools accountable in North Carolina, which should not surprise anybody with any knowledge of the complexities in K-12 education. In fact, it should surprise us that they are performing as well as they are with the lack of infrastructure and state-level support they have received. However, students in privatized virtual charter schools perform, on average, significantly worse than students in traditional public schools. In North Carolina, the leadership of our General Assembly just this year handed more than 3,000 of our students along with 15 million of our state and local tax dollars to two of these schools.

Privatization, by itself, is not the right answer. There are much better answers. Let’s find them together.

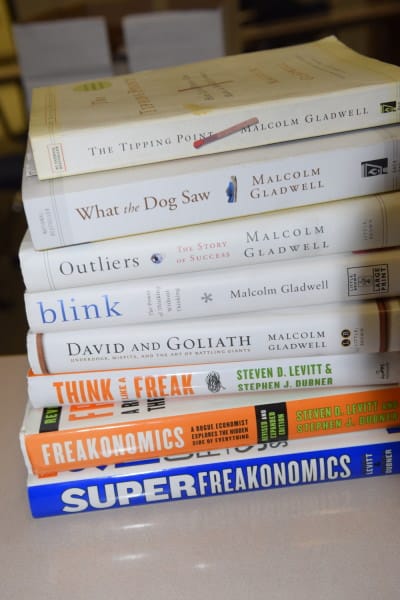

Recommended reading