|

|

In 2021, Mike McNally found himself on an unexpected mission.

As owner of Fairsing Vineyard & Winery an hour outside Portland, Oregon, and then chair of the Willamette Valley Wineries Association, McNally was researching how child care works.

He had spent the last couple of years figuring out how the association could do more than “enhance the prestige of Willamette Valley wines,” he said. The association set up a philanthropic arm to invest in employees of the region’s wineries, and in their communities.

When asked what needs were most pressing, vineyard stewards pointed first to housing, and then to child care.

“My wife would like to be out here working with me, but she’s got to take care of the kids,” McNally recalled hearing in conversations with workers.

Employers across the country are hearing similar sentiments. Some businesses are opening on-site child care programs or subsidizing the cost of employees’ child care.

In North Carolina, an estimated 400,000 working parents are constrained by child care needs, according to a 2022 report from the NC Early Childhood Foundation. Insufficient child care is costing the state $3.5 billion annually, and the country $122 billion, according to a 2023 ReadyNation report. Local and statewide chambers of commerce are speaking about the need for child care.

But McNally’s journey did not end at acknowledging the need, holding a news conference, or even connecting his business’s own employees to child care. After two years, Primeros Pasos, “first steps,” is just getting started in building a child care system that serves Latino communities across the region.

‘An ideal partnership’

McNally was introduced to Jaime Arredondo, executive director of Capaces Leadership Institute, a nonprofit serving Latino communities in the Willamette Valley. The organization has been rooted in labor organizing and immigration raid resistance starting in the 1970s.

“My father was one of thousands of folks that came into that place in the ’80s to get immigration assistance,” Arredondo said.

He’s been involved in community-building efforts for many years. He described himself and McNally as “an ideal partnership” in some ways: a grandfather “trying to pay it forward,” and “a younger guy who’s got kids in pre-K.”

“I’ve been in the movement, and I’ve been taught from an early age, take the long view,” Arredondo said.

He located an available lot and asked whether McNally could find funds to build a child care program. He then went on paternity leave.

Though he didn’t know how this partnership would evolve, his experience as a father to young children made him interested from the jump.

“There’s a time and a place for everything, and I wonder if he would have caught me at a younger age if I would have seen the potential in this,” he said.

An aha moment

During Arredondo’s time off, McNally got to work. He took a self-built crash course in early care and education.

He learned about Oregon’s system: Child Care Resource & Referral agencies, the early childhood workforce registry run by Portland State University, Early Learning Hubs, child care subsidies and public preschool programs and quality rating scales.

Then he turned to experts. McNally took a trip to visit his niece, Amy Schmidtke, director of program development at the Buffet Early Childhood Institute at the University of Nebraska, to learn more about the systemic issues leading to a broken child care market. There, he had an aha moment.

He left with a shift in his thinking. “It’s not about the building, it’s about the workforce,” he said.

By the time Arredondo was back from paternity leave, McNally knew he had to persuade him to think bigger than one building or one program.

“Until we build the workforce, we don’t have anything,” McNally said. “… I sat down and I said, ‘Hey, man, I think we need to turn this thing upside down.’”

In the last two years, that’s what Primeros Pasos, a consortium working to “create best-in-class early childhood education and care for Latina communities in Marion, Polk, and Yamhill counties,” has been doing.

McNally and Arredondo knew there were several organizations doing important work already that needed support and coordination.

“(We were) two dudes coming together with no experience in the subject other than what they’ve read and what they’ve studied, and so we knew that we needed to bring people together that know how to do this work,” Arredondo said.

Primeros Pasos

McNally and Arredondo formed the group of regional early childhood organizations, agencies, and partner institutions. Capaces Leadership Institute sits at the top — with the closest proximity to Latino communities.

Instead of individual organizations deciding what to work on and then looking for funding, the community is at the center of those decisions.

“It’s the Latino organization, the Latino community, driving it, not state and county agencies,” McNally said.

The group conducted a needs assessment, located the existing resources, and created a strategy with measurable goals along the way.

That assessment found:

“Approximately 7,000 preschool Latino children (0-4-year-old) reside in this area. Early learning programs are available to serve only 1-in-8 infant and toddlers and 1-in-4 preschoolers. Only 33% of the available programs have conducted quality assessments, and only 15% have achieved a 3- 4- or 5-Star rating with the Spark Quality Rating & Improvement System.”

Primeros Pasos plans to serve 1,500 more children, enroll 300 new teachers in college and community-based training, open 150 new family child care homes, and create a culturally specific curriculum in the next five years.

The consortium has already secured $300,000 from the Child Care Alliance to train providers, $300,000 from the state Department of Early Care and Learning to create a scholarship cohort of 25 students studying early childhood education at Clackamas Community College, and $1.5 million from the state to build capacity in organizations in the consortium to focus on the project.

The five-year project is going to cost about $70 million, which includes state funds going directly to programs serving children from established channels such as the state’s Employment-Related Day Care and Preschool Promise programs.

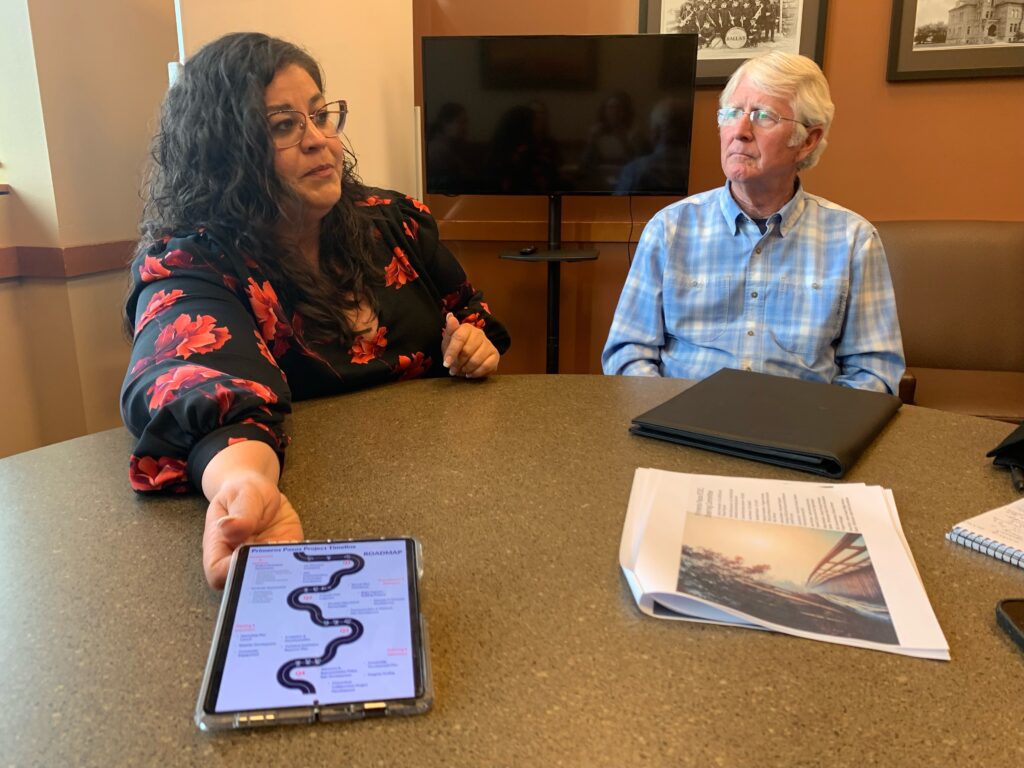

The program’s manager, Lucy Escobar, has been at the head of Primeros Pasos for less than two months. But she’s been working as a coach with child care providers for seven years.

“This is a legacy project,” Escobar said. She’s worked with providers like Herlin Alvarez, who just opened a Early Start Preschool and Child Care Center in Salem, Oregon, but operated a family child care home for seven years beforehand.

Escobar started working with Alvarez at her dining room table, helping her navigate the complex systems and rules of child care licensing.

“Our vision was that one day, she would get to open her center, Escobar said. “And last year, we cut the ribbon.”

Primeros Pasos is now surveying the needs of a new cohort of in-home providers to support them with training and mentoring all in Spanish, in the coming year.

The project has four main strategic pillars: early childhood workforce and development, Latino-specific curriculum and learning plans, existing provider development, and recruitment of new educators and providers.

“By recruiting and supporting Latinx educators and providing them research-based resources and tools that are culturally relevant and developmentally appropriate, we can create an environment that doesn’t just acknowledge diversity but celebrates it as an essential component, alongside developing healthy mental and emotional relationships and stimulating brain development for our future generations,” Escobar said in an email.

The project’s consortium has a steering committee with a member from each of the consortium’s organizations: Capaces Leadership Institute, Child Care Resource & Referral, The Marion-Polk and Yamhill Early Learning Hub, Oregon Child Development Coalition, and the Willamette Valley Wineries’ Association.

“Each individual has brought their resources and perspective to the table, fostering the sharing of ideas, experiences, and a genuine care for the future of Oregon,” Escobar said. “I don’t see egos or private agendas; instead, I see a community willing to unite and collaboratively create a better Oregon for both the present and future generations.”

The project just brought on a public relations manager and outreach coordinator, is in the middle of launching a website, and is gearing up to welcome the in-home provider cohort.

Investing early and holistically

Even though the project in its first phases, Arredondo is not losing the long-term vision.

“When we invest at an early age, and when we invest holistically, I just can’t wait to see what kind of leaders this is going to produce in our community,” he said.

There are lessons outside of the region, and outside of Oregon, on cross-sector leadership going beyond immediate needs and solutions, he said.

For Arredondo, the project is a full-circle moment. His father worked in the vineyards just like the ones that have spearheaded Primeros Pasos.

He’s now headed toward another paternity leave to welcome his fourth child into the world in two weeks.

“It’s like growing a superpower, because you see things you didn’t see before,” he said. “I really believe it does take a village, whether that’s a village, or a big community, like our big region, to make this work.”