|

|

Dominic Roberts knows the gripping feeling of shame and guilt when he needs to ask a teacher for an accommodation.

Roberts, a high school senior, has a 504 plan that provides for accommodations in class, but sometimes teachers don’t look or remember. It’s a challenge, because our system of education is standardized, yet people are not. Teachers must provide specialized services and accommodations to neurodivergent students if they want to perform their essential function – to teach.

Roberts knows another feeling, too. He knows what it’s like to be one of only three Black students in one of his AP classes. The shame and guilt he feels having to ask for accommodations is amplified while he represents the disproportionately low population of Black students in advanced courses.

“You didn’t look at it, but it should be the standard to look for and constantly check if the student needs accommodations,” he said. “Because that’s your job as a teacher.”

It’s also the law. And it’s just one of myriad ways the education system can short the students it owes the most – whether it’s because of race, neurodiversity, or socioeconomic depression.

Enter LENS-NC.

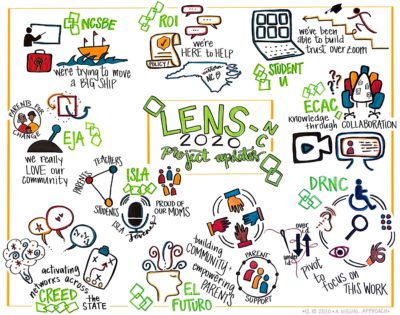

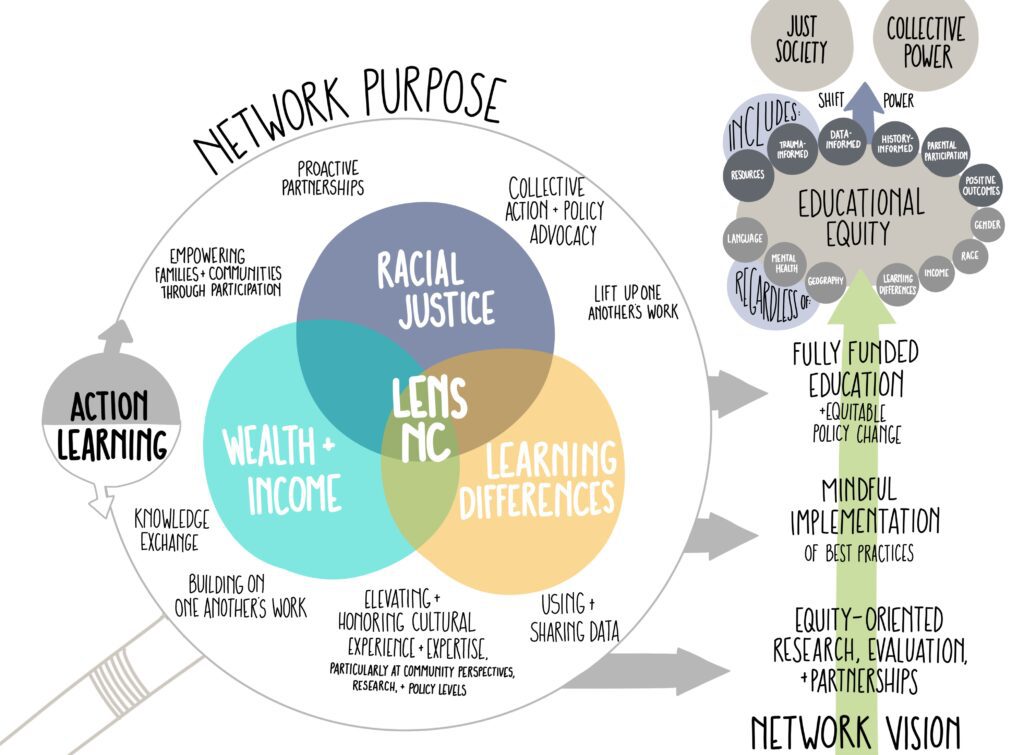

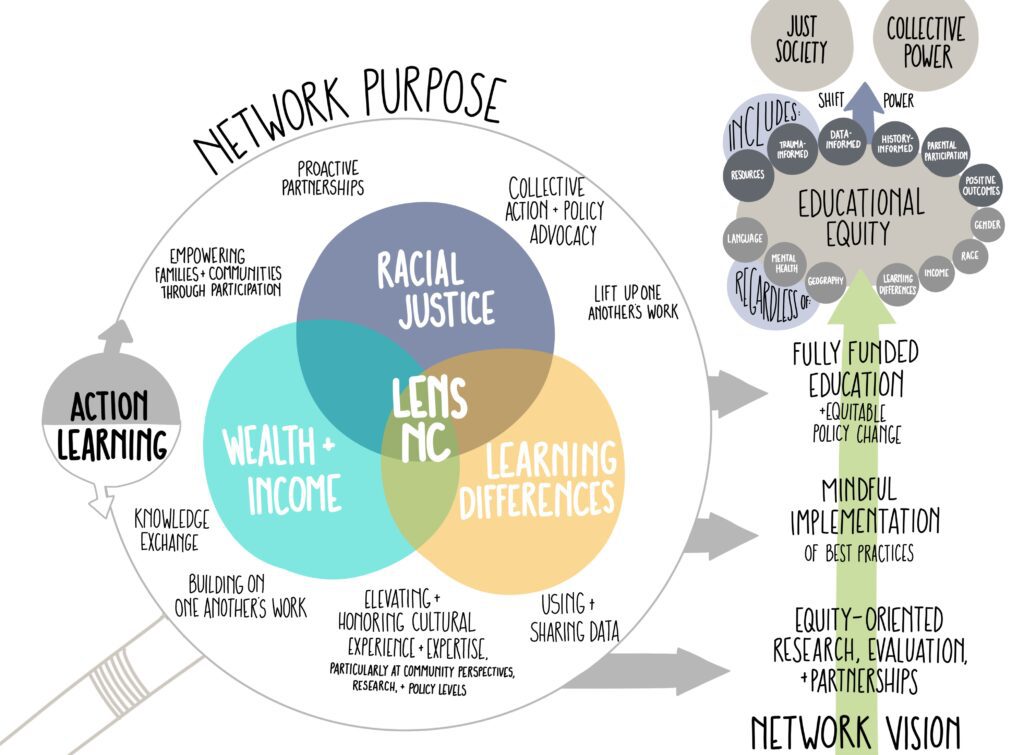

As this cohort, funded by the Oak Foundation and facilitated by MDC, begins its third year of work, it’s celebrating a dual approach. And the symbiotic relationship between those approaches might be what uncovers solutions for students living at the intersection.

The network provides opportunities for organizations to learn together, learn from one another, address common challenges, and explore opportunities to amplify effective strategies for change at the classroom, school, community, district, and state levels.

“This was always billed as a learning and action network,” MDC Program Manager Elyse Griffin said. “MDC has always called it that. But I think at different times, we are doing one or the other, more.”

Who are LENS-NC?

MDC convened LENS more than two years ago, intending it as a hybrid cohort that would meet in-person several times a year and check in monthly online. But students were still learning from home when the group held its first meeting in 2021, so it has become a largely remote experience. Two weeks ago, in fact, was the group’s first in-person event, an informal coffee house experience that preceded an in-person working session scheduled for this week.

Despite the sometimes sterile experience of meeting via online conferencing platforms, MDC has helped build a camaraderie among the cohort – and the experience has launched multiple partnerships among cohort members.

Each member has set its own goal for the LENS-NC experience. Here are the 20 members and their LENS goals:

Association of Mexicans in North Carolina (AMEXCAN)

Its LENS-NC approach focuses directly on leveraging student voices, needs, and concerns through community-based and seasonal programs at participating Pitt County schools. As a result of joining LENS, AMEXCAN has reinstated its Jovenes en Acciones (Youth in Action) program. It’s now called the Lideres del Futuro (Leaders of the Future) Program and centers on empowering high school and college students to form part of AMEXCAN’s initiatives to act as a support system for students at the K-12 level.

Boys and Girls Club of the Coastal Plain

Through LENS, it seeks a better understanding of needed training and best practices to better serve youth, especially those with learning differences, in academically enriched afterschool environments. Among its goals is further connecting and improving school-based partnerships to streamline the impact on programming, training, and continuity of service for students in its programs.

Center for Racial Equity in Education (CREED)

After completing a phase one goal, its work now centers on “educator understanding of equitable practices and learning environments that address bias and promote cultural responsiveness in the classroom.” In particular, CREED is building resources (asynchronous and live trainings) based on the Playbook for Learning Differences it created in phase one.

Education Justice Alliance (EJA)

EJA is studying the school-to-prison pipeline and how it disproportionately affects students with learning differences. It aims to provide parents and communities with knowledge and tools to address inequity. EJA asks questions related to how biases and stereotypes about students with learning differences contribute to disproportionate representation in the school-to-prison pipeline, how failures to adequately support and accommodate the needs of these students feeds the pipeline, and how schools and communities can work to dismantle the pipeline.

A community organization in Durham, it is using the LENS experience to provide services within the school system for Latinx students with ADHD and their families. It seeks to support parents and empower Latinx students. It is running a class called El Faro, where Spanish-speaking parents of kids with ADHD learn about the condition and strategies to support their children. El Futuro also provides a coach who works with children and families to implement strategies at home.

Empowered Parents in Community (EPiC)

Its goal is to influence systems to reduce race and income disparities in educational outcomes among students with learning differences, with a particular focus on Black children. To that end, it seeks a better understanding of the North Carolina special education system for K-5 students, as well as early childhood programs.

Exceptional Children’s Assistance Center (ECAC)

It is using the LENS experience to learn more about racial inequities and the negative impact on children with learning differences and those children who receive special education services. It is intentionally incorporating other LENS partners’ work in its own organizational work, and vice versa, so that the completed scopes of work are used and can continue to be disseminated and grow.

Disability Rights North Carolina (DRNC)

DRNC seeks to better understand and impact the special education system in North Carolina, and specifically address the reasons students of color with learning differences are excluded and pushed out of school. It wants to understand how parents experience the special education system, including the barriers they face in advocating for their children. Among the responses to its learning, DRNC is improving its trainings and making information more accessible and useful to the public.

It is studying the juvenile justice system, specifically the over-representation of children and young people of color and students with learning differences. It is focusing on improving training activities for parents as an important component to helping marginalized students with learning differences and their families understand a host of issues. These include the connection between involvement of marginalized students with the juvenile justice system and student behavior, bullying, school attendance, school performance, school culture, student ethnicity, family engagement and advocacy, and school and law enforcement personnel training.

Hispanic Liaison of Chatham County

It is working to understand the policies and laws surrounding education, with a focus on students with learning differences and the IEP and 504 plan processes. On a state level, it is trying to understand possible impacts from fully funding Leandro, as well as other ways in which policy can affect more equitable education for all students. Locally, it is organizing Latinx parents to bridge the gaps between them and school systems.

Immersion for Spanish Language Acquisition (ISLA)

ISLA aims to support students with diagnosed learning differences and autism by supporting parents as they navigate the school system and engage with other resources (therapeutic resources, community resources, etc.). It is working to engage parents with experience in supporting other parents and working to create learning opportunities and environments that meet their needs and better equip them to advocate for and support their students.

Men and Women United for Youth and Families

It is exploring ways to provide assistance to the educational system without provoking defensiveness, as well as looking for best approaches to partnering with schools. Some of the questions it is asking are: (1) What accountability is present for public schools and the role of local school boards/the Department of Public Instruction in the process? (2) How many students have IEP/504 plans? (3) What are the laws pertaining to equal protection for all students?

North Carolina Justice Center – Every Child NC coalition

The North Carolina Justice Center’s LENS project supports the Every Child NC

coalition. This project provides mini-grants, via the Partner Support Fund, to

grassroots groups to start local chapters of the Every Child NC coalition to

continue to build local support for state level reforms as part of the

Leandro case. Students with learning differences and those at the intersection of

race, poverty, and learning differences in particular will benefit from the

implementation of this plan. The project expands the Justice Center’s current

work of building grassroots advocacy for educational equity across the state.

North Carolina State Board of Education

The Board seeks to better understand how the state education system can ensure equitable opportunities for marginalized students with learning differences. Its explicit focus is on eliminating significant disproportionality in special education through discipline, identification, and placement measures. It is holding monthly webinars, working with equity officers and Exceptional Children leaders, and preparing guidance documents. Ultimately, it aims to build capacity and intentional focus on educational equity to identify and sustain equitable practices throughout the state.

Operation Xcel wants to better understand the systems in which parents and guardians can interact with their children’s schools and advocate for students to help gain increased understanding and higher academic achievement. Specifically, Operation Xcel would like to better understand how to create a toolkit for parents to advocate for their children within the school system. Additionally, it wants to better understand the MTSS process and the ways in which it (as an afterschool and summer program) can help implement strategies to support students.

Profound Ladies’ focus is on the North Carolina school system and its impact on Black, Indigenous, people of color (BIPOC) female educators. The organization seeks to better understand the challenges these educators face and how they can be addressed. Retention is a key area of concern for Profound Ladies, and they are working to provide support, resources, and advocacy to improve retention rates for BIPOC female educators. By promoting a more inclusive, equitable, and supportive system, Profound Ladies aims to empower these educators and benefit the students they serve.

Public School Forum of North Carolina – Dudley Flood Center for Educational Equity and Opportunity

The Flood Center seeks to shed light on how racial inequities affect the experiences and outcomes of students, especially those with learning differences. Its proposed project focuses on addressing systemic racism, the root cause of educational inequity for students of color and those from lower socioeconomic backgrounds.

Rise and Shine serves families of low-income students and students of color with learning differences. It provides professional development for staff and tutors based on culturally responsive teaching. It has also had student-led conferences at the end of the third quarter grading period for students in grades 4-12, with parents and tutors present, to discuss accomplishments and challenges, talk about interests and plans, and set goals for the upcoming quarter/year. The organization also advocates for monthly parent meetings to provide information and training on relevant topics related to their child’s education, opportunities for personal growth, and goal setting.

Rural Opportunity Institute (ROI)

ROI wants to impact schools and shift how school systems and the people they work with create more restorative practices and reduce incidences of punitive discipline. It wants to ensure that policies serve students with learning differences, students with trauma, and students who are marginalized in other ways. One of its initiatives is administrative advocacy — for example, helping schools and families get more information and support in navigating healthcare/Medicaid systems.

Student U seeks to understand how to better support families of students with learning differences and help them navigate the IEP process and advocate for their students. It also focuses on individually supporting students with learning differences in the classroom.

The intersection, and LENS’s learning journey

The intersection of race, neurodiversity, and income isn’t the only multidimensional aspect to this work. The LENS members consider these permutations through multiple lenses.

“What does it mean to be a marginalized learner, what communities are impacted?” said Jason Marshall, the LENS-NC program director at MDC. “So that’s an equity and justice lens. And then the other area is brain science. What do we know about just learning in general? That’s a whole area of study. So I think, as educators, we’re trying to do our best to study those two areas, and in studying them, also see how they overlap.”

When LENS began in 2021, its nine members met on Zoom during the COVID-19 pandemic. It was a world of remote learning and masking – as well as demonstrating. In the aftermath of the police murder of George Floyd in 2020, the group felt a wave of energy toward justice work. Many group members had been deeply engaging in justice work for a long time.

At that time, there was a call to action. Many of their individual group projects mirrored that. But outcomes for students remained out of reach. In year two, the call to action hung in the air but, as the cohort grew to 20, there was also a call for further study.

“I would say year two was finding content areas to study,” said Marshall, forecasting what this third year may hold. “And year three is really around integration – integrating those two content areas. And then within that is our whole work – how do we do it?”

“I would say year two was about finding content areas to study and practice but the intentionality behind how we approach relationship building and supporting the creation for conditions of safety — so our individual and collective learning can even happen — has been equally, if not more, important,” he continued.

“And year three is really around integration – integrating those two content areas, relationship building — social emotional learning sprinkled throughout our work, evolving toward a collective action, and lastly a thorough evaluation of our efforts. And then within that is our whole work.”

MDC is working in partnership with RTI for its evaluation. It also credits local partnerships with we are (working to extend anti-racist education) and A Visual Approach as instrumental in helping the network evolve.

In search of a unifying theory, and a lasting impact

Among the breadth of learning opportunities is an exploration of theories of learning. The cohort will spend time this year establishing a grounding principle or approach for the work. Right now, that looks like a study of universal design for learning, using the CAST framework.

As the cohort moves through the work, activities include convenings and webinars, network mapping, creating and executing learning plans, engaging in peer learning activities, inter-organization collaboration, and community engagement.

MDC helped the cohort establish five “Leading and Learning” groups, focused on policy, data, educator engagement, language and communication, and resilience.

Along the way, it is carefully documenting the work.

“We have to capture our learning while we’re doing it so that, hopefully, if we’re talking to people after … we’re talking about what was our problem, what we attempted to do, and this is our process of how we’re practicing to attempt to get to this (next) place,” Marshall said. “So maybe you could look at us as a dynamic example of attempting to do this work, and start your own journey.”

The group’s work has continued through leadership changes at MDC and expansion of the cohort. It’s not unlike the situation in many districts, with changing leadership and student enrollment. It’s a reminder, Marshall says, that how the work gets done is as important as the work itself.

“We have to be in the practice of continuing to do it,” he said. “It helps us – not necessarily know what the answer will be – but know that our answer is to continue our process of reflecting and unlearning.”