Share this story

- “Child care in and of itself should be seen as a public good, like parks and libraries and K-12 education — learning doesn’t start at 5 or 4,” says @muffy_grant about a report from @ncecf. Here’s our overview. #ECE #earlychildhood #nced #ncpol

- “There really can't be a solution without significant public investment” in early care and education, says Muffy Grant of @ncecf. Learn more about the foundation’s report on the role of early care and education in NC's economy. #nced #ncpol

|

|

Child care availability and affordability are the key to the state’s economic future, a new report from the North Carolina Early Childhood Foundation (NCECF) says.

NCECF surveyed parents in October 2020 to learn how the COVID-19 pandemic was affecting how they made choices about child care, employment, and continuing education. The 802 respondents made up a representative sample of working parents with children from birth to age 5 across North Carolina. A new analysis of those results was published on Dec. 1, 2022.

The report finds North Carolina’s economy to be “inextricably linked” to the child care industry. The limited accessibility of child care contributes to “divergent economic futures for families,” it says.

‘Dusty and dry’ child care deserts

Almost half (44%) of families with children in North Carolina live in child care deserts, the report says.

Child care deserts are locations where there is less than one available slot in a licensed child care facility for every three children from birth to age 5.

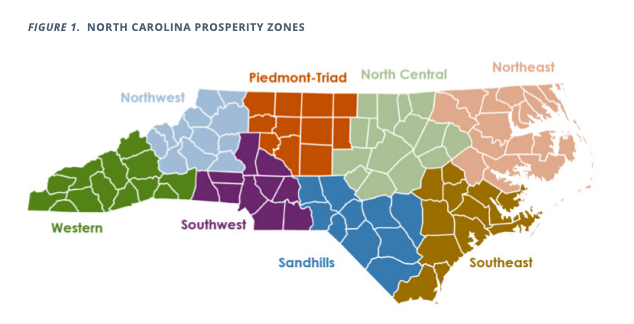

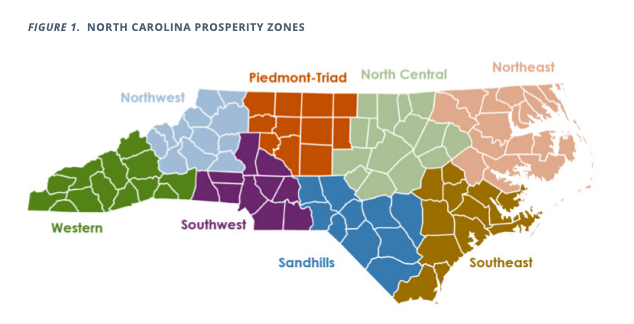

“It’s easy living in a major metropolitan area to not think about how uneven the distribution of resources is and how dusty and dry the child care deserts really are in many of the Prosperity Zones across the state,” Muffy Grant, executive director of NCECF, told EdNC.

Prosperity Zones (PZs) are regions defined by the North Carolina Department of Commerce to coordinate services across state agencies and make them more accessible to residents.

NCECF identified four PZs that would particularly benefit from improvement in child care availability and affordability — the Sandhills, the Piedmont-Triad, the Northeast, and the Northwest — given other challenges their residents face.

Families with children in those four PZs are subject to higher rates of unemployment and lower median household incomes. They are also more likely to experience negative outcomes related to the social determinants of health.

More than 50% of children in the Southeast and Piedmont-Triad live in a child care desert.

“There really can’t be a solution without significant public investment in the early care and education system,” Grant said. “Child care in and of itself should be seen as a public good, like parks and libraries and K-12 education — learning doesn’t start at 5 or 4.”

Untenable choices

The authors of the report found that parents of young children are making life choices based on the availability and affordability of child care. They say “this is especially pressing for 80% of Black, 50% of White, 45% of Latina, and 40% of Asian American/Pacific Islander mothers who are their family breadwinners.”

Women were found to make up the majority of part-time, low-wage workers in many communities and are disproportionately the primary caregivers of children in the state.

This presents them with unique challenges to accessing child care. They typically don’t have paid leave that would enable them to take time off work to care for children, and child care is often out of reach for them financially. Women in this position may have to leave the workforce or school and rely on public benefits to care for their young children.

To examine how socioeconomic status (SES) affects the choices parents make when it comes to child care, NCECF categorized households as “low SES” if they met one or more of the following conditions: working parents who had a high school education level or less, met federal poverty guidelines for 2020, or used public assistance.

Almost half of low SES households used childcare services. Most of those relied on informal care provided by friends, family, or neighbors.

Such care was preferred for women in low SES households because it offers flexibility for working hours and attending school, the NCECF says.

Parents across the socioeconomic spectrum shared similar reasons for choosing informal care — such as personal preference, affordability, COVID-19 concerns — but parents in low SES households were more likely to report going to school than those in higher SES households.

“Single, low-SES women are leaving postsecondary pathways directly as a result of lack of child care,” Grant said. “We really want to ensure that they have access to a high quality, affordable, available, mixed-delivery childcare system in our state that is responsive to the needs of families in their many forms.”

Interestingly, parents with a two-year or four-year degree were likely to be in low SES households. And while survey participants with advanced degrees were more likely to be in higher SES households, 40% of them were still low SES.

Grant attributes this to the burden of student loans.

“And then you layer on top of that the fact that child care costs even more than the average tuition to a four-year degree-granting institution in the state of North Carolina,” Grant said, “it’s just not a tenable situation.”

Child care at the nexus

NCECF estimates that 400,000 working parents across the state are constrained by child care needs. This can affect the choices they make about whether to pursue postsecondary education, participate in the workforce, or even pay for things like food and housing.

These constraints were evident in NCECF’s survey findings: 45% of parents with young children were dropping out of college/training or declined training.

Grant pointed out that lack of child care poses a real threat to the state’s economic future, including the myFutureNC goal of ensuring that by 2030, 2 million North Carolinians have a high-quality credential or a postsecondary degree.

“We as a state have made this huge investment and are all supporting and cheering for myFutureNC and the 2030 attainment goal,” Grant said. “I don’t know how [reaching] that is possible without addressing this foundational issue first.”

The authors of the report argue “economic recovery across the state will be dependent on child care as a key strategy to support workforce development, which in turn, will benefit local business owners with skilled workers.”

They urge policymakers to give “sustained attention to child care affordability and availability for families, especially for mothers in low SES households who have children under the age of three.”

While the survey was completed in 2020, Grant said she hopes that the lessons learned from the early stages of the pandemic will motivate stakeholders to make new choices about how to address continuing child care challenges right now.

“How are we gonna stabilize the system as it is, and how are we going to transform it so that in the future, we are not up against this freefall into oblivion for young children, caregivers, providers, and the economy writ large?” Grant asked. “Child care is at the nexus of our attainment goals and our economic development hopes and dreams of mobility for caregivers and children.”

The report concludes by highlighting the importance of thinking regionally with a focus on low SES households and women when policymakers try to answer Grant’s questions. It goes on to say, “Regional differences aside, there is a need for ensuring a robust child care system that is available and accessible to meet the diversity of families’ needs, especially for parents of infants and toddlers.”