Share this story

- “I don't know if I expected all of this.” The story of four dedicated educators and their journey from uncertainty to confidence at the #NCAIM2022 Conference. #nced @AIM_NCDPI

- "To have people embracing and encourage you like that, that was awesome." From anxiety to the power to change lives: four Bertie educators’ journey at #NCAIM2022 #nced @AIM_NCDPI

|

|

Four educators from Bertie County Schools are westbound, headed to the Raleigh Convention Center with equal parts excitement and curiosity, on a Tuesday afternoon. Their destination: the Department of Public Instruction’s second annual A.I.M. Conference.

The conference draws more than 1,000 educators from more than 100 districts across the state. It’s a chance for district and school leaders to meet, learn from, and collaborate with their counterparts and with local and state leaders. As state-organized education conferences go, this is the biggest. As attendees go, Bertie’s delegation is among the smallest.

Bertie has about 150 educators working in schools. Sending away these four people, including two principals in a district with just seven schools, for half a week is a significant investment of resources.

“There’s a million things back home that I need to be doing,” says Linda Bulluck, the district’s executive director for curriculum and instruction. “And I know they’re going to be waiting for me when I get back because nobody else is going to do it.”

What these four are leaving behind is not all that’s on their minds. One is wrestling nerves because she’ll start as a first-time principal just two days after returning home. Another is anxious about a presentation she’ll deliver at the conference.

All of them are a little curious. With a conference agenda spanning nearly 40 pages, there’s a lot of ground to cover. Will they find their way to the information most useful for their district? Will this trip be worth it?

They aren’t making the trip alone, though. As their doubts quiet and their questions get answered over the four days, they are reminded that a higher power is along for the ride.

A district story

Bulluck is the portrait of a district leader. She always seems calm and poised. As the conference gets under way, though, she admits that some things are worrying her. Among them is an increase in behavioral challenges in middle and high schools which seem more common statewide since kids returned from learning at home. Bulluck wants badly to figure out how to meet kids’ social and emotional needs.

She hopes she’ll learn some strategies during one of the SEL-centered sessions, but she’s also on the hunt during her “lunch and learn” time.

North Carolina’s 115 public school districts are grouped into eight regions. Each of the first three days at A.I.M., these eight regions, along with charter schools, lab schools, and the state’s virtual school, break out into 11 cohorts at lunchtime to share challenges and victories.

For two days, Bulluck shares both, but the answer to her SEL questions eludes her.

The challenges facing Bertie County Schools aren’t so different from those in other schools in its region — which is to say, they are weighty. Much of the northeast part of the state has a declining population, so the schools aren’t just trying to educate kids. They’re trying to build a lifeline for the region’s prosperity.

Bertie, one of 17 districts in the Northeast region, is a mostly Black district – 83% of its students and 66% of its teachers are Black. It sits in a Tier 1 county where the average annual wage of $34,023 is eighth-lowest in the state. A third of the county’s children live in poverty, and half of the county doesn’t have access to broadband.

But the district also has successes to share. Three years ago, the school board named county native Otis Smallwood superintendent. Since then, graduation rates climbed to an all-time high of 92%, elementary and middle schoolers who take end-of-grade exams grew 13 percentage points, and six of the seven schools met or exceeded growth — all during a pandemic.

Bulluck isn’t boastful, but the point of breaking into cohorts is to share successes like these. So she does. She’s hoping someone will share their success with social-emotional learning for older kids.

“We’ll see,” she says on Day 2, still searching. In the meantime, she’s finding lots of reasons to stay calm. For one thing, meeting with her cohort brings relief when she hears other districts’ challenges. They sound an awful lot like her own.

On Day 3, she attends a session on equity – about reaching every student. The presenters, from Edgecombe County Public Schools, happen to be from her region.

It’s there that Bulluck learns about things districts tend to do that center adult needs and miss the mark on student needs. She’s intrigued.

“And, really, that morning session was about SEL,” she says afterward. It’s exactly what she came for. She’d been in a cohort with these presenters all week, but she needed to sit in their conference-wide session to get her answers.

“He places people in our path that we can make connections with,” Bulluck says, giving credit to God that she happened upon that session. “That’s a powerful connection. I talked with the presenter, and we’re going to connect. She invited me to come to Edgecombe County. I believe that was divinely appointed.”

A principal story

The next day, as Bulluck rides the escalator up toward the main ballroom, she’s thinking about her district’s newest principal. Chandra Eley has shown a lot of leadership ability over the years, but she has never led a school. It’s Saturday, and Eley will sit in the principal’s chair on Tuesday.

“She has confidence, and she’s going to be great,” Bulluck says, “but she’s just a little nervous right now.”

Eley has a plan for her time in Raleigh. As an administrator, she wants to learn everything she can about the state’s push to align literacy instruction with the science of reading. Bulluck says implementation is going well in Bertie, but it’s important that administrators understand the state’s “why” and “how.”

“The biggest concern was from the leadership,” she says. “If you’re holding me accountable for making sure this is implemented, why not give me the training so if teachers start complaining, at least I have an intelligent response as to why this is so important.”

Eley listens dutifully in her first session, on bringing the science of reading research into core literacy instruction. But, in truth, Tuesday is what she keeps thinking about.

Fortunately, she got what she needed from the session before the presentation even began.

During ice breakers, Eley shared about her promotion and her nerves. That’s when, she says as she points to the goosebumps on her arm, God showed up.

Eley took a non-traditional path to the principalship. She started her career working in Head Start, rotating through jobs including stints as an assistant to the nutrition manager and helping office leaders with grant writing. When she heard that Head Start could close, she started seeing visions. The visions were varied, but they all included her being her oldest child’s first teacher and her opening a day care.

Eley said she came up with a lot of excuses not to pursue that vision.

But one at a time, the excuses vanished. Her mom decided to go back to work, and Eley realized she needed child care. She opened a center and, as her son grew, she took classes to earn her bachelor’s degree and started teaching.

“God removed all of the obstacles,” she said. “He delivers on his word, and his word does not return void.”

Despite that faith, as well as a master’s degree and experience as an instructional coach she picked up along the way, she still wondered about her non-traditional path to the principal’s chair. When she voiced this to her table mates during that ice breaker, she heard a clamoring of affirmation that gave her those goosebumps.

“God put people there for that affirmation,” Eley said. “Each time he is directing my stance, and he continues to direct my stance so I am where he needs me to be. I’m thankful for that.”

The affirmations continued throughout the conference as Eley walked the lobbies and halls of the convention center and those table mates passed her with renewed shouts of encouragement.

“To have people embracing and encourage you like that, that was awesome,” she said. “Because, you know, these are my colleagues. I don’t know them, but we’re still in this business together, in this field together working. I didn’t know it, but I needed that affirmation.”

She got a lot out of the literacy sessions, but when she talks about getting what she came for out of the conference, it’s the boosted confidence she’s taking home.

An immigrant story

Eley’s promotion to principal is part of some personnel shuffling that will send Principal Natasha Stephenson from Aulander Elementary to West Bertie Elementary. Stephenson is spending some of her time at the conference talking to Eley about the transition, but she’s spending most of her time with Aulander teacher Selesa Johnson-Daniels.

Throughout the conference, when you see Johnson-Daniels, you’ll see Stephenson close behind.

Eight years ago, Johnson-Daniels was in her native Jamaica. She came to Bertie as part of a program through Participate Learning, which helps teachers find jobs in North Carolina and elsewhere as part of a cultural exchange.

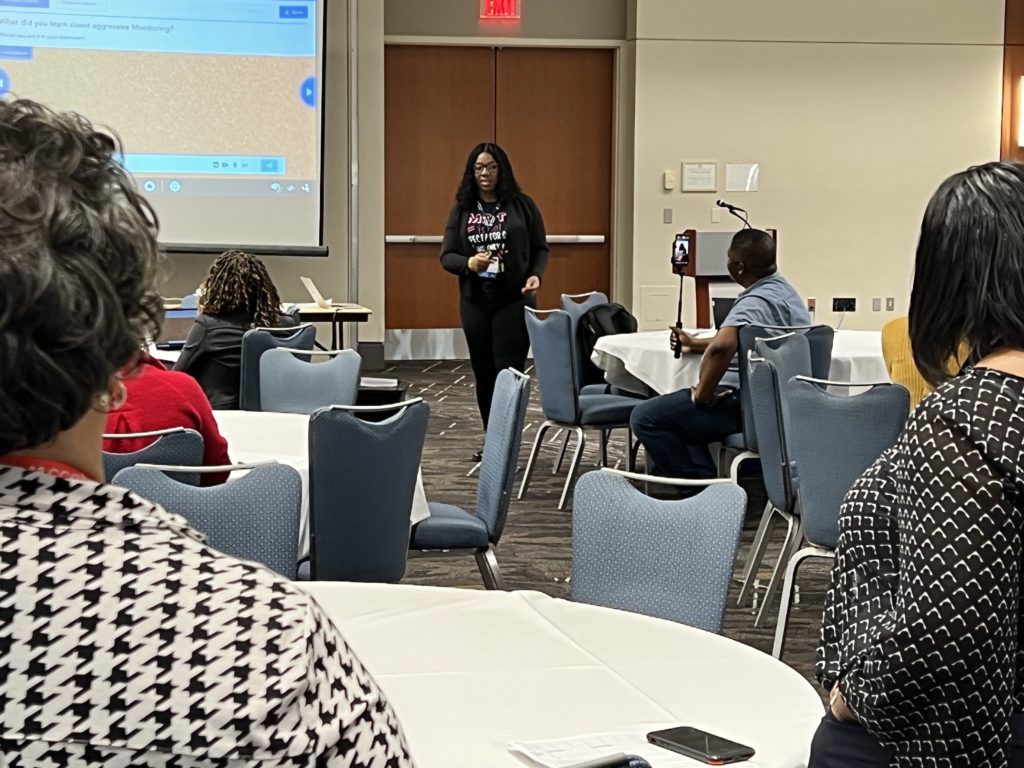

At A.I.M., she’s going to present on how she helped a group of third-graders exceed expectations. She’s nervous — you can see it over the three days she attends sessions, waiting for her turn to speak.

“I’m here to learn, but I’m here to support her, also,” Stephenson says.

That connection with her principal is important to Johnson-Daniels. Connection, itself, is important to her.

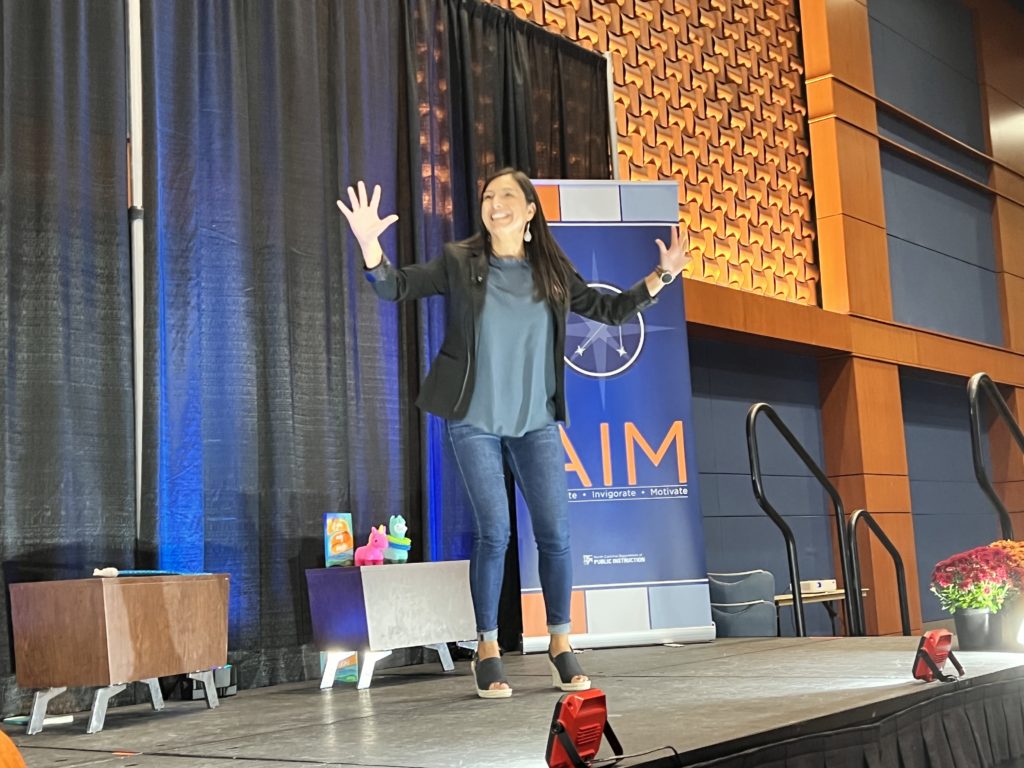

So as she sits at the keynote listening to Emily Francis, she’s having flashbacks.

Francis tells the story of her journey from Guatemala to Cabarrus County, where she’s now a celebrated ESL teacher. The oldest of five kids, in her homeland she took turns with her mother caring for her siblings or going to the open market to sell oranges.

“If I did not sell all my oranges, I would have to go from door to door just knocking — ‘hey, can you buy my oranges?’” Francis said. “I couldn’t come home with oranges. I needed to come home with money.”

Her mother immigrated to the United States without proper documentation to escape poverty, cleaning and doing odd jobs so she could send money home for Francis and her siblings to buy food and clothes. When she earned enough to pay a “smuggler” to bring Francis and her four siblings to the United States, she called Francis and told her it was time to pack the essentials.

Among those were the letters her mother sent while they were apart.

“The letters she would write to me were promises,” Francis said. “She wanted me to become something. She wanted me to become someone.”

But when she got here, Francis says, she lived in linguistic and cultural failure for six years.

“Where do you identify culture, identity, strength so that when I come into your classrooms you can identify these three things?” Francis asks the hundreds sitting before her. She tells them how she found a teacher who named her strengths, and that made a difference.

Johnson-Daniels is hanging on every word. She’s hearing so much of her own journey in Francis’ story. And she’s remembering some of her struggles when she arrived.

She remembers the culture shock. She remembers the students poking fun at her accent. She remembers the parents taking issue with what they perceived as unreasonable demands.

“In the beginning there was a little trouble, because we had to change the expectations,” Stephenson said.

Johnson-Daniels believes in regularly monitoring her students and planning their instruction based on what she learned from the day before. That level of attention to each student comes with a level of demands from them. The parents weren’t accustomed to that.

“But she’s great at building the relationships,” Stephenson said. “She’s strict. She’s stern. The parents weren’t used to that. But once they saw the children moving and growing, they had nothing to argue about.”

Johnson-Daniels took a classroom of kids mostly below proficient in second grade and helped 80% of them achieve proficiency in third grade. That earned her a spot on the conference agenda to talk about daily monitoring reports.

And though she felt some nerves, Francis helped remind her that her voice is important. She brings a different perspective to the classroom, and that perspective warrants notice.

‘It was worth it.’

The conference is wrapping up. There’s only one slate of sessions left in the afternoon — including the one led by Johnson-Daniels. Conference organizer Julie Pittman is on stage giving the last of her thanks. She’s handing out the last of the conference awards, too.

Some attendees are winning awards from call-and-response games. Some are winning prizes for goose chases set up throughout the week. But there’s one surprise.

Bulluck is sitting at a table in the back with her team. She has the contacts she gained in her phone and email, so she knows she has a place to start addressing her SEL concerns. Eley has a smile on her face, readier now to be a principal. Stephenson has a supporting hand on Johnson-Daniels’ shoulder.

Then, from the stage, they hear Pittman talk about a district that has grabbed her attention.

“This district has worked so hard throughout this conference,” Pittman says. “And they have shared and showed up and told stories, and they have networked and made friends, and they have done every single thing that was offered for them.”

As she announces the district’s name and award of five free conference registrations for next year, eight hands shoot straight up in the air.

“I don’t know what I expected,” Bulluck said, thinking back on her mindset coming into the conference. “I knew we were going to learn a lot and meet a lot of people, but I don’t know if I expected all of this.

“It was worth it.”