Share this story

|

|

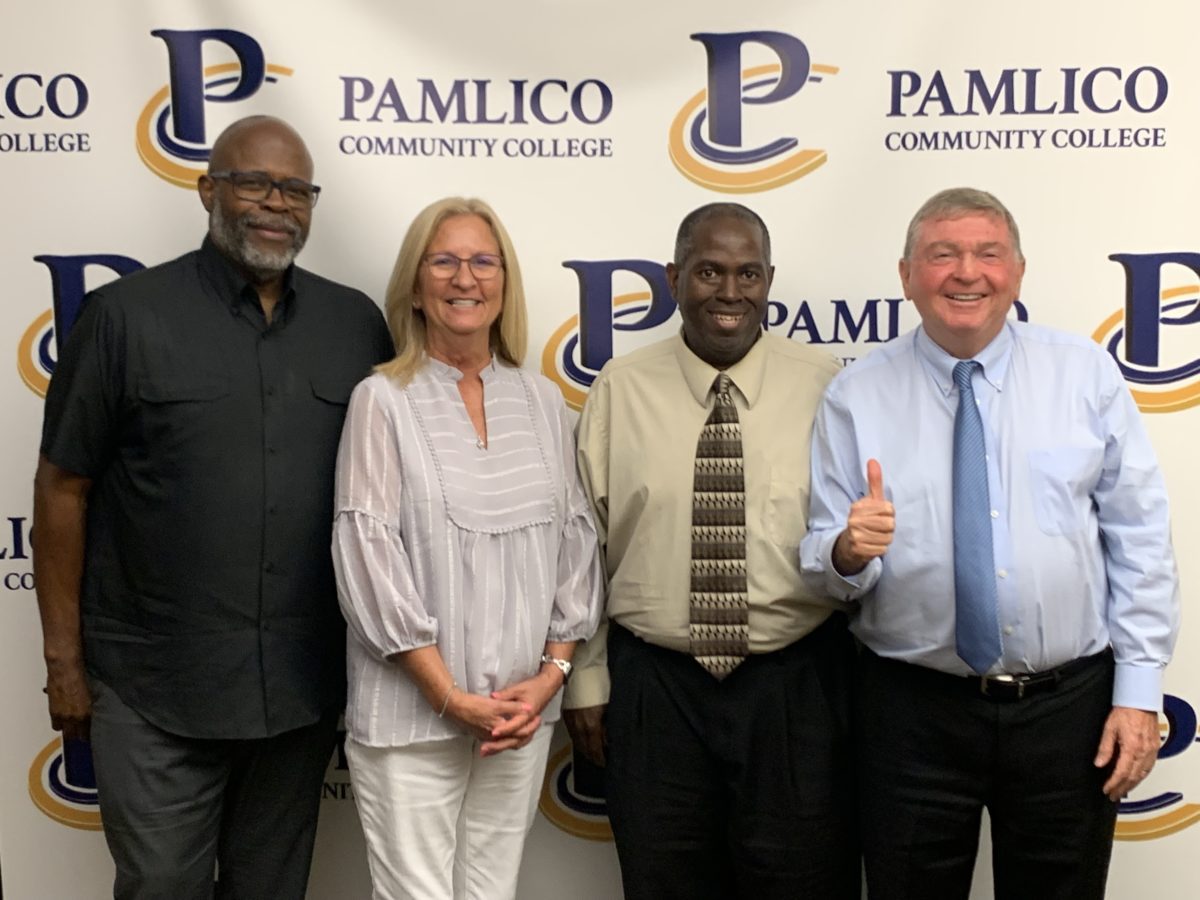

Jim Ross admits that before becoming president of Pamlico Community College (PCC) in 2016, he didn’t think much about people who are incarcerated.

“Like many people, I’d never been in a prison. And I never thought about what happens in prison,” Ross said in an interview with EdNC. “It sounds very cruel on my part and selfish, but it’s very honest that my feeling was just, ‘Keep them away from me, keep me safe. I don’t care what happens.’”

That changed during his second day on the job when Michelle Willis, vice president of instruction, invited him to visit the college’s education program at Pamlico Correctional Institution (PCI).

“Our previous administrations did not feel [the program] was a priority,” Willis said. “So I was talking to him about it and I said, ‘I really would like to go to the prison.’ And he went, ‘OK! You ready?’”

Willis hustled Ross into her car as she frantically made arrangements with the prison for them to visit. The moment turned out to be life-changing.

“When I went out that day, it was like my eyes were open to a world that I didn’t know existed,” Ross said. “These [men] are human beings, too. They could be our brothers. They could be our fathers. They could be our sons, our cousins.”

“These are human beings who deserve second chances, third chances, fourth chances, fifth chances — whatever you have to do.”

Jim Ross, president of Pamlico Community College

That visit turned Ross into an advocate for the educational rights of people incarcerated in Pamlico County.

“I’ve really felt that a calling of mine since then has been to do everything within our power to help those who are in prison to have a chance at a good life when they get out, and not to be forgotten,” Ross said. “These are human beings who deserve second chances, third chances, fourth chances, fifth chances — whatever you have to do.”

‘When Dr. Ross has a vision, believe it!’

Ross threw himself into learning everything he could about the role of postsecondary education in the lives of incarcerated people. He also started talking to anyone who would listen about the program’s potential.

One of those listeners was Sen. Norman Sanderson, R-Carteret, Craven, and Pamlico.

“I said, ‘Listen, I would like us to consider working together to do something bold and dramatic to help the prisoners,’” Ross recalled. “He said, ‘I’m with you. What do you have in mind?’”

Knowing he had the senator’s support, Ross solicited input from the instructors and students at the prison. Based on their feedback, he and his team developed a new program they called Human Service Technology (HST).

“The premise of it was to provide semester-long courses in areas that would provide life skills that [the students] needed to succeed after they got out,” Ross explained. “Those life skills would include communications, would include staying off drugs, would include teamwork, would include being a good father, a good spouse. And one of the real important ones — anger management.”

For decades, PCC had partnered with PCI to provide access to more traditional courses in trades such as carpentry and electrical work.

In Ross’s vision, that work would continue, but HST would be an entirely new program with credit-bearing classes that could lead to an associate degree. It would also include a liaison that would help connect students with employers post-incarceration.

While Willis worked with the community college system to make that vision come to life, Ross drafted a white paper Sanderson could share with fellow legislators to round up support for funding.

Ross relied heavily on decades of evidence that indicate programs like these are among the most effective ways to reduce the likelihood that incarcerated individuals will return to jail or prison after completing their sentences. According to the Vera Institute of Justice:

Few evidence-based reforms have as much untapped potential as postsecondary education in prison. Incarcerated people who participate in such programs are 48 percent less likely to recidivate than those who do not. The odds of recidivism decrease as incarcerated people achieve higher levels of education. These findings are based on a comprehensive study recently updated by the RAND Corporation, which analyzed rigorous research published from 1980 through 2017.

With Ross’s white paper in hand, Sanderson helped PCC secure $650,000 in annual recurring funding starting in the 2017-2018 school year. Willis and her team had about one month to hire new staff and finish developing the program’s curriculum.

“I learned a big lesson,” Willis said. “When Dr. Ross has a vision, believe it!”

Today, PCC’s prison program — now including HST — makes up about one-third of the college’s curriculum.

Preparing students for a ‘new season’

Ed King, one of two department chairs for PCC’s prison programs, has been working with incarcerated students for more than a decade.

King said he knows that some people don’t see the value of programs like the one he leads. He describes himself as a mild-mannered guy, but he got upset when someone once told him they didn’t understand why incarcerated people should get a free education.

“I sort of understand [that] point of view,” King said, “but you’ve got to look at it like this — would you rather pay for their education up front so that when they get out they’re a productive member of society? Or would you rather them climb out your front window with your flat screen?”

Classes in subjects such as masonry, horticulture, and plumbing set students on a path toward family-sustaining wages when they reenter the workforce.

King describes the benefits of the program as twofold: “Not only does it help with recidivism, also it’s a proven fact that when somebody goes to college, their kids are more likely to go to college.”

King’s co-chair of prison programs is Ronald Scott, who was hired to lead HST in 2017.

When Willis saw Scott’s application for the job, she realized they had graduated from New Bern High School in Craven County just one year apart. She now keeps her senior yearbook in her office.

“Mr. Scott had a big afro, he was tall and skinny, and back then the basketball shorts were really short,” Willis teased Scott during their meeting with EdNC.

All joking aside, Scott said he is grateful for the opportunity to do work that he’s passionate about, though he doesn’t think of it as work at all.

“I don’t go to work — I go to life,” Scott said. “This is life for me.”

Sign up for Awake58, our newsletter on all things community college.

Scott described his first day of teaching an HST course. He had a student who had been incarcerated a long time, and when Scott used the prefix “Mr.” to call on him in class, the student was overwhelmed by his emotions. He’d become accustomed to being referred to as “Inmate.”

Scott told his student, “This is a new season right here. This is a new season.”

Measuring impact

It can be hard to know how incarcerated students factor into the college’s economic impact.

In spring 2022, EMSI (now Lightcast) published economic impact reports for all 58 community colleges. Pamlico’s report showed that the college has an overall annual economic impact of $38.2 million. For every dollar invested in PCC, students gain $2.80 in lifetime earnings, taxpayers gain $1.50 in added tax revenue and public sector savings, and society gains $4.90 in added state revenue and social savings.

There are many challenges in tracking specific economic outcomes for incarcerated students. One has been the COVID-19 pandemic, which Willis said had halted her team’s plan to measure the programs’ impact.

Another challenge has to do with how the North Carolina Department of Public Safety operates. Some students at PCI are from other parts of the state and have been transferred to Pamlico County. Similarly, Pamlico residents who find themselves behind bars may not serve their time at PCI.

Without knowing where all of their students end up, it’s difficult to know how they’re using their education when they complete their sentences.

But many students have told Scott that they use their newfound skills to help them cope with the experience of being incarcerated.

“Some of them don’t [get sent to solitary confinement] because they know how to de-escalate a situation because of what they learned in the conflict resolution course we teach,” Scott said. “They’ve got a tool belt that equips them right now, not just when they get out.”

Sign up for the EdDaily to start each weekday with the top education news.

Other students stay in touch after they re-enter society.

Scott bragged about a graduate who started his own trucking dispatch company in North Carolina.

“He hired his first employee last week! He was so excited,” Scott said. “He’s looking forward to hiring another one.”

Dreaming of the future

Ross has plans to expand his college’s program at the prison.

“We have a vision and a prayer that we’d be able to get funding at some point to [build] an education wing, a wing devoted to education,” Ross said.

He explained that there are about 500 people incarcerated at PCI and that PCC has the capacity to serve only about half that number.

“Our dream is for an expansion, so that 250 of the prisoners don’t have to be denied education,” Ross said.

Given what Ross and his team have accomplished so far, there’s no reason to think that dream won’t become a reality.

Ross attributes that success to putting the needs of students first, regardless of their circumstances.

“I found that if you are thinking about goals and helping people, if you’re sincerely doing that,” Ross said, “then there’s nothing you can’t accomplish.”

Recommended reading