Share this story

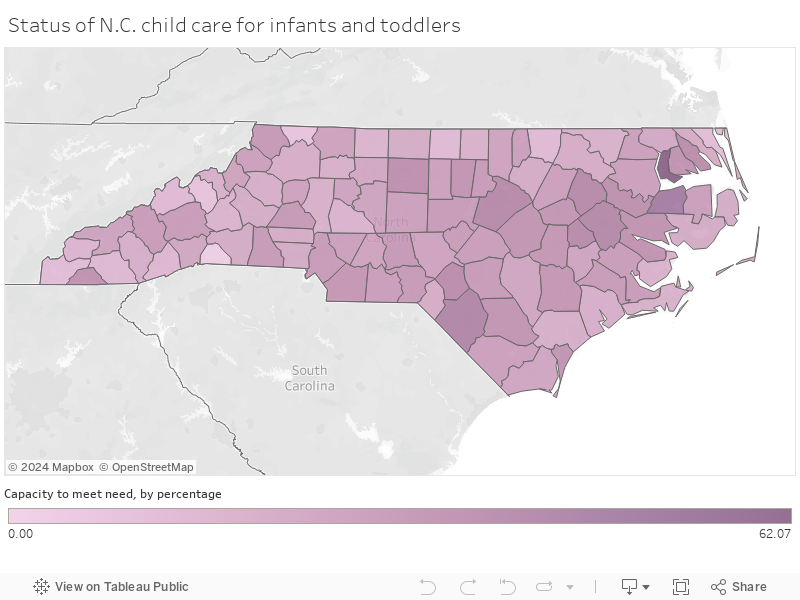

- Child care capacity for infants and toddlers varies greatly by county — from Polk, with no care available, to Chowan, with space for 62% of young children with working parents. Explore your county’s status here. #nced

- "We have to do something before that money runs out," said @NCEarlyEdCo's Elaine Zuckerman of the cliff #childcare is approaching when relief funds expire in 2023. #nced

|

|

North Carolina child care providers have the space to reach only about a quarter of infants and toddlers with working parents, a report released this week shows.

This supply of infant/toddler care compared with the need (or the number of infants and toddlers with working parents) also varies greatly by county. You can explore the map below to see for yourself.

Child care for infants and toddlers is provided during a critical time in their development, and it has unique challenges. Although all care and education before kindergarten has issues of access and affordability, infant and toddler care is especially unavailable and expensive. The median monthly price for full-time infant care in a licensed center in North Carolina is $883 — with a range of $368 to $2,433, the report found.

The state’s child care network has shrunk in recent years, partly due to pandemic issues, with the number of centers serving the youngest children falling from 2,787 in 2016 to 2,123 in 2021, and the number of home-based programs falling from 1,723 in 2016 to 1,015 last year.

The first three years of life also happen to be the most critical in terms of brain development. Research shows secure relationships with caregivers is critical for children’s confidence exploring their environments. Plus, parents need access to child care in order to work and to further their education.

The current model doesn’t meet this multi-generational need, said Elaine Zuckerman, communications manager for the NC Early Education Coalition, which commissioned this report from researchers at the Child Care Services Association.

“We have to do something before that money runs out,” Zuckerman said of the stabilization grants that are providing temporary federal dollars to programs to compensate for the pandemic’s effects.

Some map takeaways

The capacity represented by the shades of purple on the map above is based on two numbers: an estimated number of infants and toddlers with working parents in the county, and the number of spaces for infants and toddlers that child care centers and family child care homes are licensed and willing to serve (also known as the “desired capacity”).

The statewide desired capacity of infants and toddlers in licensed programs is 63,125 — or about 18% of all infants and toddlers and 27% of infants and toddlers with working parents. The unmet need is the greatest in rural parts of the state (there’s space for 16% of all infants and toddlers and 24% of those with working parents).

Some counties are outliers. Polk is the only county with no infant or toddler spaces available. Alleghany and Yancey also have low capacity to reach infants and toddlers, with space for 5% and 6% of those with working parents, respectively.

The counties with the most capacity to meet their infant/toddler care needs are Chowan (with space for 62% of young children with working parents), Washington at 47% and Robeson at 41%.

So why can’t providers open more spaces?

The No. 1 barrier to increasing capacity mentioned in surveys and focus groups was staffing shortages. The pandemic and the overall labor shortage have made an already hard situation worse, Zuckerman said.

This likely explains some of the vacancy rates, she said — which you can also find by county in the map above. Although programs might be licensed and have the space for more infants and toddlers, they often can’t find teachers or make the finances work.

That’s because providing infant and toddler care is extremely expensive. Caring for our youngest children takes more people than caring for older, more independent children. Anywhere from 65% to 80% of programs’ budgets are salaries, the report says. Below, you can see how many more employees are needed for younger children.

| Age of Children | Staff:children ratio | Maximum group size |

| 0-12 months | 1:5 | 10 |

| 1-2 years | 1:6 | 12 |

| 2-3 years | 1:10 | 20 |

| 3-4 years | 1:15 | 25 |

| 4 to 5 years | 1:20 | 25 |

| 5 years & older | 1:25 | 25 |

Most parents can’t afford the true cost of high-quality infant/toddler care. That leaves directors setting prices lower than the true cost and unable to raise wages.

The report found the median starting wage was $12 an hour for infant/toddler teachers in child care centers, with variation across the state: $10 in programs in rural areas, $12 in programs in suburbia, and $14 in programs in urban areas.

As Zuckerman explained, programs need sustainable support — before those dollars run out next summer.

What kind of support is needed?

Another distinction of the infant/toddler space is that there is less public funding than for pre-K — and far less than for K-12. The main source of public funds runs through the child care subsidy program, but that’s based on the rates that providers set rather than the true cost.

Access to this subsidy funding is unequal across the state. Programs in low-income areas end up with fewer public dollars, which is reflected in teacher pay and the quality children and families experience.

Public investments are supported by taxpayers, the report says, citing a 2021 national poll from Children’s Funding Accelerator and FM3 Research that found 70% of voters are willing to have their taxes raised by $25 annually and 64% are willing to pay an extra $150 per year in taxes to increase funding for early childhood opportunities in their communities.

The latest report calls for a program similar to NC Pre-K for infant/toddler care in order for children across the state to have access to quality care.

“Original funding formulas for NC Pre-K helped increase the quality of spaces for preschoolers because the payment rate was tied to a modeled estimated of what it costs to deliver this high quality,” it says. “A similar infusion of dollars needs to be available to ensure that infants and toddlers living in low-income families have access to the very best care.”

What else would help? The report lifts up these changes:

- Higher and expanded tax credits: Raising the Federal Child and Dependent Care Tax Credit from $4,000 to $8,000, reinstating the expanded child tax credit that expired in 2021 under the American Rescue Plan, and bringing back the earned income tax credit, which was ended in 2014.

- Shifting subsidy to cover the true cost of care and maintaining three separate waiting lists by age so more of the youngest children can be served.

- Support from higher education and expanding eligibility for the T.E.A.C.H. scholarship program for early childhood teachers.

- Scaling pilots that work, including the Babies First NC project, which is working to raise the quality of infant and toddler care.

- More financial support and professional development for family child care providers.

- Expansion grants and incentives for centers.

- Further study as the landscape shifts.