Share this story

- When students are grieving the death of a caregiver, the counselors and social workers of @JCPS_NC have a distinctive way of surrounding them in love and support. #nced

- During the first weeks of school last fall, eight South Johnston High School students experienced the death of a parent. Here’s how school counselors and social workers supported them. #nced

|

|

Behind the Story

In January, EdNC reported that evidence suggests at least 3,600 children in North Carolina have experienced the death of a caregiver due to COVID-19. Experts now put that estimate as high as 5,800. In February we distributed a survey to principals, school counselors, and EdWeekly newsletter subscribers asking how they and their communities support grieving children. This story highlights one example.

During the first weeks of school in the fall of 2021, eight South Johnston High School students experienced the death of a parent.

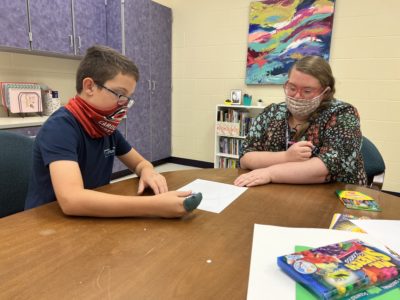

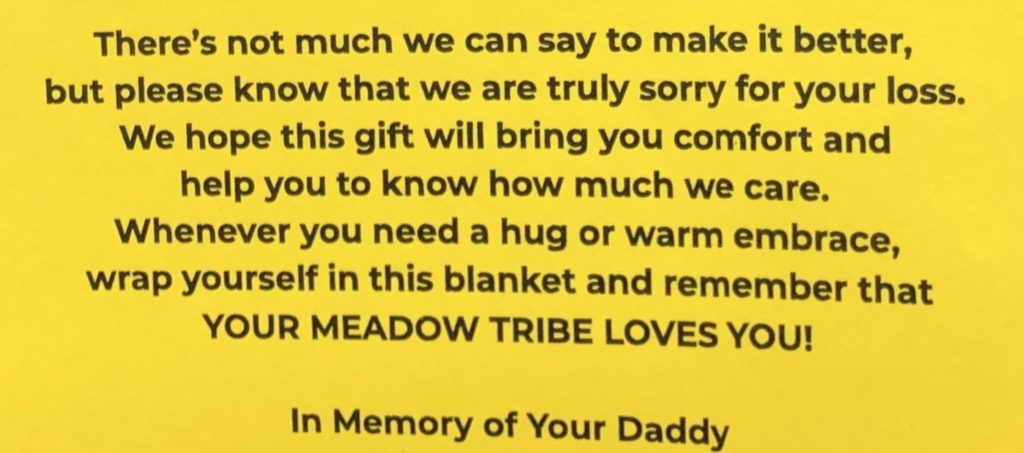

Susan Kelly, coordinator of school social work services for Johnston County Public Schools (JCPS), was responsible for managing the district’s support for these grieving students. One way she typically does this is by delivering custom-embroidered blankets to students at their homes.

This year, the scale of parent deaths presented a new challenge.

“We ran out,” Kelly said in an interview with EdNC. “We had to give sweatshirts for a while because we didn’t have enough blankets.”

Most of the parent deaths in those early weeks of the school year were related to COVID-19.

Across the state, as many as 5,800 children are now considered “COVID orphans” due to the COVID-19-associated death of a caregiver. Communities and schools everywhere have found various ways to support grieving students, but the JCPS approach is distinctive — and meaningful.

Kelly described delivering a blanket to a student this school year, then learning that after she left, the student wrapped himself in the blanket for several hours. “That’s what we want,” she said.

Kelly said she thinks the reason the blankets can make such a difference is because they’re always present. Even when the student is away from their school support system, or has to move in with new family members after a caregiver’s death, the blanket is a tangible and lasting reminder that they are loved and supported.

Like other experts in her field, Kelly thinks about the potential long-term effects the death of a parent can have on children.

They can be at higher risk of failing classes or missing school, she said, even if they were “straight-A kids” with perfect attendance before. Sometimes students don’t identify a caregiver’s death as the reason they’re struggling. “But we do,” Kelly said.

Before the pandemic, fewer students were coping with the shock of losing a caregiver. “Now there’s just so many,” Kelly said.

Adapting to ‘devastating’ resource limits

And while the number of students in need of counseling services has increased since 2020, the number of school counselors available to support them has decreased. JCPS currently has nine unfilled school counselor positions.

Brandy Peters, a school counselor at South Johnston High School, said one of her children attends Benson Elementary, which has been without a counselor since before Christmas.

“It’s just been devastating,” Peters said.

“This year we have felt like we’ve been in crisis mode nonstop.”

Brandy Peters, South Johnston High School counselor

A single school social worker in Johnston County is typically assigned to three or four schools, Kelly said. That presents problems.

“You can’t build relationships, you really can’t meet needs,” Kelly explained. “You’re just trying to put Band-Aids on, and it’s not a good feeling.”

Peters echoed that sentiment on behalf of the counseling and students services department at South Johnston High: “This year we have felt like we’ve been in crisis mode nonstop.”

To ease the strain, JCPS is developing a co-located school-based mental health service, scheduled to launch later this year.

The goal of the service is to have mental health practitioners from the community located on school campuses, giving students and families more convenient access to mental health services. These practitioners would work closely with school counselors and social workers.

Similar programs already exist in nearby Lee and Harnett counties.

Helping students cope in other ways

Individual staff members at schools are also taking action. Carmen White, a school counselor at McGee’s Crossroads Elementary in Angier, led a six-week grief group for students at her school this year.

Community resources are available as well. Kelly and Peters refer students to a bereavement camp sponsored by Johnston Health, a health care provider system affiliated with UNC Health, during the summers.

Camp Courage is a daylong camp for kids ages 6 to 17 who have experienced the death of someone they love. Through activities with peers, along with support from trained staff and volunteers, participants have the opportunity to learn and practice healthy grieving in a safe environment.

But Kelly argues that schools have a special responsibility to provide support for students’ mental health, and she wishes state leaders would provide funding for additional school counselors and social workers.

“Mental health is a very important component of education,” Kelly said. “It doesn’t replace education — ever — but if mental health is not in a good place, then students are not learning well either.”

Peters provided timely examples. “With Mother’s Day and Father’s Day coming up, that’s going to be a trigger for some of our students,” she said. “I have a senior who lost their father, so graduation is going to be another big trigger.”

It’s in those moments when the school counseling team in Johnston County hopes students will wrap themselves in a blanket of love.