|

|

Highlights

- North Carolina is planning to hire an outside group to study its child care subsidy model.

- The work could establish new ways to fund subsidized care, including higher pay for early childhood teachers.

- Subsidized care is based on what parents can afford, which does not cover the true cost of high-quality care.

- New Mexico, Louisiana, and Washington, D.C., can serve as examples.

The state Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS) is looking to hire an outside consultant to research new ways to structure its child care subsidy program.

The way the program works now bakes inequities and instability into the state’s child care infrastructure, researchers and advocates say.

That’s because the current subsidy model is based on what families can afford. Although child care is expensive, its prices are still not high enough to cover the cost of high-quality care and learning, including living wages for early childhood teachers.

This research could be a first step in understanding how the subsidy program can support a more stable system for children and families. The state has released a “request for proposal” for an outside consultant, according to DHHS.

“North Carolina’s Child Care Subsidy program is another tool to support high quality, accessible child care that keeps our economy moving,” said Kelly Haight, a DHHS spokesperson, in an email. “Subsidy rates that are tied to tuition and market rates often understate the true cost of providing high quality child care, especially for infants and toddlers. Studying alternative models for subsidy rates will help us understand if new calculation methods could better reward quality child care, promote stability in programs across the state and ensure access for families.”

Why is child care not subsidized at its true cost?

Right now, the amount of money provided through the subsidy program for each child is set through a market rate survey. States ask providers what they charge parents and use that information to set subsidy rates. Federal policy says that states should set rates at least at the 75th percentile of prices, meaning that families using subsidized care should be able to access most options.

But again, those rates do not reflect the true cost of high-quality care and learning.

The mismatch between the price and the cost is often referred to as a market failure. Child care prices are too high for many families but not high enough to pay living wages to teachers or meet the needs of children and families.

The result is instability for providers — whether they are charging parents privately or serving children with subsidized care — as well as for teachers, children, families, and workplaces.

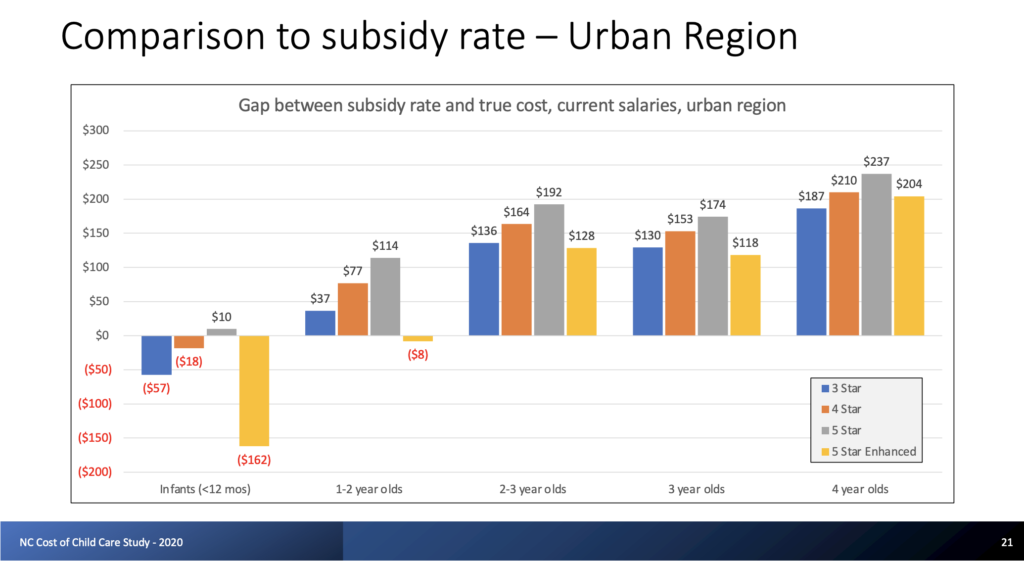

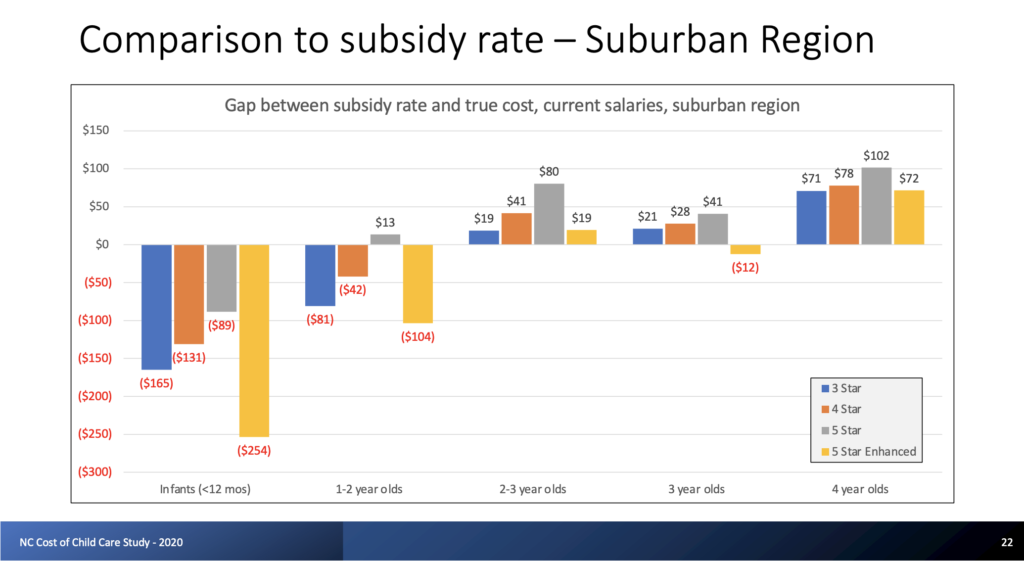

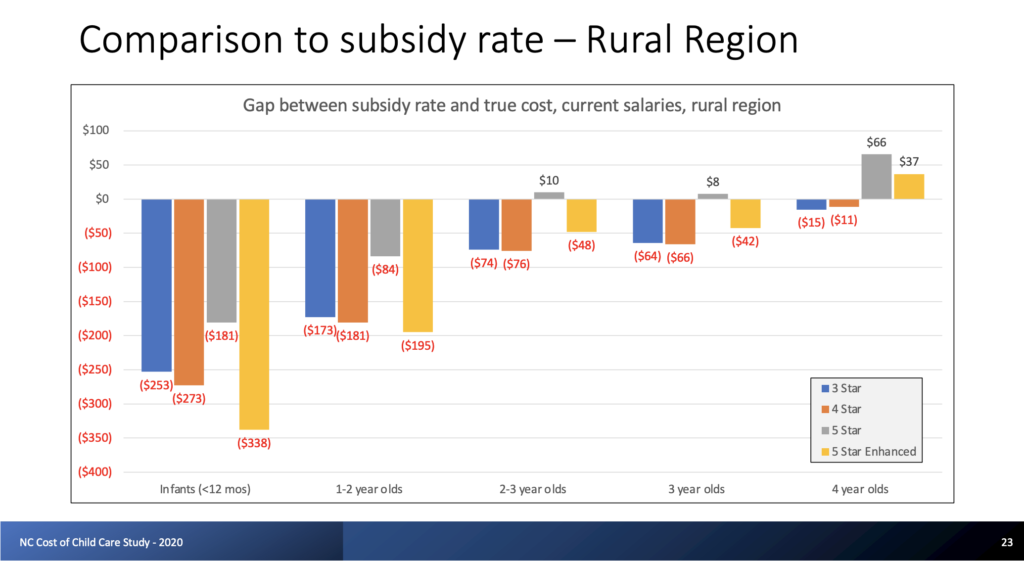

A 2021 Division of Child Development and Early Education study looked at the gap between subsidy rates and the true cost across geographic areas, age ranges, and quality levels, finding infant and toddler care and rural areas had the most dramatic gaps. The state paid the Center for American Progress to conduct that study, with additional resources from the National Collaborative for Infants and Toddlers.

These challenges existed before the pandemic, but they have been exacerbated since, Haight said.

“The pandemic further stressed child care, shining a bright light on long-standing challenges related to the cost of providing care, the low wages of child care professionals and the ability of families to afford care,” Haight said.

The current model also means providers in low-income areas receive less in subsidy dollars.

“Those providers who have the least resources, they get the least in public funding as well,” said Simon Workman on a recent Hunt Institute webinar. Workman is principal and cofounder of Prenatal to Five Fiscal Strategies, which New Mexico contracted for its work, and a lead author of the North Carolina study.

North Carolina’s subsidy system, which was serving 54,271 children in November, is funded with a mix of state and federal funds.

A law in 2014 made it possible for states to study alternative methodologies for their subsidy funding structures. Researching the rate calculation is just one step. Funding would be needed to pay those higher rates — while also reaching more children and families.

“We all want to do the best for kids,” Workman said. “But at the end of the day, that is a question about money, and how much money there is to do this.”

So has any other state tried this?

Two states and one city have calculated the true cost of care since 2014 and have committed to paying providers that cost through their subsidy programs: New Mexico, Louisiana, and Washington, D.C.

Elizabeth Groginsky, cabinet secretary of New Mexico’s early childhood education and care department, originally made this change while serving as Washington’s assistant superintendent of early learning. Last year, New Mexico made the shift after a two-year cost modeling process. The state’s subsidy rates now cover the full cost of care for home-based providers and more than 90% of the cost of care for child care centers.

The state used recurring state and federal dollars to increase the rates. It also expanded eligibility with nonrecurring relief funds, said Micah McCoy, the department’s communications director.

“We have to get serious about no longer just funding our prenatal-to-five programs, and our child care in particular, based on whatever’s available, but actually on what it costs to deliver the quality care,” Groginsky said on the same Hunt Institute webinar.

Sign up for Early Bird, our newsletter on all things early childhood.

This work required looking at the entire system, Groginsky said: what drives cost, what matters in terms of quality, what revenue streams are available, and what different providers need.

“You have to look at your licensing regulations and see what is expected of a child care provider in your state,” Groginsky said. “If they’re really doing it, and they’re making sure they’re meeting all the regulations, what will that cost them? Now you bring in your quality rating improvement system. What are you asking providers to do to raise up to three, four, or five star? What are the cost drivers in there? And so it’s a great opportunity. And the other part about it is that you you don’t do it in isolation.”

She said ensuring providers and other stakeholders were a part of the process was critical. The result was not only a change in the state’s current subsidy rates, but a tool to move forward.

Jeanna Capito, who was also on the webinar and is another cofounder of Prenatal to Five Fiscal Strategies, said the tool is meant to guide further quality improvements, such as providing higher compensation and benefits. Asking providers about their goals is also important, Capito said.

“That’s always something that folks get a little bit concerned about is like, don’t ask me what I currently pay people, I don’t want to keep paying them that,” she said. “We harness that as part of this process. And that’s why we talk about it being not just this point in time, but this long game that a state is engaging in to do things differently, and that it’s going to take time to make all the changes to do things differently. But providers have to be partners in it at every step of the process.”

Recommended reading