Update October 22, 2021, 3:48 p.m.: The order from Monday’s hearing was entered today. It is at the bottom of this article.

The judge in the long-standing Leandro case is ready to act.

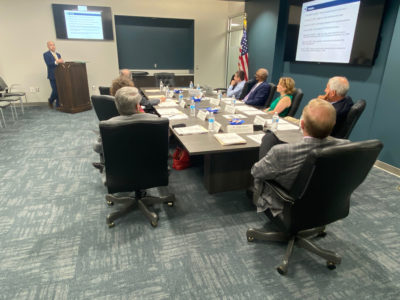

In a hearing Monday, Judge David Lee gave the parties in the case until Nov. 8 to submit their suggestions to an order he may enter to address whether the legislature is providing the funding necessary to implement a plan to ensure the state’s students have the opportunity for a sound basic education.

Lee gave the plaintiffs until Nov. 1 to submit their suggestions. The defendants will have another week after that to respond. He said he is not willing to wait for legislative Republicans and Gov. Roy Cooper to hammer out a budget agreement that may or may not fund the Leandro plan.

“I think everyone knows I’m ready to pull out of the station and see what is around the next bend,” he said, adding later: “I’m not going to beat myself up further about our state adopting a budget … I’ve dealt with that … as long as I think I reasonably can.”

The Supreme Court of North Carolina, in its landmark Leandro v. State of North Carolina decision over two decades ago, held every child has a state constitutional right to access to a sound basic education. The courts also found that North Carolina was not meeting this constitutional requirement.

Since then, courts and parties involved have been trying to make this right — most recently with the comprehensive plan signed and ordered by Lee in June.

The parties last met in September when Lee gave the General Assembly until Monday to fund the plan or else he said he would be ready to act. Much of Monday’s hearing was taken up with plaintiffs’ attorneys speaking to Lee about possible avenues of action.

Sign up for the EdWeekly, a Friday roundup of the most important education news of the week.

Plaintiff’s attorney Melanie Dubis presented on Lee’s possible options, but started by reminding the court what she said previous Leandro Judge Howard Manning used to say.

“I would like to remember what this case is about. This case is not about anyone in this room … (Manning) would often remind us that this case is not about the adults,” she said. “The case is about children.”

She said that 17 years, 2 months, and 18 days have passed since the state Supreme Court ordered the state to remedy its violation of the constitutional right to the opportunity for a sound basic education for all children.

Dubis argued the authority that Lee has to act, citing a variety of sources for such authority including two previous state Supreme Court rulings in the Leandro case. In the original 1997 ruling, she said the state’s highest court stated that the judiciary must give “reasonable deference” to the legislative and executive branches.

“We submit your honor that we have checked that box,” she said, reiterating that deference has been paid to both branches of the government for 17 years.

She also said that the plaintiffs in the case, as well as the governor’s office, have now come up with a plan to correct the state’s constitutional insufficiencies and that the Supreme Court ordered in 2004 that if the state does not abide by its constitutional responsibilities, the courts can act to correct the issue.

She said one option is that the court can order a writ of mandamus. The Legal Information Institute at Cornell Law School gives the following overview:

“According to the U.S. Attorney Office, ‘Mandamus is an extraordinary remedy, which should only be used in exceptional circumstances of peculiar emergency or public importance.’”

Dubis said this is a rare action but one that is reasonable in this current case. Another rare circumstance in which such action has been taken was with court-ordered desegregation, she said.

Related reading

She said an injunction was another option. The Legal Information Institute describes an injunction as “a court order requiring an individual to do or omit doing a specific action. It is an extraordinary remedy that courts utilize in special cases to alter or maintain the status quo, depending on the circumstances …”

Dubis mentioned that the courts have used injunctions before in the Leandro case. In 2011, Manning ordered that North Carolina could not limit the percentage of students who could be served by a statewide pre-K program. According to Dubis, that order was appealed by the legislature all the way to the state Supreme Court, but ultimately lawmakers reversed their move before the Supreme Court acted.

“There is a remedy available here. There is a remedy that is grounded in the state constitution, in the state constitutional authority granted to the court,” Dubis said. “There is not a separation of powers issue at play here.”

She went on to say: “Anyone who argues … that the court does not have the authority is arguing that our state constitution is not worth the paper it’s printed on.”

Lee heard other options as well, including sanctions, and he heard about similar education cases in Kansas and Washington. In 2004, for instance, the courts ordered Kansas schools closed until lawmakers addressed the unconstitutional finance system in effect. Lee said he had no interest in shutting down schools in North Carolina.

Lee also addressed arguments by some that Republican lawmakers weren’t consulted before a comprehensive plan was developed in the case. He pointed out a state law created by the General Assembly in 2017 that would have allowed lawmakers to participate.

“Any action in any North Carolina State court in which the validity or constitutionality of an act of the General Assembly or a provision of the North Carolina Constitution is challenged, the General Assembly, jointly through the Speaker of the House of Representatives and the President Pro Tempore of the Senate, constitutes the legislative branch of the State of North Carolina and the Governor constitutes the executive branch of the State of North Carolina, and when the State of North Carolina is named as a defendant in such cases, both the General Assembly and the Governor constitute the State of North Carolina,” the law states.

“They have always been included,” Lee said.

Sign up for the EdDaily to start each weekday with the top education news.

Meanwhile, as the hearing kicked off Monday, the office of Senate President Pro Tempore Phil Berger, R-Rockingham, issued a press release that criticized “Leandro complainers” for using what the press release called “years-old data.”

During the hearing, Berger spokesperson Pat Ryan wondered in an email whether anyone would bring up the following Supreme Court precedent that puts funding responsibility in the hands of lawmakers (bolding added by Ryan):

“The appropriations clause of the North Carolina State Constitution provides that ‘[n]o money shall be drawn from the State treasury but in consequence of appropriations made by law, and an accurate account of the receipts and expenditures of State funds shall be published annually.’ N.C.Const. art. V, § 7(1). In light of this constitutional provision, ‘[t]he power of the purse is the exclusive prerogative of the General Assembly,’ with the origin of the appropriations clause dating back to the time that the original state constitution was ratified in 1776.”

After the hearing, Berger’s office released another press release, criticizing Lee’s interest in the Kansas case that closed schools and questioning his authority to act.

“This is yet another example of why the founders were right to divide power among the branches of government, giving power to create law and spend money with the legislature, not an unaccountable and unelected trial judge,” the press release said.

The press release also challenged Lee’s suggestion that lawmakers were always included in the case, saying that the creators of a report that formed the basis for the comprehensive plan at issue in the hearing “excluded the legislature from their closed-door process in developing their multi-billion dollar spending proposal.”

While Lee awaits recommendations from the parties in the Leandro case, the rest of the state waits for lawmakers and Gov. Cooper to deliver a budget.

In his proposed budget, Cooper would fully cover the costs of implementing the second and third year of the comprehensive plan. Meanwhile, the Senate budget proposal includes funding that would cover almost 28% of what is needed to implement the comprehensive plan in 2021-22, while the House proposal would cover about 20%, according to progress reports delivered to the court by the Leandro parties. The plan calls for $690.7 million in 2021-22 and $1.06 billion in 2022-23.

If a budget is passed this year, it will be the first budget enacted by the state since 2018. Cooper vetoed the budget in 2019 and Republican lawmakers failed to override it. The state hasn’t had a new budget since.

Recommended reading