|

|

Celeste Cervantes still remembers, when she was in the fifth grade, coming home with the form to choose her middle school. She already knew how she wanted to fill it out. She wanted to attend a STEM magnet school with her friends.

When her teacher handed her the form, though, it came with instructions to have her parents fill it out.

Dutifully, she took it straight to her mother.

“And she was like, ‘I don’t know anything about that,'” said Cervantes, who was born in Winston-Salem to parents who immigrated from Mexico.

Cervantes’s mother, Guadalupe Pantoja, places great value on education — something she picked up from her own father. She made sure her kids kept up with their homework and went to school every day. But her English wasn’t great back then, and besides, parents didn’t make decisions about where kids went to school back home in Ojo de Agua de la Trinidad. Teachers did.

She handed the form back to her daughter. “I can’t really help you,” she said.

“I didn’t really get the form turned in on time,” Cervantes said. “It’s a lot of responsibility for a 10-year-old to remember that sort of thing. So they just ended up sending me to my [base] school.”

It worked out fine for Cervantes. Her base school was also a magnet. While there, and also in high school, she found several teachers who took an interest in her and guided her. One even pointed her to a college preparation program called Crosby Scholars. It helped push her throughout the remainder of her K-12 schooling, and it guided her and her parents through the college application process.

But Cervantes’s schooling experience is a series of these sorts of happenstances. Her parents weren’t always informed about opportunities, but things worked out anyway. Cervantes is in her final year of college at UNC-Greensboro. Majoring in elementary education, she wants to be a teacher so students like her won’t have to depend on chance.

“For families like mine, if their parents don’t know the education system here, and maybe they only went through middle school where they are from, I want to be that teacher who can help them,” she said. “I want to represent, particularly, Latinx communities, but also underrepresented students in general.”

Cervantes was a speaker this week at the 2021 Latinx Education Summit hosted by LatinxEd. She joined a chorus of educator, student, and family voices in conversation about advancing the Latinx student experience — an especially urgent issue as the Latinx population in North Carolina grows quickly.

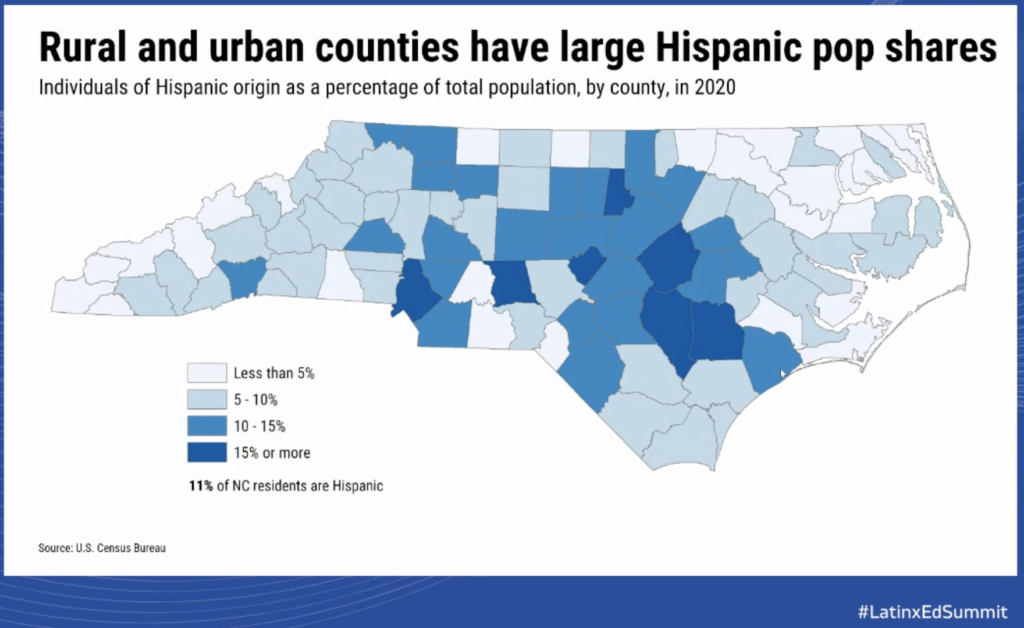

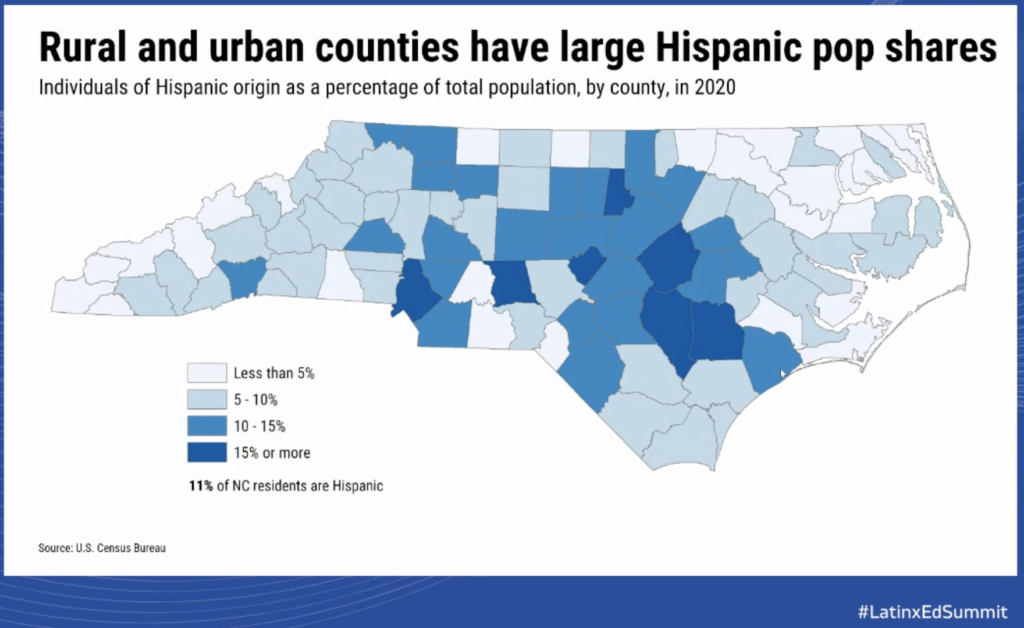

One in six children through age 17 in North Carolina is Hispanic, according to census data presented at the summit by Rebecca Tippett, director of Carolina Demography. That works out to nearly 400,000 Hispanic youth in the state. According to American Community Survey results, 93% of them were born in the United States.

“We dream of a North Carolina where every community and school has a culturally sustaining environment that recognizes, meets, and honors the diverse needs of Latinx immigrant families,” said Elaine Utin, who, along with state Rep. Ricky Hurtado, co-founded LatinxEd and kicked off the summit a day after the organization’s third birthday.

Cervantes launches with a head start, others not so much

Even though Cervantes didn’t attend the STEM magnet she initially had her heart set on, she attended a good school. And she was already identified as academically and intellectually gifted (AIG), securing her a pathway to advanced coursework.

She credits that, in part, to an early start to her education. But she easily might have missed out on that.

In Ojo de Agua, a village in the Mexican state of Guanajuato, school starts in first grade. It runs through the equivalent of middle school. Children study for about nine years, paying for the cost of books and small subscription fees. If they want to study further, they go to the city and pay a tuition.

Cervantes’s parents stopped after their third year of middle school. For her mother, her education almost ended after her first year of middle school, when Pantoja’s father passed away and her mother couldn’t afford the fees. But Pantoja’s grades were so good, the teachers insisted she return — they’d take care of the cost.

When Cervantes was born, her parents just sort of assumed things would go the same way — they’d send Cervantes to school when someone told them it was time. They had never heard of Pre-K or even kindergarten.

“The way the school system works here versus in our country, it is different,” said Celeste’s father, Jose Cervantes. “There was times that they needed help with something, and it was difficult for us to help. Things are taught different here, and it’s just a different world.”

But when Pantoja was pregnant with Cervantes’s younger brother, she had gestational diabetes and made doctor’s visits for a high-risk pregnancy. A social worker came to see Pantoja during those visits and noticed Cervantes.

“She saw Celeste was smart,” Pantoja said. “She said, ‘We have to do something with Celeste.’ So she gave me this application for Pre-K.”

That’s how Cervantes got an early jump on school. She got an early look at something else, too: a lack of support for Spanish-speaking families. One day at Pre-K, Cervantes watched her teacher struggle to communicate with a parent of one of her classmates. At age 4, Cervantes stepped in to translate.

“That’s why she wants to be [a] teacher,” Pantoja said. “She wants to help immigrant families.”

While Cervantes got a head start in pre-K and identified as AIG in elementary school, she recalled different experiences for some of her friends and family. One friend, also born in the United States to immigrant parents, was a native English speaker with little conversational command of Spanish. But he believed the students in the school’s English as a Second Language program did easier work than other kids. So he pretended to speak Spanish and to struggle with English. He lasted in ESL until fifth grade, Cervantes said.

The power of great teachers

In public schools across our state, about 18% of students and only 3% of teachers are Latinx, according to the DRIVE Task Force’s report. It’s why so many Latinx students can go most, or even all, of their K-12 journey without having a teacher that looks like they do.

But that representation is important. Gov. Roy Cooper created the DRIVE Task Force in 2019 to study the issue, and to provide recommendations on diversifying North Carolina’s teacher pipeline. That group, now cited in the Leandro Plan, is working to implement the recommendations.

That mission is shared by Cedar Ridge High School Principal Carlos Ramirez, who also spoke at the LatinxEd Summit. Ramirez, who grew up in California, recalled an advanced history course he was encouraged to take and how he learned about his ancestors’ rich history for the first time.

“I did not realize until I was a junior in high school how my culture was erased,” he said. “How my language … was erased and how we were taught to be less than.”

It angered him, and still lights a fire inside that keeps him engaged in la lucha — the struggle. He holds in his heart, now, a deep pride for his culture and the accomplishments of his people. And he wants Latinx kids growing up to feel pride, too. Sometimes, it happens simply when they see him — the son of poor, Mexican farmworkers who became a teacher and a superintendent, and now leads a school in Orange County.

“It’s just so cool to see when students can make that connection and then they have this belief that if you could do it, then I could do it,” Ramirez said. “The impact that you’ll make is beyond measure. For those of us who have grown up not seeing Latino administrators or Latinos in education — I didn’t see my [first teacher] until high school, and I didn’t see a principal until I became one. It really is so needed.”

Cervantes didn’t have Latinx teachers in her K-12 journey. But she had a lot of great teachers. Teachers who took an interest in her. Teachers who saw talent in her and encouraged her.

One teacher, in particular, encouraged her to enter a poetry competition and supported her desire to write in Spanish. That teacher even introduced her to other Mexican writers, like Gloria Anzaldúa, who bridge English and Spanish.

“Luckily, I was motivated and independent enough about my school,” she said. “I was close enough to my teachers to ask them for help and to look for support and opportunities on my own.”

But she knows the experience wasn’t the same for many of her family and friends. She saw it with her peers growing up, and she hears it at her mom’s small business, which caters to Latinx families. She’s proud of her mother, who has now learned a lot about the public school system and talks to other Latinx parents — especially about college and the Crosby Scholars Community Program, which helps students in public middle and high schools in Forsyth County prepare academically, personally, and financially for college admission and other postsecondary opportunities.

And when Cervantes goes into classrooms now through pre-service assignments, she celebrates her culture with other Latinx students and talks about the opportunities she had.

“I saw that students like me weren’t represented in the people who were working at the schools I was at,” Cervantes said, “and I want to provide that voice for students like me and for students with families like mine.”

It’s a much-needed voice within communities that are poised to become a large share of our citizenry and workforce.

Trouble with the postsecondary pipeline

Tippett said that Hispanics, compared with all students, are less likely to complete high school on time. Even when they do graduate high school, Hispanic students are least likely to report intentions of attending postsecondary schooling. The gaps persist in actual postsecondary enrollment.

“More than half of all North Carolina high school graduates enroll in postsecondary,” Tippett said, but “less than 40% among our Hispanic graduates.” She added that the gaps are widest in the regions that include Raleigh, Durham, and Charlotte — where more employers require postsecondary degrees.

The data also show that once these students enroll in postsecondary programs, they tend to stay in those programs, Tippett said.

“This is really important because when we’re thinking about that postsecondary pipeline, for Latino students the big fall-off is in the transition from high school into postsecondary,” she said. “Once students are in postsecondary, they’re very successful, tend to stay, and they actually graduate at fairly high rates.”

Some of the transition issues, speakers at the summit said, can be attributed to high numbers of aspiring first-generation college students among the Latinx population. Hector Hernandez-Arroyo, a senior at UNC-Greensboro, was one of those. Heading into his senior year, he wasn’t considering college.

His mind started to change as teachers at his school talked about college opportunities and he noticed the difference between work that left people physically tired, like construction jobs, and work that left people mentally tired.

“I would rather be mentally tired,” he said.

Another barrier, Cervantes said, is FAFSA. Many students need financial assistance to attend college, especially in four-year programs. But the FAFSA process was unfamiliar to her parents. She managed with assistance her family received through the Crosby Scholars program.

“About half of North Carolina children and 75% of Hispanic children live in a household where no adult has a postsecondary degree,” Tippett said. “So, this is really challenging because it means that they’re less able to understand how exactly you navigate that pathway because their parents have not also walked that pathway.”

Tippett also pointed to income inequality for the Latinx communities, adding that it’s a cyclical problem that will result in widening income gaps for this community, as well as trouble for the state’s future workforce.

“Right now we’re using race and ethnicity as really crude proxies for social class and social status,” she said. “I think it also is likely what we see is, particularly among low-income students, a real downturn in postsecondary enrollment. Which has really long-term ramifications — not just for our state’s labor force and overall preparedness and ability for us to fill jobs that are being vacated by retiring Baby Boomers, but also for income inequality.”

Ramirez feels that urgency. He feels it for the future prospects of Latinx students, and he feels it for their sense of belonging and their pride of culture and history in the present.

“And I can tell you that all of you who are here,” Ramirez said to panelists and attendees, “you are an advocate, and we need you. If not you, who? And you’re not alone. Hopefully, through our conversations, we can move from a conversation to some tangible, actionable steps because the time is now.”