The most recent data on distressed local governments in North Carolina shows a disturbing trend where counties are showing up as high risk more often than in the past, and the state is having to take a more active role in local government operations.

The state’s local government commission (LGC) — part of the Office of the State Treasurer that was founded in the 1930s — is currently in control of the finances of five local governments in North Carolina. The finances for four of those were taken over in the last 19 months. The LGC has only used its power to take over local government finances 10 times in its history, according to staff at the LGC.

The five local governments whose finances have been taken over are:

- Kingstown in Cleveland County

- Eureka in Wayne County

- Spencer Mountain in Gaston County

- Robersonville in Martin County

- Cliffside Sanitary District in Rutherford County

Additionally, according to the most recent data, seven local governments are considered high risk when it comes to the three areas reviewed annually by the local government commission. Those three areas are:

- Internal control issues

- Financial issues — General fund

- Financial issues — Water/sewer fund

Of the seven local governments that are high risk in all three of these areas, two of them are counties. Staff at the LGC call that fact “unusual and concerning.”

The five municipalities and two counties are:

- Elm City in Wilson County

- Fremont in Wayne County

- Pikeville in Wayne County

- Pilot Mountain in Surry County

- Spring Lake in Cumberland County

- Bertie County

- Edgecombe County

The counties, in particular, are significant when you consider the role of counties in funding public schools. The bulk of the money for the state’s public school systems comes from the state, but counties often bolster their public schools with local funds. Bertie and Edgecombe are both tier one, economically distressed counties.

“County financial issues do affect school funding,” said State Treasurer Dale Folwell. “There is nothing more certifiably true than that.”

This data is the most recent available, but it all stems from June 30, 2019 financial audit data. That means it all predates the COVID-19 pandemic. Folwell said that while this data is not a result of COVID-19, it will be made worse because of it.

What’s happening?

Sharon Edmundson, the deputy treasurer for the state and local government finance division of the North Carolina Department of State Treasurer, said there are several possible explanations for the latest data, including an urban-rural divide.

She said many rural parts of North Carolina are seeing job and population loss as well as drops in tax values.

“Some of these rural areas have never recovered from the loss of tobacco and textiles,” she said in an email.

Additionally, a wave of retirements from experienced government employees is contributing, as is aging infrastructure.

“Many small entities funded the installation of their wastewater systems with federal grant dollars in the 1960s and 1970s and that infrastructure has reached or gone beyond the end of its useful life,” Edmundson said in an email. “It’s also underground, and it’s easier to delay maintenance on something you can’t see.”

Additionally, she said there is less federal grant money available, yet some small local governments still count on such grants for their capital needs.

Folwell said all of this has been years in the making.

“It’s a combination of things that have been happening to rural North Carolina … for the past 20 years, and it’s a huge concern,” he said.

Folwell said that sometimes what’s needed is “watching the pennies and paper clips” to improve the situation. But in other circumstances, the problem is just math.

For instance, he explained the situation of Tyrell County, which is on the unit assistance list and considered high risk when it comes to internal control issues. Back in September of 2019, the state closed its prison in Tyrell County. But the prison was the biggest customer of Tyrell County and the Town of Columbia’s water and sewer system. With the prison closed, the system’s total output dropped by 30% and “shot a hole” in the finances of the county.

“It’s one instance where we were within 24 hours of the county having to default on a loan which would have been the first one since the depression in North Carolina,” Folwell said.

This kind of thing can happen because the population of Tyrell County is so small. Folwell said it’s about equal to the student and faculty population of Myers Park High School in Charlotte.

Shrinking populations are a hallmark of rural North Carolina, and situations like what happened in Tyrell County can happen elsewhere.

What is this data?

The data all comes from the following list, called the Unit Assistance List.

Every year, every local government in the state must submit audits to the local government commission. That includes cities, counties, water and sewer authorities, public hospitals, public libraries, and more.

The places that make the unit assistance list are ones with issues in one or more areas that require state monitoring or assistance of some sort.

When a municipality, county, public library, etc. makes it onto the list, the staff at the local government commission tries to connect with the government in between audits to see how they’re doing and what kind of help they need. The ones with the most severe needs may get assigned to a coach team at the local government commission. Basically the job of the local government commission is to help places get off the list.

There are other consequences that come with being on the list, particularly if a local government is considered high-risk. It may be harder to get approval from the LGC to undertake debt — for example, if a county wanted to take on debt to build or repair public school facilities.

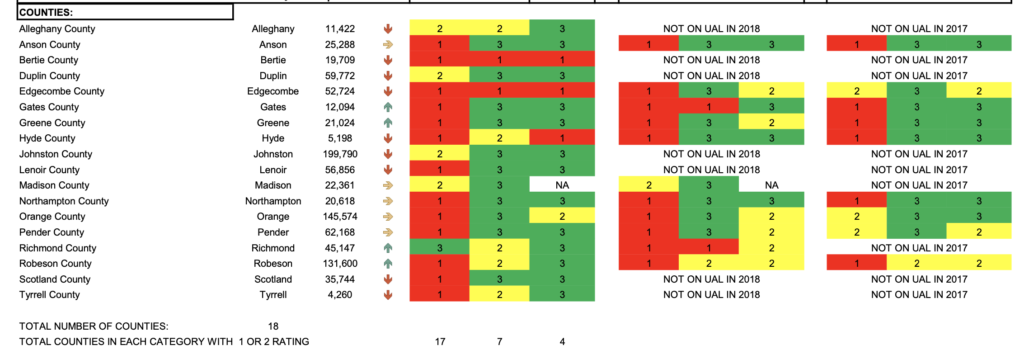

In addition to Bertie and Edgecombe, there are 16 other counties on the list. Other than Bertie and Edgecombe, only one, Hyde County, has more than one area in which it is considered high-risk.

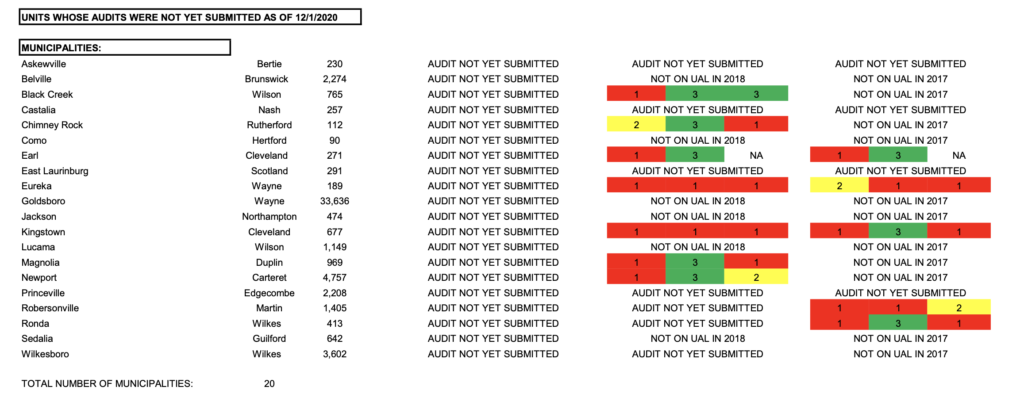

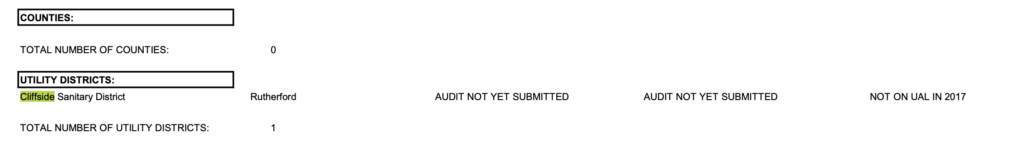

When it comes to the places whose finances have been taken over by the local government commission, none of the five are included in the seven mentioned above that are considered high-risk in all three areas reviewed by the LGC. But that’s not because they’re doing well. In fact, four of the five haven’t even submitted the required audit information for 2019.

They are included on a list of 20 municipalities and one utility district that didn’t submit data for 2019. The fifth, Spencer Mountain, isn’t on the the unit assistance list at all. According to LGC staff, that’s because the General Assembly suspended its charter and, as such, it doesn’t have to submit audits anymore. The same is true of Eureka, which is being removed from the list since it doesn’t have to submit audits while its charter is suspended.

Nevertheless, just being on the unit assistance list and being at risk doesn’t necessarily mean the local government commission is going to take over.

Local government commission staff says conditions set out in this state statute “must be met in order for the LGC to exercise its authority and assume financial control.”

“It is a measure that is taken as a last resort, and not something we ever aspire to do,” LGC staff said in a written response to questions. Staff said that if a local government is “in danger of defaulting on bonded debt or has been unwilling or unable to bring itself into compliance with the Local Government Budget and Fiscal Control Act, they are a candidate for LGC action.”

Counties now and then

Of the 18 counties currently on the unit assistance list, only 11 were on the list the previous year, and only two, Gates County and Richmond County, were considered high risk in more than one area. They were both high risk in 2018 in both internal controls and financial issues general fund. In 2017, only nine counties were one the list, and none were high risk in more than one area.

As for Bertie and Edgecombe, in 2017 and 2018, Bertie wasn’t even on the list. Edgecombe was considered high risk for internal controls in 2018 and wasn’t high risk for any category in 2017.

With the long session of the General Assembly underway, Folwell said that lawmakers should be thinking about issues raised by the unit assistance list, particularly when it comes to rural North Carolina.

“I think what they should be thinking about is the fact that we all appreciate having a strong torso, but it’s very helpful to have strong legs and arms,” he said. “And I consider rural North Carolina to be the legs and arms of our state.”

He also pointed out that more than 1,300 entities report to the Local Government Commission, and their staff is small.

It is labor intensive for the LGC to take over a town. According to LGC staff, it can take three staff members — two of those full-time —in the early months of intervention. If they can, LGC staff said they try to use the local government’s funds to hire “outside accounting help” so that LGC staff don’t get tied down.

The LGC intends to request funding for additional staff from the General Assembly this session.

Folwell said that it gives the LGC no pleasure to have to take over a local government’s finances.

“We are not in the position, nor do we desire to take over any of these entities,” he said, adding later: “That’s why we’re trying to work so hard to figure out what’s right, get it right, and keep it right.”