As policymakers push for higher third-grade reading proficiency and programs like Read to Achieve struggle to make a difference, colleges of education are finding ways to better prepare and support teachers, and teachers are finding ways to improve literacy instruction.

At the K-12 Literacy Summit, organized by the North Carolina New Teacher Support Program and East Carolina University’s College of Education, hundreds of district and school leaders and university faculty gathered in Greenville last week to share ideas and resources. Pat Conetta, the director of teacher instruction and development for the New Teacher Support Program, said the inaugural event had three main goals.

“We’re looking at pre-service preparation, induction support of beginning teachers, and community/university relationships,” Conetta said. He said more communication between universities and districts is needed to support teachers — especially those who just entered the classroom — improve instruction, and ultimately help students’ learning and outcomes.

Teaching literacy is complicated. Mastering the skill takes more than effective educator preparation, Conetta said. It’s a process throughout which teachers need support and new resources. A lot of the breakout sessions focused around what support, mainly coaching and professional development, is available.

“It spans this professional continuum from pre-service to hopefully it’s accomplished teaching practice,” he said. “And what preparation is needed, what supports, what ongoing supports? Just as we help readers develop, that’s a process… and the development of effective teachers or accomplished teachers is a process. And we have to acknowledge that.”

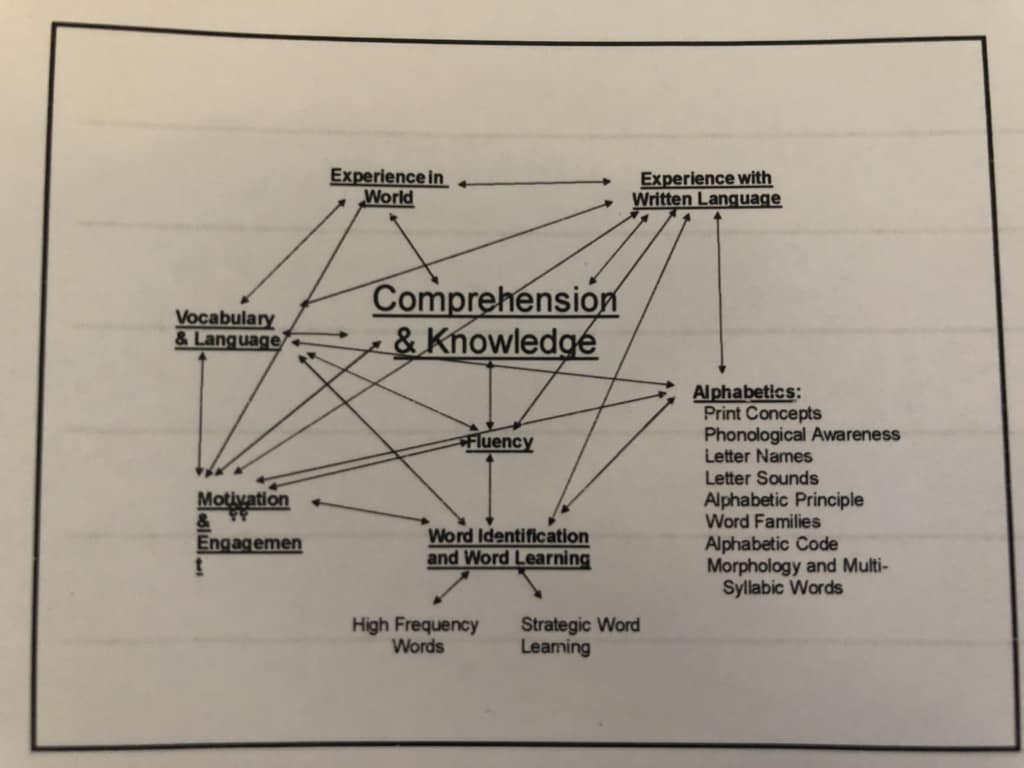

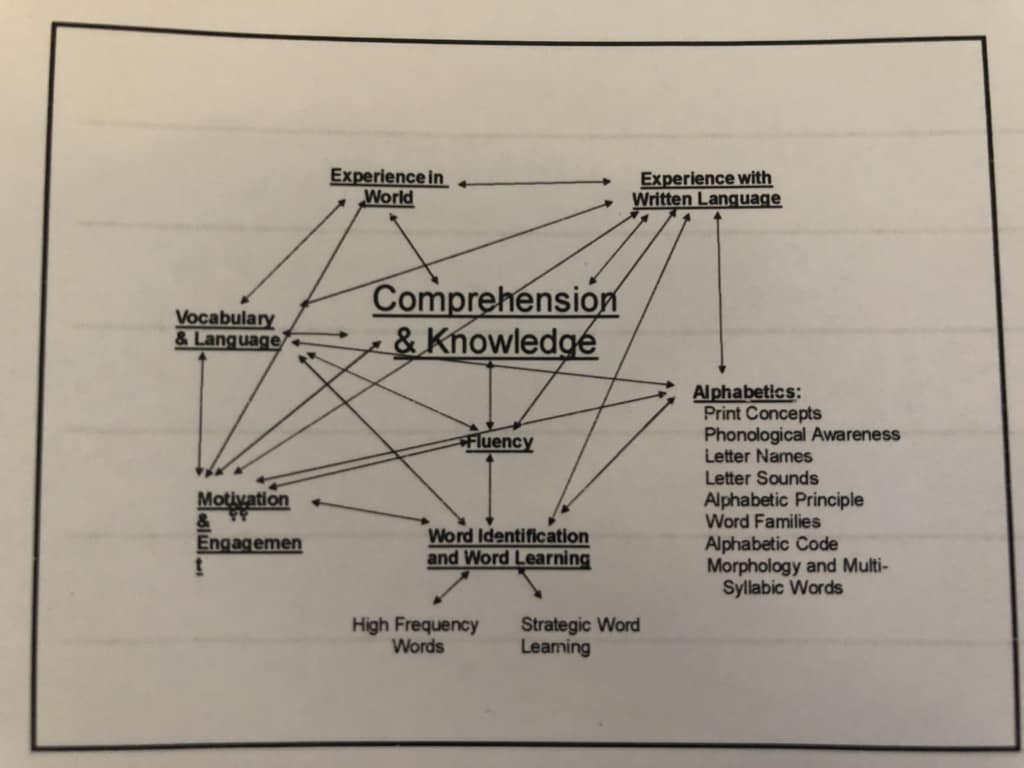

Donna Scanlon, a professor at University of Albany’s School of Education, has researched literacy and teaching literacy for decades. Scanlon broke down the complexities of how children learn to read in her keynote address and offered advice on where instruction strategies often fall short in teaching literacy. Take a look at this literacy model, which Scanlon presented at the summit, and try to imagine tackling literacy learning as a teacher.

Scanlon, who is also a licensed school psychologist, said she often found a need to work with teachers, instead of students or parents, in figuring out how to support kids who struggle to read.

“Kids who have difficulty getting going reading need teachers with expertise who can identify what the problem is and think about how to address it effectively for that child,” Scanlon said.

Let’s break down her presentation for a deeper look at the process of literacy. Scanlon’s first point? The foundational link between knowledge and comprehension. “The reason we read, the reason we teach kids to read, the reason we teach kids to write, is to develop knowledge and comprehension,” she said.

And those two factors, comprehension and knowledge, depend on each other. Scanlon said children from an agricultural background, for example, will more easily comprehend text about farming because they already have knowledge on the subject.

“We need to be thinking about the relationship between what an individual can comprehend and what they already know. So limitations in knowledge lead to limited comprehension. And knowledge develops through comprehension.”

Next is vocabulary and language. Scanlon explained that issues with reading are not visual but verbal.

“We now know that reading difficulties are due to verbal processing issues; they are not visual processing-related,” she said. “So if kids have limited oral language skills, they’ll have difficulty comprehending spoken and written language.”

Scanlon recalled that when she would observe classes of students who have limited language skills, she would often notice not much talking happened in the class. Other classrooms suffer from the same problem, she said. Students need more opportunities to talk and develop oral language skills.

“Kids need to use language to develop the language that will allow them to comprehend the texts that they’re ultimately asked to read.”

Vocabulary, she said, is directly linked to comprehension. Knowing more words in early grades, research has found, is a strong indicator of comprehension later on in an individual’s adolescent years.

“K-12 teachers need to be thinking across grade levels, ‘What are the kindergarten, first grade teachers doing that prepares the kids for what they’re going to be asked to do in 11th grade?’ We all have to work together is the message here.”

The third factor in understanding literacy is experience in the world. A student’s experiences impact her ability to comprehend, her vocabulary and language skills, and her written language skills. Scanlon gave this example:

“So if you’re going to take kids to an aquarium, and you read a book about penguins before they go, they’re going to take something different from that experience of going to an aquarium than they would if you hadn’t read a book,” she said. “Similarly, if you go to an aquarium first and then read a book about penguins, the kids are going to understand the book differently. So these are all mutually related, reciprocally related.”

Next is experience with written language. Scanlon said there is not enough writing happening in schools. Even before a child can write articulately, she said, it matters to develop the skill. The only way to get better at both reading and writing is to do more of it.

Alphabetic skills came next. When children first learn to read, they need to understand the idea that words are comprised of parts.

“So when we’re talking about little guys, 4-year-olds and 5-year-olds, their focus early on is becoming phonemically aware, which means that they need to understand that words are made up of smaller component sounds.”

Learning the names of letters, she said, often helps with the sounds of letters. Students start with learning the beginning letters and sounds, then the ending letters and sounds. They move on to digraphs and blends, vowels and vowel teams, and phonograms and word families. Throughout the development of this alphabetic code, “engagement in reading and writing helps to build knowledge about print and the alphabetic code,” Scanlon’s presentation reads.

Alphabetics do help when students are struggling to solve a word, but they do not have direct links to comprehension. That leads to the next component of literacy in Scanlon’s model, which is word identification and word learning.

“In order to read with comprehension, or to write with logic, kids need to be able to read most of the words with ease,” she said.

And if you do not know specific words, you will not be able to understand what is happening in the text. Alphabetic skills can help readers figure out unfamiliar words.

“If you’re having to figure out the words, you can’t be figuring out the message,” she said. “So kids who have well-developed alphabetic skills are able to puzzle through unfamiliar words and to derive at least an approximation of the pronunciation of the word.”

However, Scanlon said, “sounding out” a word is not always effective. Many English words are not decodable. Most students learn words from guided practice and the application of “word solving strategies,” which can not focus too much just on the alphabetic code or just on the context. Once a student solves a word multiple times, she will be able to identify the word, then eventually learn the word.

Scanlon said literacy programs that focus too much on phonics and alphabetics and not enough on comprehension miss the point and can make the learning process more difficult for students. Fluency, sometimes referred to as the speed and accuracy with which someone reads, is similarly emphasized too much, Scanlon said.

“Fluency is important only to the extent that that it enhances and reveals comprehension,” she said.

The last factor in literacy is motivation and engagement, which impacts every component of reading. Having teachers who sell reading as one of their favorite activities is crucial, she said. From years of work with intervention, Scanlon said there is no way to know how far a child can come who struggles to read.

“We need to make sure that teachers are relaying to kids that reading and writing are not work; they’re fun,” she said. “They’re interesting. They help us develop expertise about things we want to learn about. And you can do it, is the other part of the message.”

Mark A. L’Esperance, elementary and middle education department chair at East Carolina University and lead administrator with the New Teachers Support Program, said this summit is hopefully the start of more understanding around different approaches to literacy and more harmony between different ends of the education system.

“Education’s a puzzle, right,” L’Esperance said. “A 500-piece puzzle or 1,000-piece puzzle. Everyone knows their piece, but how do we connect the pieces? I think that’s probably the bigger thing that we’re trying to do.”

Conetta said he hopes to host a similar event in the western part of the state next.