“You don’t know how to read the music?” I asked, completely surprised.

“No, God, no! I don’t want to know it!” Joe Thrift said. “I play by ear.”

I had just watched Thrift playing the fiddle along with his students in a break-out jam session in the middle of his class. He’s not a music instructor, however. He actually teaches students how to make violins.

Can’t make violins without playing em @surrycc. I may need to come back to take this class. @EducationNC @Awake58NC @NCCommColleges #Awake58 pic.twitter.com/MlkKrOM9hK

— Yasmin Bendaas (@yasminbendaas) August 29, 2018

Thrift taught himself to play the violin in his mid-20s and traveled across North Carolina and Virginia searching for apprentice work in making the instruments — with no luck. After being shown an ad in The Strad magazine, he applied and was accepted to violin making school in England in the 1970s.

“I was there three years for school, and then I came home and started a shop and hated running a shop,” Thrift said. “I wanted to be a maker, not a repairman.”

Now in his sixth year teaching violin making at Surry Community College, Thrift’s class has grown from one class with 12 students to five six-hour classes per week.

Student Eliot Smith attends all five classes and has been taking violin making at Surry for the past five years, beginning in his sophomore year of high school.

“I just really enjoy the instrument building. I’ve played music since I was 2, and I’m actually currently touring full time with a band,” Smith said. The band he plays in, Cane Mill Road, peaked at number 10 on the Billboard Bluegrass charts in August for their most recent album, Gap to Gap.

Smith’s music career is taking off alongside his violin building — he recently was accepted into a full-time violin making program in Boston and wants to make violins professionally. Over the past five years in Thrift’s class, Smith has already completed five violins by hand.

“There’s definitely something really satisfying about using the hand tools,” Smith said. “There’s also a demand with instruments, getting an instrument that was made with hand tools. People would rather have one that someone used their hands on and really worked on in that way.”

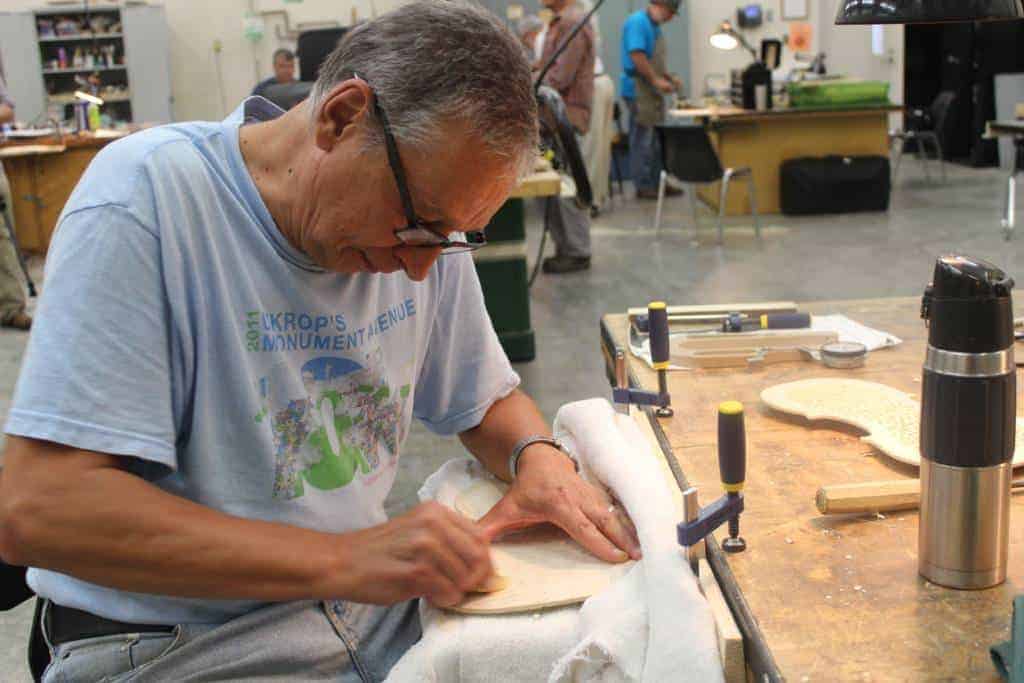

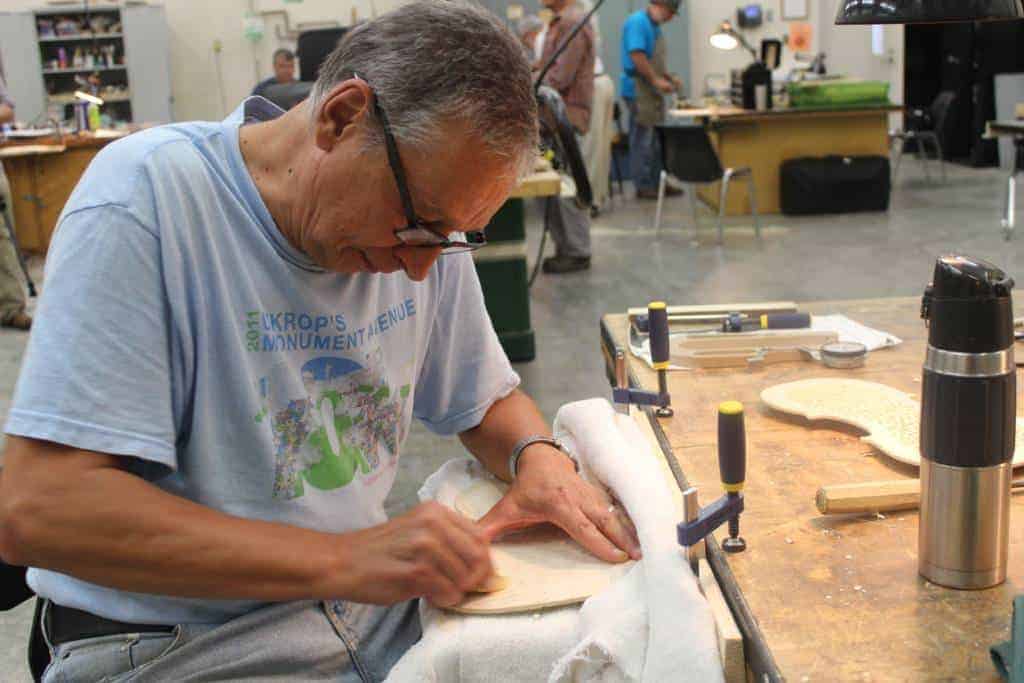

Because of the use of hand tools instead of power tools, Thrift says the craft is “a different world altogether” when it comes to woodworking. Even for a pro like Thrift, making one violin takes about 200 hours.

“What goes into it? A lot of patience and hard work,” Thrift said. “It’s a huge process.”

Still, violin making is more than crafting the physical shape of the instrument. There’s a science to making the sound, and it starts with the raw materials — the wood.

“We’re using European woods. The backsides and the neck are curly maple and the top is spruce,” Thrift said. “Pianos, guitars, mandolins, all of them have the spruce top. Spruce is the soundboard of all that kind of stuff. It’s lightweight and resonant and strong.”

Then there’s mastering the different levels of thickness required of the wood. At one of the worktables, a student sat over a growing pile of wood shavings on the floor.

“This is the back, and I’m scraping the inside in order to graduate the thickness,” he explained.

The templates that students use are copies of some of the best violins ever made.

“I make copies of Guarneri ‘del Gesù,’ who was a contemporary of Strad,” Thrift said. “My best friend is this guy, Roger Hargrave, who’s a maker who lives in Germany but he’s English, and he’s like the most famous violin maker in the world.”

“He came here last year and gave a talk to the class,” Thrift said. “I’ve gotten all my information about ‘del Gesù’ through him because he’s like the Mac Daddy of Cremonese violins. You know Strad, Guarneri, Amati, all those guys were from Cremona, Italy. He’s like the foremost expert on those instruments.”

But how can you tell a really good violin? According to Thrift, it’s all in the varnish.

“The varnish is what makes or breaks violins,” Thrift said. “There’s nothing I could tell anybody that they could go out and recognize a great violin. It’s just from looking at instruments and making instruments and looking at the quality of the work, and mainly the varnish.”

Thrift’s expertise means he not only teaches at Surry, but also makes and sells his own violins. The main shop he sells in is in New York on Broadway; many of his buyers are Juilliard students.

“So I sell in the classical world although I play old-time fiddle,” Thrift explained.

Teaching, however, has become a love for the instructor.

“I love it. Or I wouldn’t be doing it,” Thrift said. “I would be long gone if I didn’t love doing it.”

His passion and skills have drawn students to Mount Airy from as far away as Utah and Portland. In comparison to most violin making schools, which — according to Thrift — are at least $17,000 a year, students find a great value at Surry Community College.

“The way I set the course up, I wanted it to be so that if a musician wanted to come in here and make a violin, they could come in and all they had to do was buy their wood,” Thrift said. “We’ve got tools. We’ve got all the equipment and everything that anybody would need.”

Though it takes most new students a couple years to make their first violin due to a process that Thrift calls “about as tedious as it gets,” his classes have continued to grow because “none of them were quitting.” Despite the time and effort, he doesn’t discourage anyone from violin making.

“I think anyone can build one,” Thrift said.