Claudia Walker taught at Murphey Traditional Academy — a public, magnet, Title I school in Guilford County for 14 years. From 2010-2015, she was an awardee of Burroughs Wellcome Fund’s Career Awards for Science and Mathematics Teachers (CASMT). The grant offers math and science teachers $175,000 over five years for professional development, extra salary support, and equipment. Below is an interview with Walker, edited for clarity, regarding the CASMT grant and how it impacted her teaching and her school.

Bendaas: How did you originally hear about the CASMT grant?

Walker: I believe it was [in] one of those informational e-mails that was sent out to all principals, and then my principal handed it to me and said, “I think you should really apply for this award.”

Bendaas: Can you tell me about your background in getting into math and science education?

Walker: I’ve been teaching since 1992, and I’d originally been hired as a math teacher. Then I was basically a classroom teacher — I taught all the subjects. And then Guilford County had a “math initiative” … where they were trying to promote more focused math instruction across the county. I attended several of these sessions, and then after that I departmentalized and just became a math teacher.

Bendaas: Since you have been teaching for so long, what were some of the challenges that you were seeing before the grant, and how did the grant help you address them?

Walker: The biggest challenge we had at Murphey was that we were a magnet, we were Title I, but we didn’t have much technology in the classroom. A lot of new schools were being built across Guilford County, and when I visited these schools, they had projectors and … some classrooms had computers or 1:1s for upper grades. I noticed we didn’t have any of that.

In talking to my principal, I knew that we needed to address math at Murphey because our math scores were low. Our reading scores were really high. I wanted to tackle the whole, “Let’s approach math differently.” So when I originally applied for the CASMT, my goal was to be trained as a math coach and then to bring technology to Murphey, and that’s what I was able to do.

Bendaas: Can you tell me a little bit more about your training as a math coach?

Walker: When I originally wrote the CASMT, I had not heard of Singapore Math. But in writing the CASMT award, saying I wanted to be trained as a math coach, I was going to attend the National Council of Teachers in Mathematics conferences and basically get to know more about math and how to approach it differently. But within that year — so 2010 was when I got the CASMT — I heard about Singapore Math, and then in 2011 I applied with the Singapore Math pilot that was also being sponsored by Burroughs Wellcome. That took me, along with my original plan to be a math coach, in that direction to really learn about Singapore Math.

I went to conferences, independent [professional development] sessions, and really tried to get my hands on as much information and training that I possibly could for Singapore Math. Since we had the pilot backing us up as far as materials and professional development for the teachers, we were able to really get into Singapore Math and become a Singapore Math pilot school.

Bendaas: This funding is a really large grant over five years. It’s a $175,000 grant. I’m assuming this impacted not only you and the skills that you were able to learn, but your school much more broadly. Can you tell me about that aspect?

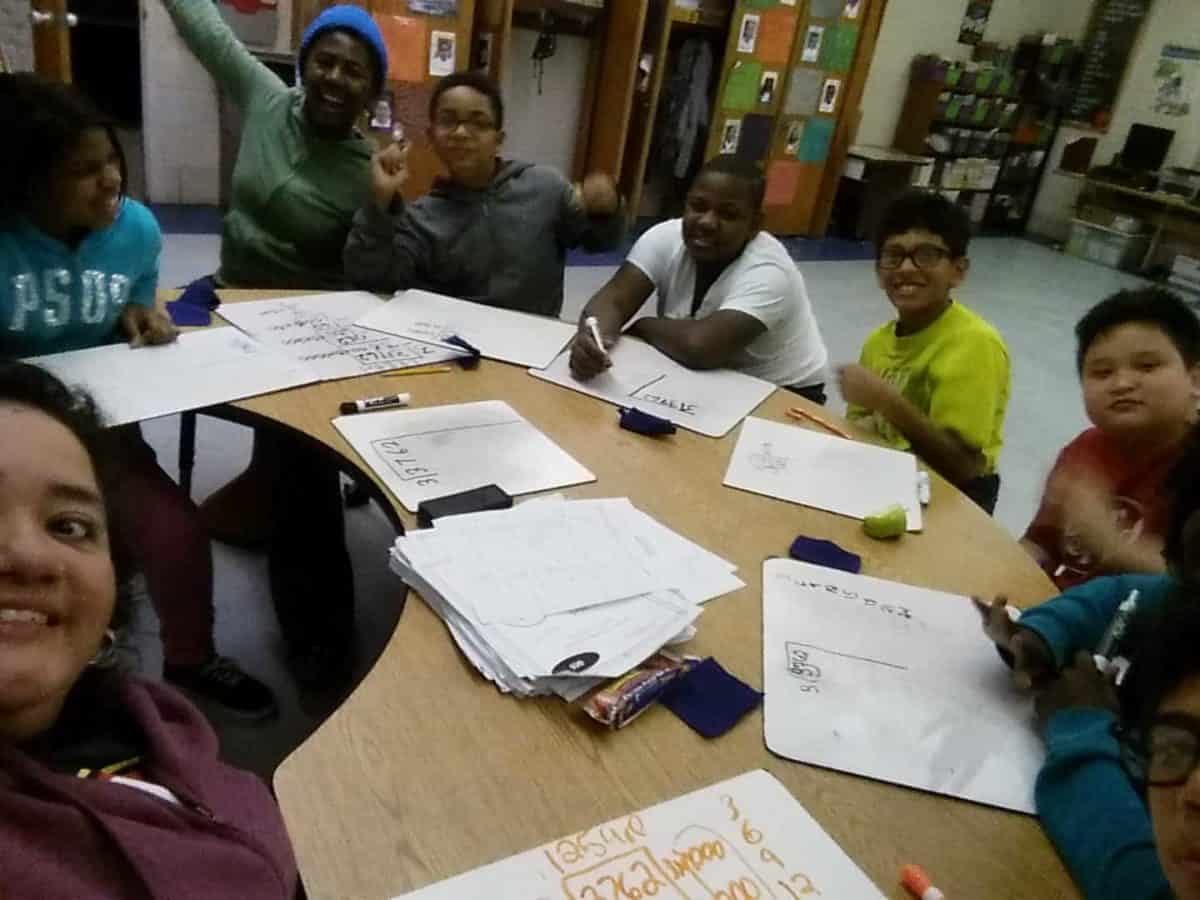

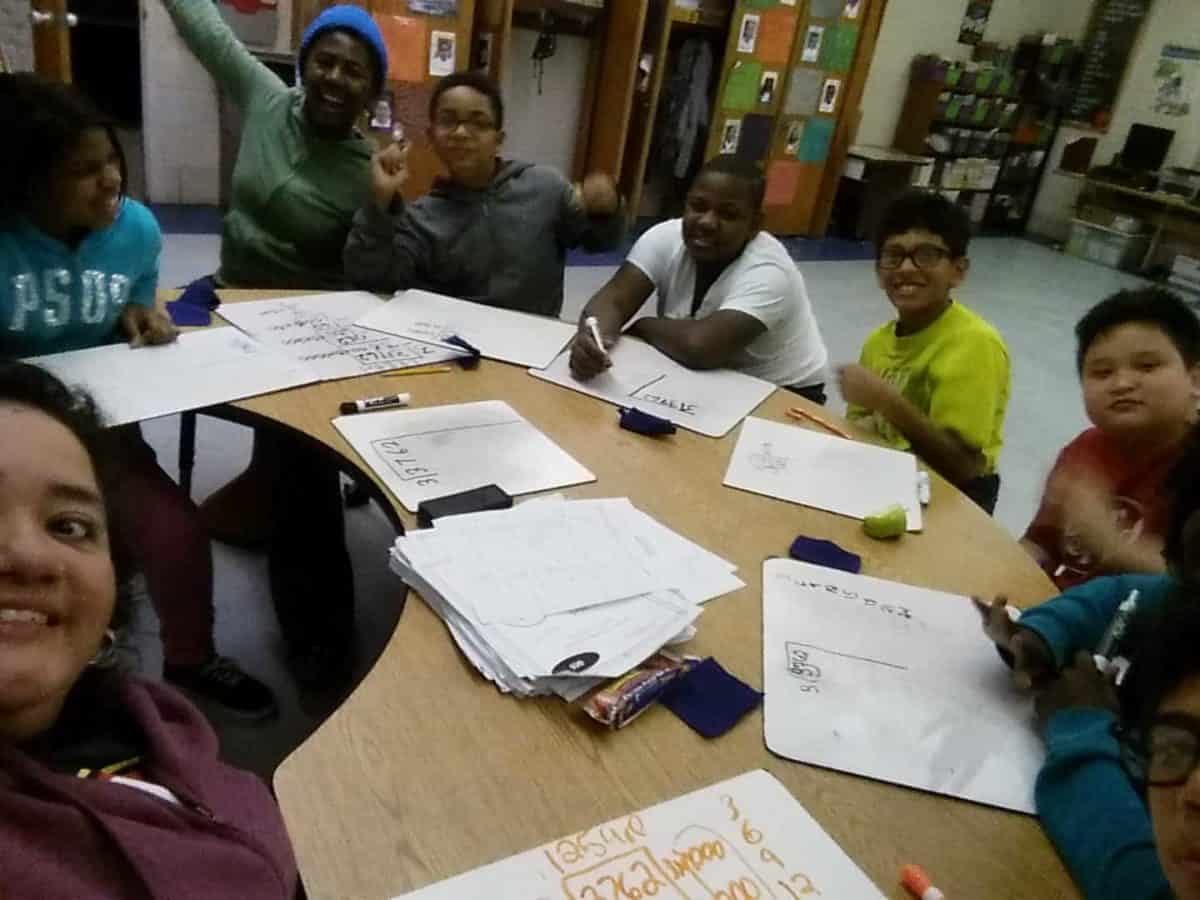

Walker: I handpicked a couple of my colleagues. I took them to different trainings. We went to math conferences, science conferences, technology conferences — all of these different professional development opportunities. I had that team of teachers that [was] really into it. They would then turn around and present it to their grade level teammates, because they were from different grade levels. Then I was able to get projectors and document cameras into the classrooms so that the teachers could really use these to enhance their teaching. The teachers who I had on my team came back and then they modeled lessons for the other teachers … We were able to really get the other teachers to buy into the idea of not only teaching math differently, but teaching math differently using technology tools, more hands-on.

It made a difference because our school now, our math scores are pretty much — they’ve gone up. We’ve closed the gap between reading and math without bringing reading down. We wanted to make sure that our kids “spoke more math” if that makes sense. We wanted them to be more math oriented, so we developed trainings around “math talks” where there would be more conversation [and] less [of] teachers talking and more [of] kids doing. [It] was a big turn around for our school because most of our teachers have taught math the way they’ve been taught, which is [a] “teach, teach, teach, do the problems” kind of thing. We turned it around to the point where teachers are now knowing how to question the students, how to get the students more engaged in talking.

We did a survey with the kids last year or two years ago with a group that Burroughs Wellcome had hired to do an analysis of how the school had changed. The students showed more interest in math. They said math was fun. The teachers felt that there had been a big change at school, that they felt more confident teaching math.

Bendaas: The CASMT grant is open to both primary and secondary schools. But especially in K-5, why are science and math so important?

Walker: When you’re a young child and you’re taught math and science in isolation, in a silo so to speak, they don’t see the big picture. They don’t see the “What can I do with this? Why am I learning this?” which is a very typical question kids ask across the board.

We’ve brought in STEM at Murphey … so kids can now see that science and math are relative to the real world. They can then start looking at — not so much at the careers they’re going to do, because no child picks their career at fourth grade and is successful with that — but their path has been widened as opposed to just being “I can’t do math, so therefore all of these careers are out the window” or “I don’t understand science” or “I hate science,” so another branch of careers are gone out.

[Through] teaching them that math and science are not only necessary everyday, but that everything they do has been influenced by mathematicians and scientists, then they can actually see “there are so many things that I can do.”Bendaas: Why do you think that an award like CASMT is so beneficial to North Carolina teachers in science and math?

Walker: I had taught for about 15 years prior to the award. I had been teaching for awhile. Being in the first cohort, I didn’t know what to do … I was allowed to leave my little corner of the world, my classroom, and go and explore what was out there because I had the funding for it. I was able to go to Indianapolis to a math conference. I was able to go to Houston to learn about science. I was able to really network with teachers [and] colleagues that were like-minded and able to see what was out there and bring that back to Murphey.

When I first started the award, I had no idea what STEM was. Maybe I had heard about it here and there, but I never really knew what it was, and now I’m looking at possibly getting a doctorate in STEM education. I’ve run the gamut of didn’t know anything about it to “Oh my gosh, we’ve got to promote this. We’ve got to make sure our kids have the exposure to STEM and really know what it’s about.”

Bendaas: Is there anything else you would like to add about the award?

Walker: One thing that I always admired about Burroughs is that they’re so responsive to a teacher and a teacher’s needs. They know what we need. They know what we’re looking for. The group of teachers that were first selected was an opportunity for me to see what was going on across North Carolina.

The networking, the being able to really get out there, the building the teacher’s confidence … You feel pretty confident about what you’re doing in your own classroom, but being able to become a leader in this field, being able to really take what I know and bring it to other people has been life-changing for me.

I’ve never considered myself a teacher-leader, and now I think I am. I can see opportunities. I can see colleagues. I can put a hand out to other teachers who say, “Oh, I don’t know” or “What difference can I make?” or “I’m only a classroom teacher,” which I hear a lot. [I can actually empower] them and make them realize that there are things out there that we can do and make a difference in our students’ lives.

Want to talk to more CASMT awardees to learn more? Join us this Thursday, August 2nd at 7PM for a live Twitter chat where you can ask your questions. More info below.