At the request of the legislature, a study is underway on whether larger local school districts across the state should be divided into multiple districts.

“There are debates in several counties on whether the school systems are too large and whether or not they should be broken up,” said Rep. Bill Brawley, R-Mecklenburg, the House chair of the Joint Legislative Study Committee on the Division of Local School Administrative Units in its first meeting Wednesday.

“Those debates tend to go primarily on the basis of opinion, not fact. The purpose of this committee is to study that issue and generate some facts to inform the debate.”

Brawley said the committee’s goal is not to create legislation to divide districts but to produce a report with information on the effects of district size and divisions. There have been conversations around the issue in larger districts like Charlotte-Mecklenburg and Wake County.

“I doubt if we will have enough data at the end of this short process to even generate a procedure, but we do intend to inform the debate, clarify the issues that need to be addressed because I do not see this debate going away,” he said. The audience outnumbered legislators, and Brawley noted, “We’ve got more staff here than anybody else.”

The few legislators present heard presentations from fiscal staff on the legislative history of school districts, the structures that fund those districts, and how students perform academically in varying sizes of districts.

Kara McCraw, a staff attorney and legislative analyst for the General Assembly, said there is no state statute around the division of school districts.

The closest example to a school district division, McCraw said, was in 2016 when legislation changed funding sources for students within the district lines of Nash-Rocky Mount Schools who live in Edgecombe County’s geographic lines. If the funding was not provided as deemed necessary by the local government, the legislation ordered the part of the Nash-Rocky Mount district inside Edgecombe County to return to Edgecombe County Schools.

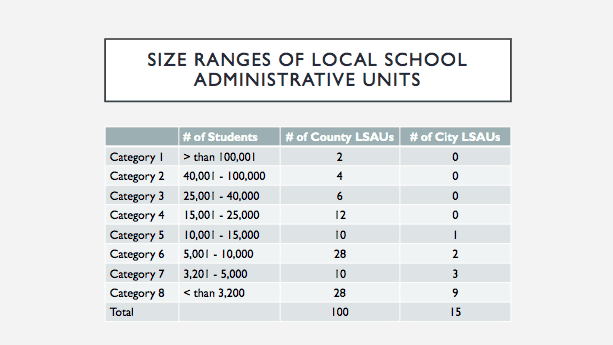

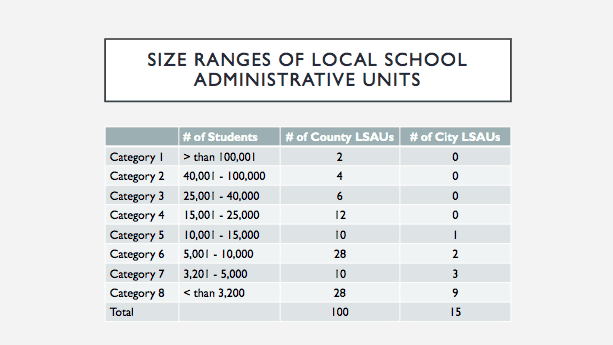

From 1870 to 1957, she said more than 70 city districts were created, but many have since merged back into the county system — Charlotte-Mecklenburg is the result of one of those mergers. No new local districts have been created since, but more mergers have occurred, both within and outside county lines. There have been 115 local districts since 2004 — 100 county districts and 15 city districts.

Sizes vary widely over those districts. Roughly a third of the state’s students attend one of the five largest districts. However, more than half of districts have less than 10,000 students. Thirty-seven districts have less than 3,200 students, as seen in the table below (full presentation here).

The merging process can happen through a combination of decisions by county commissioners, local school boards, the State Board of Education, and the state legislature. If a district elects to dissolve, it is the state board’s responsibility to integrate those students back into the appropriate district.

Sen. Joyce Waddell, D-Mecklenburg, said she wanted to stick to the purely informative mission of the committee. She said she is concerned about the possibility of district division as it relates to equity.

“The point is to make sure that as we remain strong as a system that all of our students get a great education and that it mirrors what they will see in the world of work when they leave the school system,” Waddell said. “I don’t want to see us break up and have a school system with the haves and have-nots.”

Legislative analyst Brian Gwyn shared academic performance of students in districts of different sizes. He said there are several reasons besides size that cause certain district populations to outperform others. Resources like local funding for capital expenses and teacher compensation are often more abundant in the state’s larger and wealthier districts.

“A more detailed study would likely be better to actually … in a more scientific way, determine the influence of school district size on academic outcomes,” Gwyn said.

According to 2016-17 academic data, in the two largest school districts, with more than 100,000 students each, students had higher proficiency and career and college readiness according to median and weighted average district composites of test scores (end-of-grade tests in third to eighth grades and end-of-course exams in certain high school courses). The weighted average reflects differences in enrollment across districts.

The 12 districts with between 15,000 and 25,000 students had the lowest median performance. The state’s smallest districts, with less than 3,200 students, had the lowest career and college readiness composite score under the weighted average.

The same trend exists for third grade reading test scores — the highest composite scores (when considering both the median and the weighted average) came from the two largest districts, and the lowest scores came from the 12 districts with 15,000 to 25,000 students.

Schools with 10,000 to 15,000 students had the highest median four-year cohort graduation rate. The highest median five-year cohort graduation rate was in schools with between 25,000 and 40,000. The lowest median four and five year cohort graduation rates were in schools with between 5,000 and 10,000 students. When looking at the weighted average, the highest four and five year cohort graduation rates came from the two largest districts, while the lowest came from the state’s 37 smallest schools.

According to EVAAS data, which measures student growth based on past performance, the highest median percentage of schools that either met or exceeded that standard was in schools with between 40,000 and 100,000 students, which are still four relatively large districts. However, the lowest median percentage of schools that met or exceeded growth was in the two largest school districts.

None of the districts with more than 25,000 students were considered low-performing. Neither were any districts with between 10,000 and 15,000 students. A district is deemed low-performing if the majority of schools in the district received Ds or Fs in performance grades based 80 percent on test scores and 20 percent on EVAAS growth and did not exceed EVAAS growth.

Seventeen percent of the districts with 15,000 to 25,000 students were deemed low-performing, and about 14 percent of the state’s smallest schools (with less than 3,200 students) were considered low-performing.

Eric Moore, another fiscal research division staff member, presented on the funding structures for both county and city districts. He explained that city and county districts are treated mostly the same when it comes to funding. There are certain supplemental funds that only county districts receive based on characteristics of income, size, and special needs of its student population. He said providing certain base funding all districts receive regardless of size would create a cost to the state.

“Taking the same number of students and dividing them across more school districts will increase the cost to the state in these areas if these formulas remain in tact,” Moore said.

The committee will next meet on March 14 to discuss issues district divisions could create. The group will meet two more times after that date, Brawley said, to consider nationwide trends of student achievement based on district size and methods large school systems across the country are using to meet the needs of their populations.