The Joint Task Force on Education Finance Reform kicked off yesterday, but co-chair Rep. Craig Horn, R-Union, said its agenda is not going to be simple.

“This is going to be a heavy lift for everyone in this committee and frankly for all of us in the state,” he said. “When I say heavy lift, I mean really heavy lift. There’s going to be a lot of homework, a lot of reading, and a lot of contemplation.”

The issues tackled by the task force date back to committee meetings last year that explored the problems with the current allotment system of funding distribution and suggested a new funding system was possibly needed. The challenges were the focus of a study by the General Assembly’s Program Evaluation Division (PED).

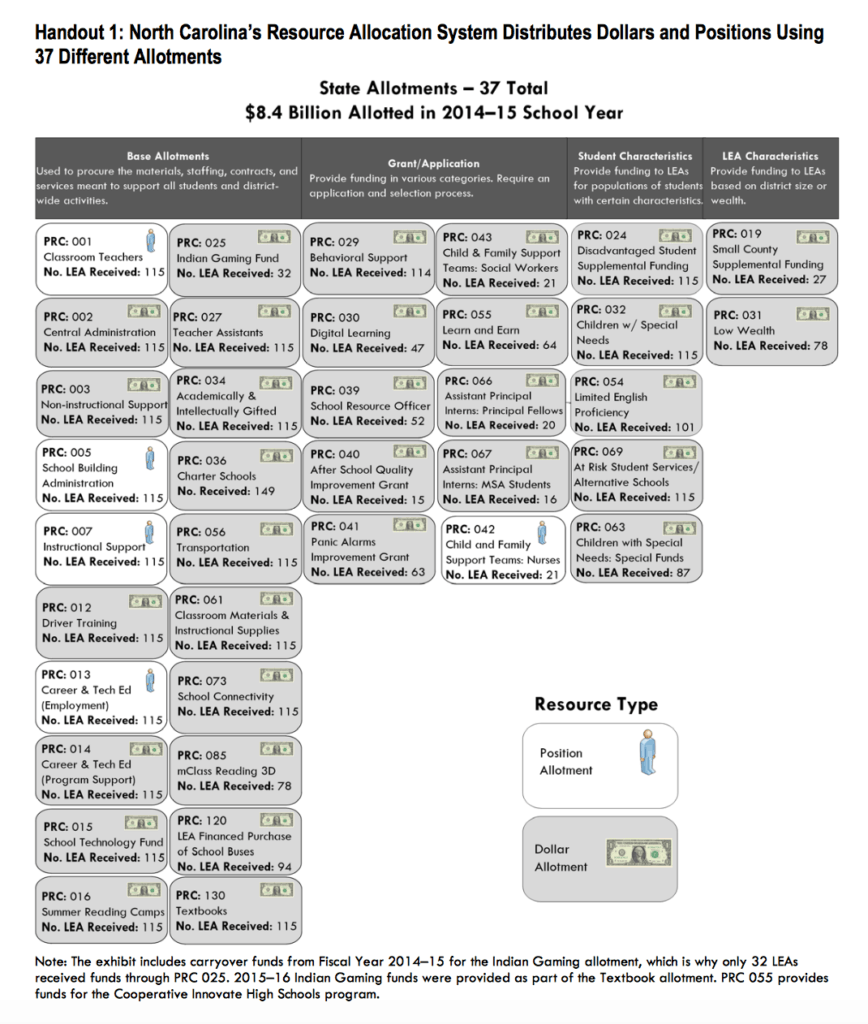

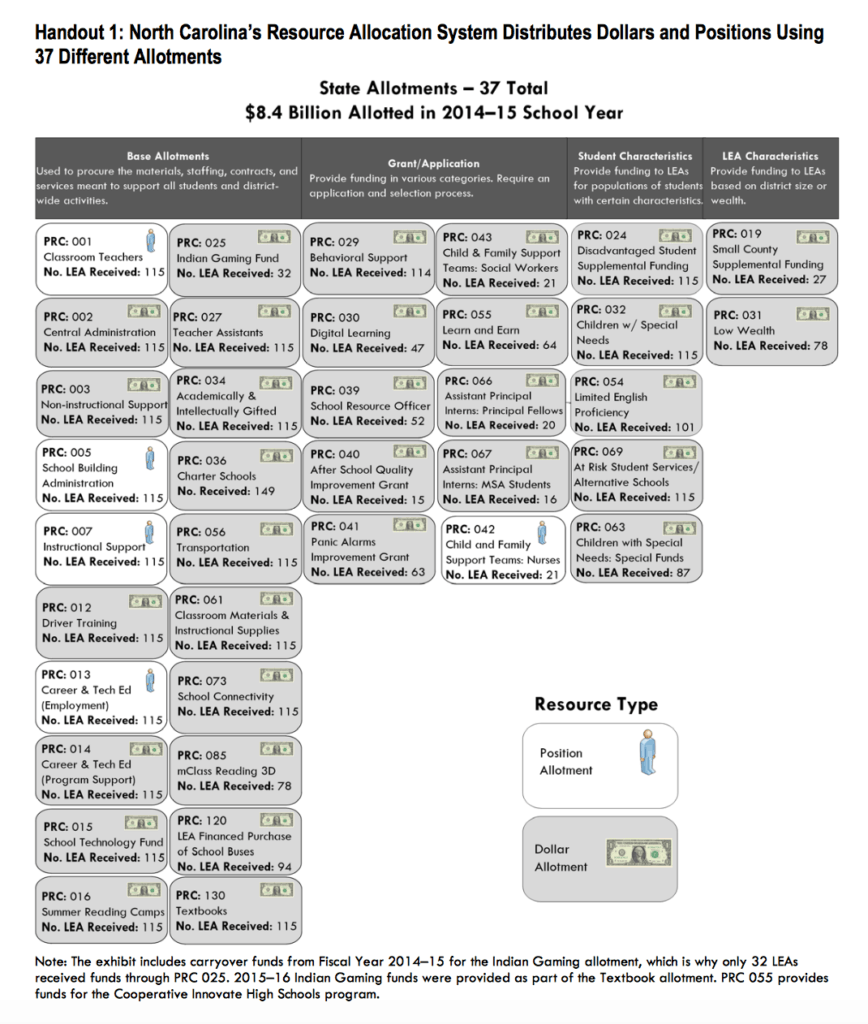

Presently, the state doles out funds using a series of allotments — 37 in total. The allotments are essentially line items designating a specific amount for classroom teachers, an amount for school building administration, etc. This is called the Resource Allocation Model.

According to the presentation on PED’s study, there are serious issues with the system.

For instance, one of the findings of the study is that the classroom teacher allotment structure favors wealthy counties. Another finding says that the allotment for disadvantaged students gives disproportionate funding across school districts.

There were seven findings related to allotments in whole.

1: The structure of the Classroom Teacher allotment results in a distribution of resources across LEAs that favors wealthy counties.

2: The Children with Disabilities allotment fails to differentiate based on the instructional arrangements or setting required and contains a funding cap that results in disproportionately fewer resources going to LEAs with the most students to serve.

3: The allotment for Limited English Proficiency (LEP) students contradicts the principles of economies of scale and contains a minimum funding threshold that results in some LEAs serving LEP students without funding.

4: The allotment for small counties is duplicative and is not tied to evidence regarding costs of operating small districts.

5: The Low Wealth allotment formula does not rely on the most precise means of calculating an LEA’s ability to generate local funding.

6: The allotment for disadvantaged students provides disproportionate funding across LEAs.

7: Funding for central office administration has been decoupled from changes in student membership, creating an imbalance in the distribution of funds.

During the presentation, legislators also heard about findings related to system-level — high-level — issues with the allotment system the state used. There were five:

1: North Carolina’s allotment system is opaque, overly complex, and difficult to comprehend, resulting in limited transparency.

2: Problems with complexity and transparency are exacerbated by a patchwork of laws and documented policies and procedures that seek to explain the system.

3: Allotment transfers — a system feature intended to promote LEA flexibility — hinder accountability for resources targeted at disadvantaged, at-risk, and limited English proficiency students.

4: Translating the allotment system for funding LEAs into a method for providing per-pupil funding to charter schools creates several challenges

5: Using a weighted student formula is feasible and offers some advantages over the present allotment system, but implementation would require time and careful deliberation

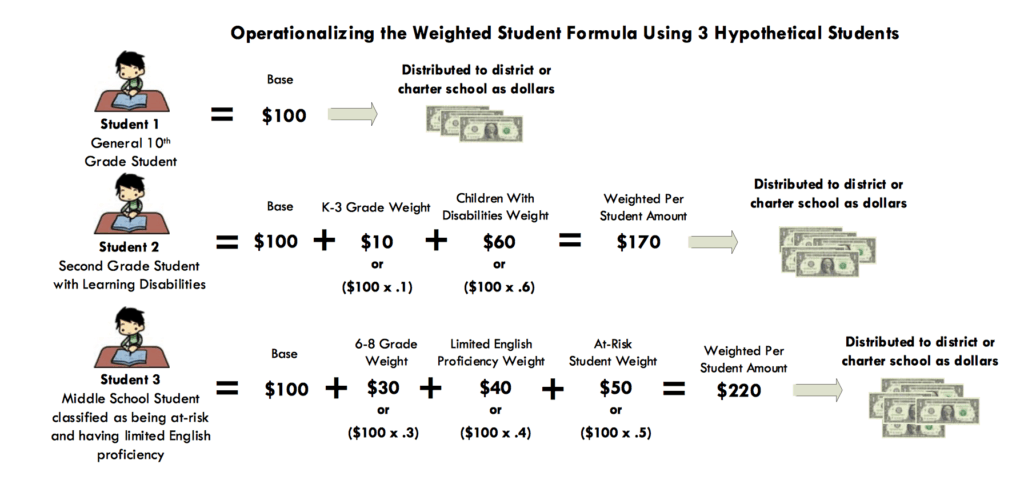

That last finding — the feasibility of using a weighted student formula — was the focus of the rest of the presentation.

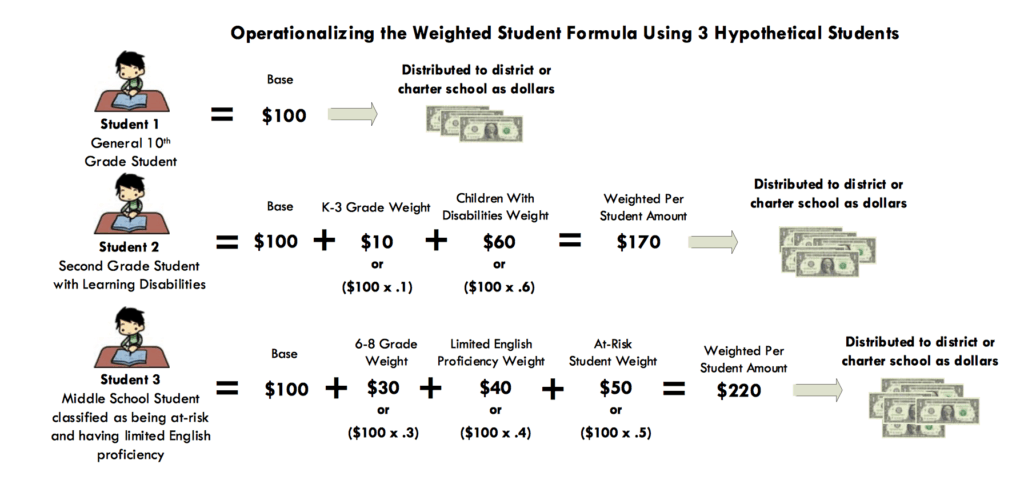

In this formula, rather than using a series of allotments, the money given to schools would be based on the student. The state would allocate a base amount of money for each student in the state. The arbitrary example given at the meeting was $100 (note: that is not the funding number being proposed, simply a number picked to use in an example for simplification purposes).

The distribution of funds changes depending on the type of student. A typical student with no special needs affords the school $100. But a student who is in 2nd grade may get an extra 10 percent of that $100, or $10 because the student is in the K-3 category. If the student has a disability, the school receives an extra 60 percent of that $100 base, or an additional $60 dollars. When all the numbers are added up on that student, the school gets a total of $170 for that one student.

Schools are funded based on the number of students. Typical students receive the base $100, and extra money is allotted depending on any extra needs or situations students might have.

During the presentation, legislators learned that only seven states still use the kind of funding formula North Carolina uses. The committee is supposed to explore different types of weighted student formulas and come up with a new funding model for North Carolina public schools. There is no one model that could be adopted from another state, according to Sean Hamel, principal program evaluator of the Program Evaluation Division of the General Assembly, who presented before the committee.

The legislation establishing the committee charged the committee with eight tasks.

1: Review the State’s current public school allotment system and undertake an in-depth study of various types of weighted student formula funding models. In its study, the Task Force is encouraged to consider models used by other states.

2: Determine the base amount of funds that must be distributed on a per student basis to cover the cost of educating a student in the State.

3: Identify the student characteristics eligible for weighted funding and the associated weights for each of these characteristics.

4: Resolve the extent to which the base amount of funds to be distributed would be adjusted based on the characteristics of each local school administrative unit.

5: Decide which funding elements, if any, would remain outside the base of funds to be distributed under a weighted student formula.

6: Study other funding models for elementary and secondary public schools, including public charter schools, in addition to the weighted student funding formula.

7: Study funding models to provide children with disabilities with a free appropriate public education. This shall include a consideration of economies of scale, the advisability and practicality of capping additional funding for children with disabilities, and additional costs associated with services required for particular disabilities.

8: Study any other issue the Task Force considers relevant.

Horn addressed the fact that this study committee will not actually discuss whether the amount of funding for K-12 education is appropriate.

“Some people have taken us to task for not dealing with that,” he said. “But adequacy is a different issue.”

He also warned that possibly changing the funding system could provoke a lot of criticism.

“They’re going to be people who are going to be very protective of the current system, because it benefits them, or at least they think it benefits them,” he said.

But he emphasized the need to conduct this study regardless.

“Any system of fund distribution…that is more than 20 years in existence, deserves and needs significant change because this state has changed significantly in the last 20 years,” he said.

Sen. Jerry Tillman, R-Randolph, chimed in at the beginning of the meeting, saying he hoped the difference in funding between traditional public schools and charter schools would be addressed over the course of the study committee’s life.

“We want to make sure we give that thorough coverage,” he said.

Tillman also criticized the current funding model, saying that through it, the state is dictating to local school districts how they should spend the money.

“Why in the world do we want to do that?” he asked. “Give them the amount of money and say, ‘Here go at it.’”

He said he was in favor of finding a way to give local districts more flexibility on how they spend their money and suggested giving districts block grants — money to use as they see fit — would be a good idea.

Rep. Hugh Blackwell, R-Burke, said he agrees that a new funding system should allow local districts more flexibility in how they spend money. But he had a caveat.

“At the same time, I think this committee needs to give some thought as we might move in that direction…to how we set standards so that flexibility doesn’t become simply an opportunity for LEAs to fail to meet the needs of students,” he said.

The committee also heard from Adam Levinson, chief financial officer of the state Department of Public Instruction.

Levinson started with a presentation examining the best way to look at finance funding reform but was cut off by co-chair Sen. Michael Lee, R-New Hanover, who said that Levinson was brought in to respond mostly to the PED report. Levinson apologized for misunderstanding why he was there and made some brief comments.

“We acknowledge that that system (the current funding system) is ready for a deep review and that there are opportunities to improve it, and we intend to be your partners,” he said.

Levinson also said there were some parts of the study he and his team dispute, though he did not go into specifics during the meeting. A letter from former DPI Chief Financial Officer Philip Price laid out some of the points of disagreement. The letter is in the report and can be found starting on page 69.

In the letter, Price went through each of the findings and identified the points of agreement and contention. For instance, in the letter Price disagrees with finding one, saying that the structure of the classroom teacher allotment does not disproportionately favor wealthy counties, as the finding states. The letter also disagrees, in part, with the notion that the allotment funding system is overly complex and difficult to comprehend.

In the closing comments, the letter goes on to say that to accomplish the objectives of fairly distributing $9 billion to serve North Carolina’s 1.6 million students equitably, and in such a way that the money is used correctly, the process can become complicated.

“The report effectively defines the challenges and possible issues with current funding formulas; but, the report does not outline how its revised formula options will address those challenges without ignoring or exacerbating other shortcomings. It is important to clearly identify the objectives of the funding model and assuring that the State meets those objectives during implementation. As referenced in the report, changing funding formulas must be carefully considered and systematically implemented,” the letter stated.

The next meeting of the committee will be November 15. The committee is expected to make recommendations to the full General Assembly in late 2018, but Horn said the committee may need more time.

Correction: In the original version of this article, the percentages in the weighted student formula calculations were incorrect. They have been corrected.