As Edgecombe County’s school system faces another hurricane season, its leaders are looking for ways to better understand the students and families they serve.

Anxieties were beginning to lessen Friday as projections for Hurricane Irma headed west — away from the community still recovering from last year’s Hurricane Matthew devastation.

Edgecombe County Public Schools (ECPS) spokeswoman Susan Hoke said the district is prepared for potential damage. County officials picked two locations — a private school in Tarboro and a Baptist church in Pinetops — to open as shelters for displaced residents if necessary.

“It doesn’t look like it’s going to be nearly as bad as we thought,” Hoke said. “Of course, we didn’t think that with Matthew either.”

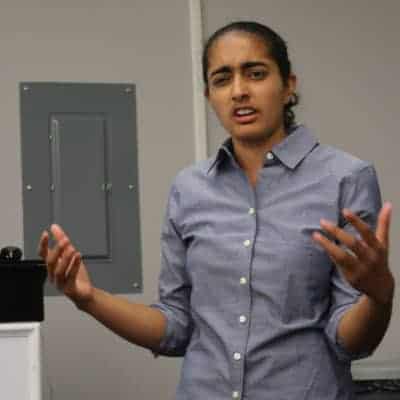

But on Thursday, when Irma’s path was less clear, school system leaders met to address greater issues embedded in the community. Former teachers in eastern North Carolina, Seth Saeugling and Vichi Jagannathan have researched the effects of trauma on families for months, focusing on east Tarboro. Their research is funded by an anonymous private donor and is housed within the Public School Forum of North Carolina. They presented their insights from interviews and meetings to representatives from several sectors: health, law enforcement, church, social services, and education.

“I believe it’s possible to break the cycle of trauma,” Saeugling said. “And that belief isn’t like pie in the sky. That’s rooted in science. That’s rooted in belief in people and community.”

Adverse childhood experiences, commonly referred to as ACEs, often show up in the form of abuse, neglect, or household dysfunction. Saeugling and Jagannathan emphasized the importance of the first three years of humans’ brain development. Eighty percent of the neural connections a brain makes in a lifetime, according to their presentation, occur in those three years. Traumatic events force young people deal with toxic stress, which is intense, prolonged, and prevents healthy brain development.

These traumas have been compounded by devastating natural disasters; both Hurricane Floyd in 1999 Hurricane Matthew in 2016 displaced hundreds and forced the historic town of Princeville to consider permanent buy-outs of their homes and leaving behind an entire town. Saeugling said the stress both children and adults are under, however, can feel like constant danger is imminent.

“Hurricane Matthew came last fall, and the hurricane is super real, and its impacts are super real,” Saeugling said. “But our kids get hit with a hurricane every day, and the hurricane is ACEs and trauma. And that reality is tough to grapple with.”

An individual who experiences trauma creates coping behaviors that often further harm themselves, like self-harm, aggression, or abuse, Jagannathan and Saeugling explained. Parents commonly lack the ability to understand where those behaviors stem from and may themselves be unable to respond positively due to their own trauma-caused mechanisms.

“When a parent is in trauma, their own survival mode makes it impossible for them to break that cycle with their child,” Jagannathan said. “When their kid is acting out, it’s not that they are consciously saying, ‘Oh, this kid is a problem, let me react harshly.’ Their reflex is ‘This stress is too high, and (how) I cope with these behaviors is problematic.'”

Jagannathan and Saeugling said people and systems frequently react to behaviors caused by trauma punitively instead of restoratively. Collective vision, skills and strategies, and resources are needed to intervene at every level of life. Their next steps are gaining input across agencies and institutions and figuring out how different sectors can connect to change the trajectories of people’s lives.

“It’s a solvable problem,” Saeugling said. “None of this is outside of our locus of control that makes it unsolvable.”

Both Jagannathan and Saeugling spent time living in the Bay area of California after teaching in eastern North Carolina through Teach for America. Through separate schooling and projects, they knew they wanted to return to what felt like home to both of them.

“There are, for better or for worse, a lot of communities in America that are similar to eastern North Carolina,” Jagannathan said. “I remain committed to proving that the reality for rural communities in America can be different. I feel like there’s an uncharacteristic amount of momentum around both east Tarboro and Edgecombe County and rural America that maybe we can capitalize on that.”

Meredith Capps, a project manager at Vidant Edgecombe Hospital, said that even if Hurricane Irma misses the region, she is worried about other storms throughout the next several weeks.

“We can’t handle but so much more rain,” Capps said. “And the scarier part is not even the first one that’s coming. It’s the possibility of two more coming in behind and we’re going to be saturated.”

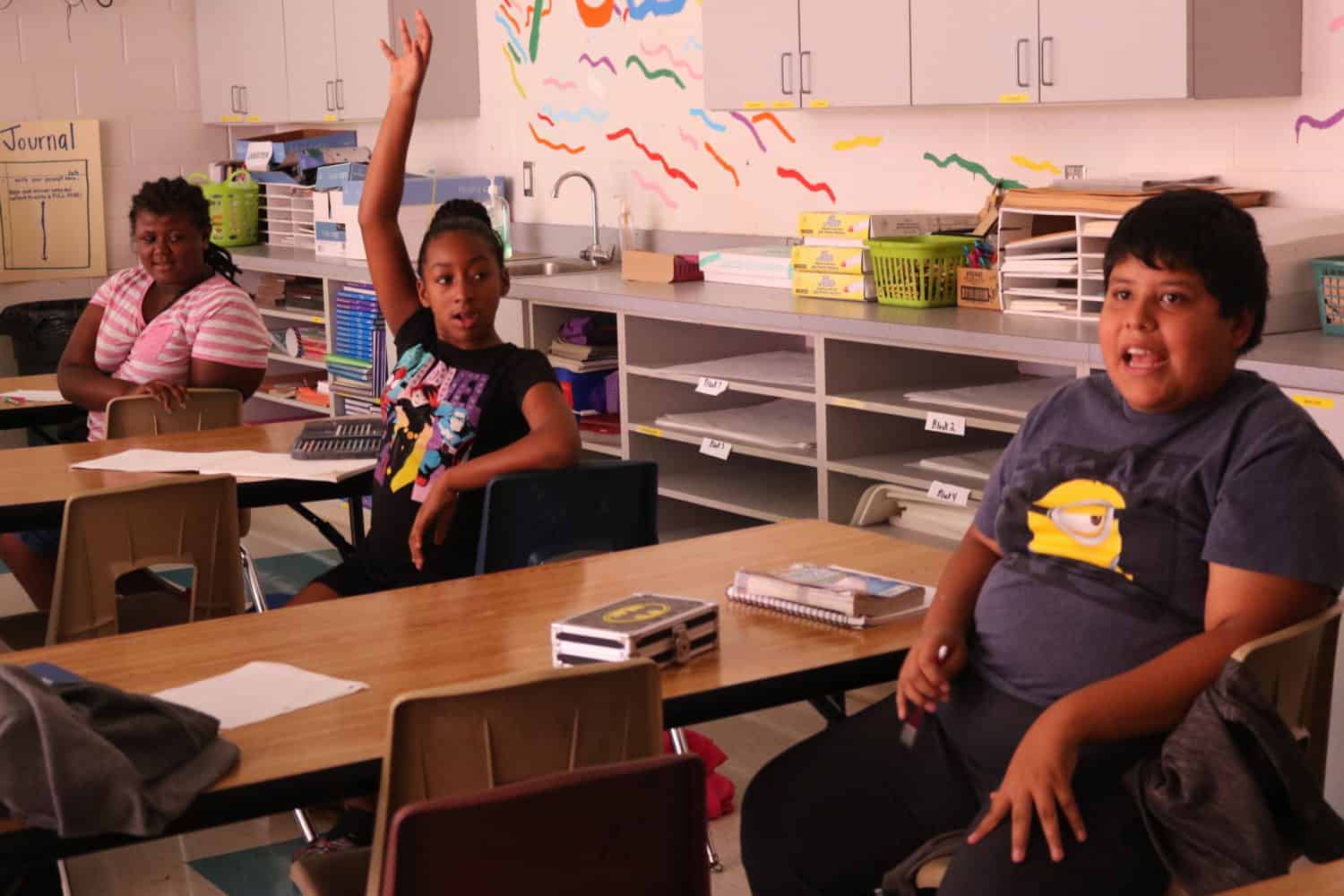

For now, Pattillo Middle School principal Lauren Lampron, who attended Thursday’s meeting, said she and her staff are focused on creating an environment where kids feel safe no matter the circumstances outside of school. Since Hurricane Matthew left over 80 percent of the school’s population displaced, the school has started focusing on trauma’s impact on students. Every morning, students have a home room where they learn about emotional literacy, school-appropriate behavior, team-building skills, and self-regulation techniques for anxiety, anger, or fear.

“It allows the student to be in that calm environment to start their day,” Lampron said.

Students complete surveys during the same period on how they feel and what is going on in their lives. A guidance counselor reviews the surveys. The potential storm was not something they wanted to bring up with the students, Lampron said, since the projections were not yet solid.

“We didn’t want to induce stress if it would end up turning,” Lampron said, “which it appears it now has.”